Brighton Pavilion

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Wednesday, 1 May 2024, 10:25 PM

Brighton Pavilion

1 The Royal Pavilion

In this unit we shall be studying a quintessentially Romantic piece of architecture, the Royal Pavilion at Brighton, designed and redesigned over the course of some 30 years to the specifications of the Prince of Wales, afterwards Prince Regent and eventually King George IV (1762–1830; reigned 1820–30).

The Pavilion as we now know it in its final state was the result of a collaboration between the architect Sir John Nash (1752–1835), the firm of Crace (specialists in interior decoration) and their patron the Prince Regent. It makes a suggestive companion piece to the house of Sir John Soane.

Although both buildings are markedly personal in cast, Soane's house can be regarded as a Romantic ‘take’ on Enlightenment classicism, while the Pavilion could be called a Regency ‘take’ on the Romantic (what I mean by this distinction will become clearer as we progress). Whereas Soane's house celebrates the architect as sole creator, the Pavilion is much more typically the product of a collaboration between architect and client.

While Soane was and is the architect's architect, an intellectual and an academic, distinguished, original and serious, Nash was the darling of fashionable aristocratic society, careless, humorous and audacious in style, and was and is identified with the commercial and the opportunistic. Where Soane is essentially a purist, refining and romanticizing Neoclassicism, Nash is associated with eclecticism, which by contrast privileges asymmetry and recklessly mixes forms, motifs and details from different historical periods and styles.

The Pavilion itself has been called silly, charming, witty, light-hearted, extravagant, gloriously eccentric, decadent, childish, painfully vulgar, socially irresponsible, a piece of outrageous folly and a stylistic phantasmagoria. Whatever you decide about it, it has always been, beyond all dispute, an astonishing flight of the Romantic fancy, comparable in its impulse to Samuel Taylor Coleridge's famous poem ‘Kubla Khan’ (drafted 1798, published 1816, available to read in its entirety beneath the extract below. The poem begins:

In Xanadu did Kubla Khan

A stately pleasure-dome decree:

Where Alph, the sacred river, ran

Through caverns measureless to man

Down to a sunless sea.

Click on 'View document' to see Coleridge's poem 'Kubla Kahn' in its entirety.

Coleridge's poem did not in itself influence the building of the Pavilion, but both ‘Kubla Khan’ and the Pavilion do recognizably grow out of a common stock of Romantic ideas and feelings about the Orient. Here we shall be trying to come to some understanding of how, why and to what effect the prince's ‘pleasure-dome’ translated some of the modes and ideas of Romanticism into the language of architecture.

As we do so, we'll be thinking about the Pavilion as what we might call a ‘cultural formation’. By this I mean that considering the apparent eccentricity of this building can give us an insight into many aspects of Regency culture, and, conversely, that an enhanced knowledge of Regency culture can help us to decode the meanings of the building for its own time.

The Pavilion can be seen as the physical realization of the coming together of many aspects of Regency society: systems of patronage of the arts; ideas of health, leisure and pleasure; notions of technological progress, which drove the Industrial Revolution and were in turn reinforced by it; concepts of public and private and the proper relations between them; ideas of royal authority in the post-Napoleonic era of restoration of hereditary monarchies across Europe; the fashion for Oriental scholarship and the ‘Oriental tale’; and powerfully interconnected ideas of trade, empire and the East. By the end of the unit, therefore, you will, I hope, have developed a sense of some of the (sometimes contradictory) values dramatized by Romantic exoticism.

Before we can talk about the meanings of the Pavilion in its own time, however, you will need to familiarize yourself with the building. On the video clips (below), The Royal Pavilion, Brighton, you will find a virtual tour of the Pavilion, inside and out. The video is structured as though you were a visitor to the Pavilion in the early 1820s. You will trace the route through the rooms that you would have followed if you were arriving as a guest at one of the prince's famous evening receptions, consisting of dinner followed by music. You will hear on the sound-track the music that the prince loved, together with some of the comments of his guests, and extracts from contemporary descriptions of the Pavilion's interior from a newspaper and a guidebook.

Exercise 1

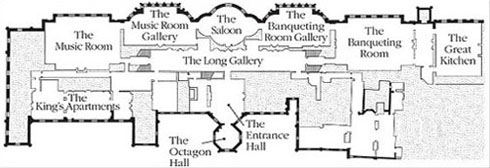

Read the accompanying AV Notes (below) and then watch all three video clips carefully once through. Concentrate principally on the look of the exterior and of the interiors. Then I suggest you watch the videos again, following your route on the modern ground-floor plan provided below (Figure 1), and looking carefully at the contemporary watercolours of exteriors and interiors provided below (Plates 1–11).

Once you have done this, compile a list of adjectives that occur to you to describe your experience of the building, both exterior and interior. You might also like to add to your list some phrases describing those effects in which this building is conspicuously not interested.

Click on 'View document' to see plates 1-11, watercolours depicting the interior and exterior of the pavilion.

Click on 'View document' to read the AV notes for the video below.

Click below to view clip 1 of the video.

Click below to view clip 2 of the video.

