6.1 A case study on urban informal settlements

Urban informal settlements comprise a key structural inequity and have been described as hotspots for AMR (Nadimpalli et al., 2020). They are a clear case study of why structural inequities drive AMR.

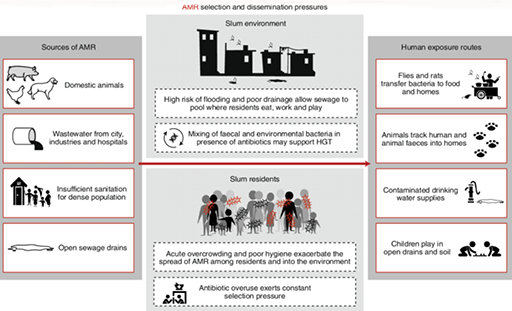

Informal settlements are often deemed to be ‘illegal’ because of an absence of formal governance, leading to poor environmental conditions, a lack of adequate healthcare and, subsequently, a proliferation of informal antibiotic use. Figure 6 illustrates how these conditions can facilitate the spread of AMR and constrain peoples’ abilities to access and use antimicrobials in the recommended ways.

Now complete Activity 6, which considers a case study of AMR in urban informal settlements.

Activity 6: A case study of AMR in urban informal settlements

Read the following case study on AMR in urban informal settings and watch the first five minutes of Video 3. Then answer the questions that follow.

Antibiotics as a quick fix for hygiene and inequality

Grace brings us into her house to show us her plastic basket of medicines she keeps on hand at home. It is a small collection of Panadol (paracetamol), some amoxicillin tablets and a full box of metronidazole. She explains that the metronidazole is an absolute necessity here in this urban informal settlement in downtown Kampala, Uganda, where chronic diarrhoea – and the serious abdominal pain associated with it – is a condition that many adults and children live with every day.

Walking through the settlement with her we pass the few existing fee-for-use latrines in the community, but Grace explains that most cannot afford them, and that regardless, many avoid them because they are so unclean. She explains that many people – including her – simply use home bucket systems or polythene bags for toileting, and then dispose of their waste either in the open drainage channels that run through the settlement or in community rubbish piles. These are the same drainage channels where people must wash their clothes and collect water for their livestock and gardens.

Further exacerbating this situation, the settlement is built on and beside a wetland area, and these drainage channels often flash-flood during the rainy season, with waters rising to knee-height and circulating inside people’s homes, their livestock pens and their small gardens. Here, antibiotics are put to use to make unavoidable diarrhoeal disease bearable, enabling people to carry on with their work and family commitments despite chronic diarrhoea and abdominal pain.

There is little political will to tackle these issues, as the local press describes the informal settlement as a problematic ‘slum’, while the people who live there are cast as ‘illegal squatters’ and criminals. Here, antibiotics provide a quick fix for wider structural and political issues, manifested as a lack of hygiene in contexts of poverty.

- In what ways do structural inequities drive AMR in informal settlements, or in a similar context that you might be familiar with?

- How are exposure and susceptibility shaped through the different types of environmental factors in urban informal settlements?

Discussion

Poor housing, water and sanitation systems lead to high levels of infections, including resistant infections. Poverty in informal settlements reduces people’s access to timely and equitable health services, meaning that people are more likely to need to access antimicrobials informally and use them regularly to address recurrent infections.

An intersectional approach helps to show how gender inequality and other overlapping factors like poverty or race amplify health risks faced by those living in informal settlements. Combining this with a One Health approach can highlight the intersections of human, animal and environmental health, and how these are inequitable.

6 Revisiting the social and structural drivers of AMR