5.1 AMR and sex differences

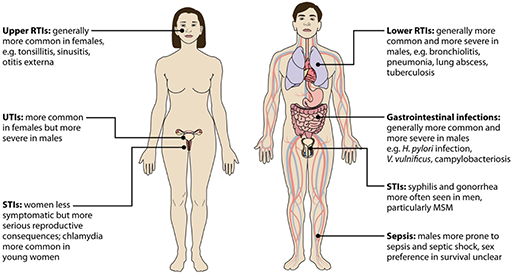

Sex – the biological differences between males, females and intersex people – can shape susceptibility to infection, including resistant infections (Figure 4). For example, females have a higher risk of developing UTIs because they have a shorter urethra, and UTIs have a high drug-resistance potential (Gautron et al., 2023). Risk of infection also increases around menstruation and pregnancy, which highlights how physiological changes over the life course have implications for exposure and vulnerability (Ghouri and Hollywood, 2020).

Biological or sex factors also interact with diverse social factors, including those that relate to gender:

- Healthcare settings can be sites of high exposure to resistant infections, and women often spend significant amounts of time there. This is in part due to sex-related factors such as childbirth but it is also because of common gender norms around women’s role as caregivers.

- Malnutrition can increase susceptibility to infection, including resistant infection. This is also gendered because in many contexts, families experiencing food insecurity may prioritise feeding boy children because of their economic roles.

- Poor water, sanitation and waste management can create conditions that drive the spread of infection, including resistant infections. Women and girls may be particularly affected by this because of the intersection of anatomical factors and their particular exposure to water-borne infections due to their role collecting water for the household (Gautron et al., 2023).

5 AMR, sex and gender