Click below to view clip 3 of the video.

Figure 1

Discussion

I don't expect that our lists will match exactly – but we might agree roughly on some of the effects that the building produces on us. What I've noted down is that the exterior strikes me as definitely ‘Indian’ – in fact, vaguely reminiscent of the Taj Mahal. The Entrance Hall, the Long Gallery and the Saloon are clearly ‘Chinese’, and so are the Banqueting Room and Music Room, although they are Chinese (with a dash of ‘Indian’?) in a rather different and much more grandiose mode. (Don't worry if you found it hard to put your finger on the exact difference in style; we'll be unpicking these Indian and Chinese effects in more detail a little later.)

After that, I have a list of descriptive terms that runs something like this: conspicuously expensive; sumptuously detailed to the suffocating edge of over-kill; self-advertising; highly personal, fantastic and esoterically refined; spectacular, theatrical and faintly reminiscent of some of the pleasures of Disneyland's evocations of foreign parts; sensual to the point of overwhelming the senses; and, related to this, disorientating (all those mirrors and all that trompe l'oeil); an escapist pocket palace.

As for what this building is not trying to do or be – it is spectacularly not invested in neoclassical politeness, nor in antiquities or other sorts of collectables. The Pavilion is profoundly uninterested in the past, the nation or conventional domesticity, in respectability, or in social responsibility, or in work of any sort. Related to this last point, it is conspicuously not the centrepiece of landed wealth – it is not standing in a place of eminence, embedded within its own estate and associated farms which would be visibly providing the income for the upkeep of the house. Carrying this thought a little further suggests forcibly that the wealth this palace is designed to display is a wealth of taste and imagination. Above all, this building is surprising.

Actually, I'd go further than this – I think this building is astonishing, and its sheer improbability generates in me a curiosity about the circumstances that could conceivably have made it possible.

Exercise 2

Now I want you to try to formulate a set of questions that the Pavilion might prompt about the culture that produced it. To this set of questions, I should like you to add a list of the sorts of information you would need to collect about that culture so as to be able to answer them. (If you are feeling especially imaginative and adventurous, you might like to write yet another list of suggestions as to where you might start looking for this sort of information.)

Discussion

My list of initial questions looks like this (again, it won't match yours exactly or perhaps even at all, and you shouldn't worry about that):

Why was the Prince of Wales building a palace in Brighton at all?

For what was the Pavilion intended and used, and for how long?

When and why did he choose this style of exotic architecture and interior decor?

Why is the Pavilion ‘Chinese’ on the inside but ‘Indian’ on the outside?

What did everyone think about it at the time?

My second list, of information I would need to collect so as to begin to answer these questions, runs as follows:

Find out about the Prince of Wales – e.g. his other residences, his relations with his father's court in London, where his money was coming from, and where he got the idea for the Pavilion (try biographies, books on court history).

Find out about Brighton and why it had become fashionable at this juncture – at a guess, it must have been fashionable for the prince to have ended up there (start with histories of Brighton, and eighteenth- century, early nineteenth-century and modern guidebooks to the city).

Find out something about the history of the building of the Pavilion (again, try guidebooks old and new and see what leads come up; also see whether rival architects published sketches and ground-plans to support their bids for the work).

Find out whether there were any earlier or other contemporary buildings that were ‘exotic’ in this style. Perhaps there were architects/interior designers who specialized in this sort of work? Possibly as part of a long tradition in such designs? Or was this style a fashion that was echoed across the period in, say, literature and painting? (Try books about architecture, or studies of the Romantic exotic more generally.)

Find out who were the prince's visitors to the Pavilion, and see if they wrote letters or diaries describing their visits. The same might apply for prominent writers who were visitors to Brighton. Check, too, for political caricatures of the prince that might comment on his building of the Pavilion.

What I've just done, as you can see, is to write out a rough programme for research. In fact I followed this programme in order to write what follows, and I hope you will enjoy following me step by step through what I discovered – and deciding whether you agree with my judgements.

This unit is an adapted extract from the Open University course From Enlightenment to Romanticism c.1780-1830 (A207).

2 A prince at the seaside

In this section we will take a closer look at the life of George IV and what brought him to Brighton.

The Prince of Wales (see Figure 2 ), known familiarly to his friends as ‘Prinny’, was born in 1762 and destined to become Prince Regent in 1811 following the onset of the madness of his father, George III. He finally became George IV in 1820, but reigned as such for only a decade, dying in 1830 at the age of 68. He is remembered as a great connoisseur and collector of art (setting a precedent for subsequent Princes of Wales to take an interest in architecture), most especially through his patronage of John Nash, who at his behest redesigned Buckingham Palace and created the elegant London developments still known as Regent Street and Regent's Park. Handsome, intelligent and accomplished, the prince was also highly emotional, duplicitous, painfully susceptible to flattery, wildly extravagant, greedy for excitement and personally theatrical. The Princess Lieven, wife of Tsar Alexander I's ambassador and a notable judge of character, described him as he was in the 1820s, as having ‘some wit, and great penetration’:

he quickly summed up persons and things; he was educated and had much tact, easy, animated and varied conversation, not at all pedantic. He adorned the subjects he touched, he knew how to listen, he was very polished … also affectionate, sympathetic, and galant. But he was full of vanity, and could be flattered at will. Weary of all the joys of life, having only taste, not one true sentiment, he was hardly susceptible to attachment, and never I believe sincerely inspired anybody with it.

