6 Revisiting the social and structural drivers of AMR

As you will have come to understand from your study in the course so far, AMR drivers are about not only antimicrobial practices but also social and structural determinants of health: the underlying societal and environmental factors that create conditions conducive to the development and spread of AMR.

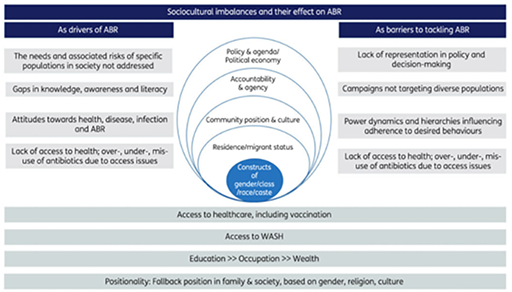

These are explained in Figure 5, which highlights how drivers of antibiotic resistance and barriers to managing antibiotic resistance are shaped by the socio-cultural inequities (such as gender inequity) that exist at multiple levels – from community to national and international. This includes stigma and social norms within communities, but also power structures within national health system structures and the lack of representation of communities and diverse groups in political decision-making. In this way, managing the spread of AMR needs to look beyond people’s knowledge and behaviours.

-

Think back to Table 2, which illustrates the challenges faced on the AMR people journey. Can you see how the sociocultural imbalances illustrated in Figure 5 map onto the AMR journey?

-

Things to consider here include:

- decision-making norms about access to healthcare, such as autonomy in decision-making

- access to education and knowledge about AMR

- the economic costs of diagnostic testing and the availability of diagnostic testing in countries.

Figure 5 highlights that AMR is not an issue of ‘misuse’, but rather of the structures that prevent recommended use. In fact, bans on antibiotic use are often offered as solutions to curb AMR. However, evidence from Mexico shows that these bans do not work, and people will find ways to work around them (Pérez-Cuevas et al., 2014). This is largely because in many contexts, there is an absence of holistic healthcare and antibiotics are seen as a ‘quick fix’ for the systemic disparities in power, resources and opportunities that result from institutionalised biases and practices (Willis and Chandler, 2019). Context, therefore, is critically important; this will be illustrated in the following case study on urban informal settlements.

5.2 AMR and gender differences