(Temperley, 1930, p.119)

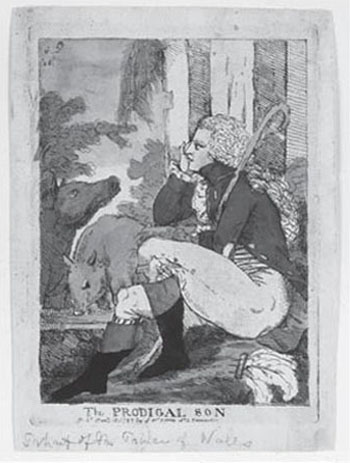

In early life the prince was also breathtakingly indiscreet, both in his youthful politics (he was a hard-core oppositional Whig rather than favouring the establishment party, the Tories, supported by his father) and in his youthful love affairs (which were many and various, culminating in the scandal of his private, unacknowledged, unconstitutional and therefore unlawful marriage to the Roman Catholic widow, Mrs Fitzherbert). As a result, and as so many heirs to the throne have done, during his twenties and thirties the prince enjoyed a strained relation with his father's court, which he found staid and stifling. His form of rebellion was to combine spendthrift dissoluteness (hence the anonymous print of 1787 depicting the prince as the Prodigal Son; see Figure 3 ) with the life of an aesthete, which found expression in the court he held at Carlton House. His set of associates included dandies such as Beau Brummell (who affected beautiful, consciously urban clothes and a pose of bored languor as he strolled up and down the Mall), sporting rakes like the Duke of Queensberry, and high-class courtesans such as Harriette Wilson. These were blended with society literati such as the playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan, the millionaire connoisseur William Beckford (author of the torrid Oriental fiction Vathek: An Arabian Tale (1786), who purchased the famous statue of Napoleon pulled down from the Vendome Column, and the best-selling poet Thomas Moore, shot to fame by the success of his long Oriental romance poem Lalla Rookh (1817).

Figure 2

Figure 3

Carlton House, sumptuously decorated in the height of fashionable Francophile taste in line with the prince's Whig sympathies by the important architect Henry Holland (1745–1806), was the setting for a series of the extravagant parties which the prince so loved to give, culminating in the famous Carlton House fete in 1811 on his appointment as Regent. The dazzled Thomas Moore wrote to his mother about this fete, detailing the delights of the indoor fountain and the artificial brook that ran down the centre of the table, and concluding, ‘Nothing was ever half so magnificent. It was in reality all that they try to imitate in the gorgeous scenery of the theatre’ (quoted in Hibbert, 1973, p.371). Byron's friend and fellow radical poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, by contrast, was predictably outraged by the cost (see Hibbert, 1973, p.374). In the event Carlton House, with its rival court, did not prove far enough removed from his father to suit the young heir. Instead he would lure his raffish and brilliant society, with its love of extravagance and theatricality, out of the capital and down to the margins of the nation, to a place then called Brighthelmstone, some eight hours away by stage-coach (although in 1784 the prince achieved the journey in four and a half hours for a bet).

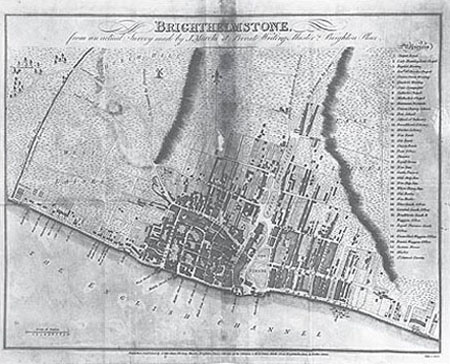

The Prince of Wales first visited Brighton (short for Brighthelmstone) in 1783, aged 21, staying with his uncle at Grove House on the Steine (or Steyne), a broad street that led from the seafront into the heart of town (see Figure 4 ). He was prompted partly by his ever-lively desire to escape the disapproving eyes of his father's court, and partly by the recommendation of his physicians, who suggested that sea water might ease the glandular swellings in his neck. This sea-water cure had been the original cause of the rise in the popularity of Brighton as a watering place, which had started around 1765, courtesy of a Dr Richard Russell of Lewes who had publicized the health-giving properties of bathing in, and drinking, sea water in his A Dissertation: Concerning the Use of Sea Water in Diseases of the Glands, etc . (1752). Sea water taken one way or another, according to Russell, would cure almost any disease, including ‘fluxions of redundant humours’, rheumatism, madness, consumption, impotence, rabies and childish ailments. Among the early visitors was Dr Johnson, but it was soon to become a resort for the fashionable as well. As one wag was to put it, high society ‘Rush'd coastward to be cur'd like tongues/By dipping into brine’ (unattributed, quoted in Roberts, 1939, p.3), or turned out to spy through telescopes on ‘mad Naiads in flannel smocks’ as they emerged briefly from their bathing machines (Pasquin, 1796, p.5).

Figure 4

Click below to view a larger version of the Map of Brighthelmstone.

These health treatments, generally undertaken after the rigours of the London season which ran from March until June, were much sweetened by the other pleasures that Brighton had on offer besides the beauties of nature. They included a racecourse, hunting, circulating libraries, promenading and ogling along the Parade, donkey-rides on the beach, balls and assemblies at the Old Ship and the Castle Inn, and the theatre, where you might have seen the celebrated actresses Mrs Siddons and Mrs Jordan. (The new Theatre Royal at Brighton was soon able to attract such London celebrity performers not just during the summer, when the London theatres were closed, but over the Christmas season too.) This landscape came complete with figures – rakes, parvenus, the frail lovelies of the so-called ‘Cyprian corps’ (a Regency euphemism for prostitutes, derived ultimately from the classical myth that Venus was born naked from the waves at Cyprus) and officers from the nearby military camp. The army came under the prince's personal command in his capacity as commander-in-chief, and many officers were his intimates; the arrival of the military therefore sealed the glamorous image of the resort. As Jane Austen was to write in Pride and Prejudice (1813):

In Lydia's imagination a visit to Brighton comprized every possibility of earthly happiness. She saw with the creative eye of fancy, the streets of that gay bathing-place covered with officers. She saw herself the object of attention to tens and scores of them at present unknown … she saw herself seated beneath a tent, tenderly flirting with at least six officers at once.

(Austen, 1967, p.232)

This invasion of London raffishness prompted the occasional fierce satire. Anthony Pasquin's poetic The New Brighton Guide (1796) describes Brighton in a note as

one of those numerous watering-places which beskirt this polluted island, and operate as apologies for idleness, sensuality, and nearly all the ramifications of social imposture … where the voluptuary [seeks] to wash the cobwebs from the interstices of his flaccid anatomy.

(Pasquin, 1796, p.5)

The painter Constable sourly described Brighton as ‘Piccadilly or worse by the sea’ and ‘the receptacle of the fashion and off-scouring of London’ (quoted in Leslie, 1951, p.123). But the prevailing view of Brighton was that, unlike more established resorts, it offered a picturesque, even a virtuously Rousseauesque, rustic informality, allowing visitors to escape the constrictions and excesses of life in town to partake of ‘pure air, rational amusement, and sea-bathing’ (Fisher, 1800, p.viii). As Mary Lloyd put it in her Brighton: A Poem,

it was a pleasing gay Retreat,

Beauty, and fashion's ever favourite seat:

Where splendour lays its cumbrous pomps aside,

Content in softer, simpler paths to glide.

This agreeable vision owed a good deal to the Prince of Wales himself, who both set the seal of fashionability upon Brighton (relegating its rivals, Bath and Tunbridge Wells, to middle-class dowdiness) and did much to exploit and reinforce this cult of Romantic love-in-a-cottage – to begin with, at least. Having rented a picturesque farmhouse on the Steine in 1784 for a couple of years, he determined in 1786 to reform, retrench and retire to Brighton, installing his new wife Mrs Fitzherbert just around the corner, there to live a life of simple, if self-dramatizing, poverty (see Figure 5 ). Strict economy notwithstanding, he commissioned his then favourite architect Henry Holland to convert the farmhouse into a gentleman's residence with good views of the sea and the Steine. Rebuilt in the early summer of 1787, it would come to be called the Marine Pavilion.

Figure 5

Exercise 3

Look carefully at the two prints which show the Marine Pavilion in 1787 and 1796 (Figure 6 and Plate 12 ), at the ground-floor plan of Holland's Marine Pavilion (Figure 7), and at the watercolour which shows the interior decorative scheme of the Saloon c.1789 (Plate 13). I should like you to make some notes along the following lines:

Describe some of the architectural features (both exterior and interior) that strike you.

Make a stab at identifying the architectural styles that this building evokes.

Consider the house's relation to its setting.

Consider what your observations might tell you about the young prince's vision of his life in Brighton.

Speculate on what the prince may have been intending to suggest by calling his newly modelled house a ‘pavilion’. (Here you might find it illuminating to consult the Oxford English Dictionary.

Click below to view the four images refered to in the exercise.

Discussion

Holland's Marine Pavilion is notably symmetrical in conception. The original farmhouse has vanished into the left-hand wing of the new structure, which is now mirrored by an identical right-hand wing with matching bays. The composition is centred on a domed rotunda fronted by slender Ionic columns. The building is whitish, unlike the surrounding brick buildings. The same symmetry is visible in Thomas Rowlandson's depiction of the interior of the Pavilion ( Plate 13 ). Mirror is balanced by mirror, seat by seat and fireplace by console. The plasterwork is uniform, and repeated in panel after panel and in the coffering of the ceiling.

The rotunda (and its columns) make clear reference to classical civilization. It is Roman in its evocation of the Pantheon and Greek in its Ionic columns. This Neoclassicism is further underlined by Holland's decision to clad the whole building in cream-glazed Hampshire tiles, mimicking the paleness of marble. The symmetry visible in the interior of the rotunda is similarly neoclassical. This scheme is also derived – via the interior designer Robert Adam (1728–92) – from the coffered interior of the Pantheon.

The Pavilion is orientated very strongly towards the main street on which it is located (the Steine) and therefore to taking part in the social display that was such a feature of this area. The house combines both modesty and grandeur: it is almost aggressively modest in height in relation to the other buildings around it, but at the same time it makes no effort to blend in with them.

The building suggests that the prince saw himself while sojourning in Brighton as passing incognito, disguised as a commoner. But at the same time it also suggests that the prince's disguise was meant to be penetrated; he might have been living in virtuous poverty, but this was poverty in the most sophisticated taste, poverty as fashion statement, poverty as a holiday from inborn and inalienable royal importance.

There is much to be deduced from a name. By calling his house a ‘pavilion’ – a term, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, which at this period (the 1780s) meant exclusively an Oriental tent, a temporary and moveable outdoor dwelling – the prince was invoking a striking series of connotations: of temporariness, of holiday and of fantasy escape. (In fact, the rotunda does have something of the appearance of a tent-like structure, and the architect Humphrey Repton (1752–1810) compared the interior effect to that of a marquee (see Dinkel, 1983, p.20).)

On the one hand, then, this building is thoroughly conventional. This sort of neoclassical architecture was an eighteenth-century Enlightenment shorthand for belonging to a well-heeled, cosmopolitan Whig landowner. The whole – dignified, sumptuous, but quite subdued in effect – is depicted by Thomas Rowlandson as populated with figures engaged in the polite and formalized conversation of good society (see Plate 13 ). On the other hand, the prince's retreat was founded in a fantasy of ‘dropping out’. The restless owner would not long remain content with this version of his Pavilion; but at its core through all its transformations lay a notion of self-dramatizing metamorphosis and of temporary, alternative and essentially irresponsible experience undertaken incognito. (An incident from the prince's early life is particularly telling here; in his twenties he fell for the beautiful actress Mary Robinson in the role of Perdita in Shakespeare's late romance The Winter's Tale. Perdita is apparently a shepherdess but is actually a lost princess; she meets and falls in love with Florizel, seemingly a shepherd but in fact a prince in disguise. Not for nothing were the couple promptly dubbed by London society and by the caricaturists ‘Florizel and Perdita’ – the prince clearly loved romantic slumming from very early on.)

3 From Enlightenment to Romantic?

In 1800, having divorced Mrs Fitzherbert and contracted a disastrous marriage with Princess Caroline of Brunswick, forced on him by the necessity of persuading the king to clear his vast debts, the Prince of Wales fled back to Brighton with his court. In 1801 he whiled away his time (and squandered Caroline's dowry) dreaming up extensions and changes to the interior decor of the Pavilion.

Of these, certainly the most interesting and prophetic was his development of the interior into a Chinese fantasy between 1802 and 1804, a development perhaps suggested by his fantasy of a ‘pavilion’ – a term that by now was being applied to small garden buildings of a Chinese style. He hung his newly decorated rooms with genuine Chinese wallpaper sent from that country's imperial court and crammed them with a collection of imported items supplied by the firm of Frederick Crace & Sons. These ranged in promiscuous profusion from model pagodas and carved ivory junks to birds’ nests, Chinese razors, silks and pieces of fine porcelain. Like Soane, he seems to have been taken with the idea of displaying a collection of curiosities, mounting the rare and the bizarre in witty and deliberately heterogeneous juxtaposition. Lady Bessborough wrote of the effect in 1805: ‘I did not think the strange Chinese shapes and columns could have looked so well. It is like Concetti in Poetry, in outre and false taste, but for the kind of thing as perfect as it can be’.

By ‘Concetti’ Lady Bessborough meant the elaborate ‘conceits’ (strained and conspicuously witty metaphors that yoke unlikely things together) of the sort characteristic of the lyrics of the seventeenth-century English poet John Donne.

It is important to understand, however, that the prince's liking for things Chinese was not especially innovative. The rage for Chinese imports had gone in and out of fashion throughout the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries as French and British traders had penetrated the huge Chinese empire. The rich and aristocratic, leaders of fashion, had typically amassed rare and beautiful objects from the Chinese export market, most especially porcelain and silks, which embodied superior technological skills that to date had baffled the West. So important did Europe become as a market for these wares that the Chinese invented a special export market, designing on vases and bowls painted scenes purportedly of European life but in a distinctively Chinese style. This English liking for Chinese products spilled over into a variant of Rococo style around the 1740s. Known as chinoiserie, this influenced the design of textiles, furniture and gardens in courts and great houses across Europe, including one belonging to the Russian empress, Catherine the Great (1729–96). The 1780s and 1790s saw in particular a fad for Chinese gardening in a ‘ grotesque ’ style. This resulted in the famous pagoda designed by Sir William Chambers (1726–92) for London's Kew Gardens, in Frederick the Great's Chinese-style tea-house at Sans-Souci in Germany, and in the similar Chinese tea-house in the grounds at Stowe in Buckinghamshire, all of which can still be seen if you care to visit them. Like the pleasures of the Gothick folly (exemplified in the building of Fonthill Abbey in Wiltshire by the prince's vastly rich friend, William Beckford), this sort of ‘Chineseness’ bore witness to a rebellious undercurrent that ran counter to, and in parallel with, established Neoclassicism, although for the most part safely located outside the house in the grounds. As John Dinkel puts it:

Those essentially ornamental eye-stoppers, the innumerable sham Gothic ruins, pyramids, Turkish tents, pagodas, and Chinese teahouses that sprinkled gentlemen's estates, were all fashionable expressions of the impulse to break the established rules of classical taste.

(Dinkel, 1983, p.7)

Yet escaping into Chinese fantasy was, to the eighteenth-century mind, not an escape into the barbaric. The Chinese appeared to an Enlightenment eye to offer an alluring model of imperial stability, of gracious ritual and strict hierarchy, of wit, charming illusion, and the pleasures of narratives in miniature. The Chinese were supposed to be eminently civilized. This was one reason why Oliver Goldsmith's novel satirizing the follies of British society, The Citizen of the World (1762), took as its central figure a Chinese philosophic gentleman residing in London writing home in some bewilderment at the habits of the natives, and why Voltaire took the view that China was a sophisticated land of admirable stability peopled by philosophes. The connotations of China in the prince's day were, in short, those of luxury, gaiety and the trappings of rank (Dinkel, 1983, p.33), although increasingly towards the end of the eighteenth century this view was tempered by a sense that Chinese civilization was stagnant by comparison with the vigour of Enlightenment Europe.

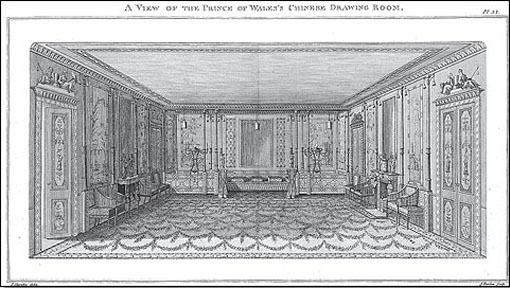

The prince himself was not new to the pleasures of connoisseurship in this area; by 1790 Carlton House already boasted the famous Yellow Drawing Room in the Chinese style (see Figure 8 ). At this time, Chinese taste was all the rage in ‘advanced’ circles. None the less, it was one thing to collect the occasional piece of beautiful china and the odd strip of hand-painted wallpaper, setting them in ‘exotic’ colour schemes, and quite another to collect pagodas, birds’ nests, razors and vast amounts of china. The one was an exercise in graceful allusion, the other a demonstration of a witty taste for the grotesque and the bizarre, increasingly characteristic of turn-of-the-century Romantic taste.

Figure 8

Click below to a larger version of A View of the Prince of Wales's Chinese Drawing Room.

Exercise 4

I'd like you to look carefully at Figure 8 and compare it with:

Rowlandson's sketch of the original interior of the Saloon in the Marine Pavilion (Plate 13) and;

the illustration of the Long Gallery, which shows a rather later decorating scheme designed by Frederick Crace around 1815 (Plate 5).

What, if anything, does the Yellow Drawing Room have in common with each of these schemes?

Click on 'View document' to see plate 13, interior decorative scheme of the Saloon.

Click on 'View document' to see plate 5, illustration of the Long Gallery.

Discussion

Clearly, all three designs do have in common an underlying concern with symmetry and balance, a thoroughly neoclassical and Enlightenment trait. But my own sense is that the Chineseness of the Yellow Drawing Room is more akin to the spirit of the sketch of the Saloon. It speaks of a cultivated taste, backed by plenty of money and leisure; it is decorative and witty, polite and, most important, formal, as befits a royal London residence. (The Saloon seems a little less formal in Rowlandson's conception – but then, it is part of a holiday house in a seaside resort.) By contrast, Crace's designs for the Long Gallery seem much more invested in alternative, exotic experience, perhaps straying outside the strictly polite. You may have noticed how the underlying neoclassical symmetries of the Long Gallery are broken, distorted and unsettled by the quite violent diagonals of the bamboo on the wallpaper, by the tiles that line the coving, mimicking a Chinese roof, and especially by the consciously ‘foreign’ lines of the cast-iron dragon columns that stand at each side of the passage. The colours are brilliant, and flamboyantly and unconventionally combined. The effect is akin to the idea of the picturesque: it privileges a roughness, a serpentine line, ‘variety’ and the power of a framed perspective. It is a theatrical experience – which perhaps is not so very surprising given that the Long Gallery (unlike the Saloon) was for looking down and walking through rather than sitting in.

What the differences between these interior schemes suggest to me is that by 1815 the prince's earlier ‘Enlightenment’ taste for chinoiserie had metamorphosed into something more ‘Romantic’, something less congruent with neoclassical order, balance and symmetry. That slight but definite tinge of the bizarre suggested by the collection of birds’ nests in 1802 would be much elaborated by the prince and his designers over the first two decades of the nineteenth century.

At the turn of the century, the governing idea of a ‘man of taste’ was changing. Whereas during the eighteenth century such a man would have been concerned to display his genealogy, his wealth and his classical education topped off with Grand Tour souvenirs in his house, he now invented himself by creating something strange and personal; hence the fantasy-world interiors of Beckford and Soane, ‘hungry for thrilling sensations evoked by ancient and Eastern artefacts’ (Dinkel, 1983, p.8). This intensely personal and sensational fantasy would become a hallmark of Regency, and Romantic, style. Dandyism in taste, and the ascendancy of the most famous dandy of them all, Beau Brummell, for several years the prince's boon-companion, was only just around the corner. The Pavilion's Chinese interiors, therefore, were to the prince an expression of Romantic subjectivity, a crystallization of his sense, shared by many contemporaries (including, for example, Soane), that he was a uniquely sensitive and involuted soul. As he was to write in 1808 to Isabella Pigot, Mrs Fitzherbert's companion:

I am a different Animal from any other in the whole Creation … my feelings, my dispositions, … everything that is me, is in all respects different … to any other Being … that either is now … or in all probability that ever will exist in the whole Universe.

(Quoted in Dinkel, 1983, p.9)

But although the prince's Chinese interiors clearly satisfied his desire for distinctiveness, the Chinese style was conspicuously unfashionable by comparison with the rage for the Egyptian or the Greek (mostly inspired by Nelson's victorious Nile campaign and the researches of Napoleon's invading archaeologists), or even the picturesque Gothic.

The Chinese was, frankly, vulgar at this juncture, associated with London's famous public pleasure-grounds, Vauxhall and Ranelagh. Although it promptly came back into fashion, that was because the prince had espoused it. Two explanations for this surprising choice can be advanced. One is personal: that the style satisfied George's nostalgia for ‘the forbidden masquerades and the festive amusements of his youth’ (Dinkel, 1983, p.30).

The other possible explanation is that the dream of enlightened despotism and secure hierarchy so encoded in eighteenth-century aristocratic views of the Chinese may have been peculiarly congenial to a prince now leaning towards Toryism in the troubled aftermath of the French Revolution. At the exact moment, then, that Napoleon was playing with images of authority in his efforts to invent himself as emperor, the prince was also playing with representations of his power.

A sharpened nostalgia for the endangered and perilous splendours of absolute monarchy could be played with and played out in games of defiantly extravagant style, sourced from accounts of Lord Macartney's embassy to the Emperor Ch'ien Lung in 1792, lavishly illustrated by William Alexander.

The effect seems, however, to have been ambiguous if we are to believe one of the prince's slightly puzzled visitors: ‘All is Chinese, quite overloaded with china of all sorts and of all possible forms … the effect is more like a china shop baroquement arranged than the abode of a Prince’ (Lewis, 1865, vol.II, p.490).

‘Baroquement’ signifies ‘in a Baroque fashion’: the commentator means that the china is piled up in an elaborate, ornate and rather overpowering arrangement, very different from neoclassical simplicity, symmetry or elegance.

In the next section we'll look in more detail at how the illusion of Chineseness is created in these interiors, and at the evolution of the prince's Chinese interiors from Enlightenment chinoiserie to a full-blown, stage-set, Romantic version of the East.

4 ‘Chinese’ on the inside

Our evidence for the evolution of the Pavilion's interiors is largely derived from Augustus Pugin's watercolours of the building's interiors and exteriors, executed for a picture-book commissioned around 1820 by the house-proud prince from his architect John Nash, entitled Views of the Royal Pavilion, completed in 1826. On the whole, the Pavilion today has been restored to congruence with the Views, to appear as it did in 1823 when the building was finished. Let's now look at the Pavilion room by room, starting with the Octagon Hall, the Entrance Hall and the Long Gallery.

Exercise 5

Return to the video viewed at the start of this unit and to plates 3-5 (below) and take a careful look at the details of these three rooms. I'd like you to make notes in answer to the following questions:

What elements of the decoration are specifically Chinese?

What other elements of the decoration suggest fantasy architecture?

Click on 'View document' to see plates 3-5.

Click below to view clip 2 of the video, which features the Octagon Hall, the Entrance Hall and the Long Gallery.

Discussion

The Octagon Hall. Fashionably restrained in its colour scheme, this octagonal room none the less boasts two Chinese features – the little bells hanging from the ceiling and the central pendant lantern. Less specific is the elaborate reticulation of the cove and ceiling, gently suggesting a tent-like structure, a garden pleasure-pavilion.

The Entrance Hall. Chineseness is suggested most strongly by the dragons painted on the back-lit clerestory windows (which are, incidentally, echoed by dragons painted discreetly on the panels) and the lanterns at each corner. But, again, this is a restrained room in terms of its colour scheme, and it is strongly neoclassical in its insistence on certain symmetries, most notably in its provision of a false door to match the real door beside the fireplace.

The Long Gallery. In contrast to the preceding rooms, which suggest a style without setting definite expectations, the Long Gallery establishes without equivocation the Chinese theme that will be played out in so many different varieties of scale and feeling elsewhere in the building (Dinkel, 1983, p.78). Chinese features you might have picked out include the hexagonal lanterns, the silk tassels, the motif of bamboo and birds on the wallpaper, the bells lining the cornice, the Chinese figures and porcelain, the dragons and the Chinese god of thunder painted on the skylight, and the faux bamboo trellises projecting from the walls and ceiling and forming the banister and rails of the cast-iron staircase leading to the first floor. More nebulously, the colour scheme and the level of decoration are emphatically not neoclassical: the effect is of a riot of daringly clashing colours (pink, blue and scarlet, for example) and intricate geometric multicoloured decoration.

Much less Chinese, but certainly conducing to a fantasy effect, is the startling multiplication of cleverly placed mirrors in enfilade to produce a series of special effects. At four points along the corridor large opposing glasses create transverse vistas; in each recess a mirrored niche reflects a tall china pagoda where the lines of sight from one of the drawing rooms and from the corridor meet; and at the ends, where the corridor leads into the Music and Banqueting Rooms, double-doors entirely faced in mirror glass give a perspective of infinite repetition (Dinkel, 1983, p.81). (Contemporaries invariably remarked on the dazzling effect of the mirrors, and further evidence for the effect of the enfiladed mirrors in the Long Gallery is provided indirectly by the account of Soane's use of such mirrors in his country house, Pitzhanger Manor: he too thought they gave ‘magical effects’, but one of his guests did indeed mistake them for a corridor and was injured so badly that Soane felt obliged to have some of them removed to reduce the illusion – see Batey, 1995, p.23.)

One feature by which you may have been puzzled is the decoration along the cornice in the Entrance Hall, and indeed in the Banqueting Room Gallery, which is related (in miniature) to fan-vaulting. This owes more to the other contemporary fantasy style of Gothick than to those associated with the East. Put very briefly, Gothick simply sought to evoke (not very conscientiously) medieval church architecture, pretty much that of the so-called Perpendicular period of the first half of the fourteenth century. Strawberry Hill Gothick, so named after the home of Horace Walpole (1717–97), is especially lacy and fanciful, as you can see from the example in Figure 9.

So far, then, our tour of the Pavilion has identified three styles in use: the neoclassical (which dictates the symmetries of the rooms and their arrangements), the Gothick (which surfaces from time to time) and the Chinese. As we move into the main rooms, however, you should notice another set of references creeping in. We'll start by exploring the rest of the Pavilion, walking into the Music Room Gallery, the Saloon and the Banqueting Room, all originally used as drawing rooms – that is to say, the rooms to which the ladies withdrew to leave the men to drink their port, for coffee and liqueurs, for playing cards after dinner, and for occasional dancing, small concerts and recitals.

Exercise 6

Return to clip 3 of the video and continue your virtual tour concentrating on the Music Room Gallery, the Saloon and the Banqueting Room Gallery. By now your eye will be familiar, I hope, with the neoclassical, the Gothick and the Chinese, and you will have noted, for example, the Chinese fretwork, the neoclassical scheme of white and gilding characteristic of earlier interiors by the celebrated architect Robert Adam, and the cornice of tiny Gothick fan vaults. What other influence or influences might be at play here? (Clue: the decorative features that interest me here are principally the pillars in the Music and Banqueting Room Galleries and the tops of the mirrors in the Saloon.)

Click below to view clip 3 of the video.

Discussion

The pillars in the Banqueting Room Gallery are unmistakably meant to look like palm trees (which did not carry Chinese associations), and although the tops of the pillars in the Music Room Gallery look like the sort of Chinese umbrellas carried over high officials in imperial China, snakes rather than dragons curl round the columns. In the Saloon, the tops of the mirrors are unmistakably Mogul-inspired in their swelling forms. The mantelpiece and door-frames boast more snakes. There is, in short, a whiff of India about these three rooms, blended with the Chinese fantasy. (If you are especially sharp-eyed, you might also have noticed a faint flavour of the Egyptian in the furniture, especially in the shape of the river-boat couch with crocodile feet.)

Figure 9

The Saloon is, of course, where we started looking at the neoclassical Adamesque scheme portrayed in Rowlandson's sketch of c.1789; it is the inside of Holland's rotunda. By 1815 it had metamorphosed, courtesy of Crace, into a Chinese fantasy of a garden arbour, complete with a colourful trellis cornice hung with pendants, panels of Chinese wallpaper and Chinese lanterns. In 1823 Robert Jones swept all of this away in favour of sumptuous crimson, white and gold with an Indian edge. (In its present state it is not quite restored to the Jones scheme, so you should glance again at Plate 9 In evoking India, the Saloon spoke of empires, both Mogul and British, and as such is perhaps the key to the whole show.

Click on 'View document' to see plate 9, the Saloon.

What our investigation suggests is that the Pavilion increasingly displayed an eclectic confederation of styles: neoclassical, Gothick, Chinese and Indian. Some of the original furniture seems also to have had a distinctively Egyptian flavour. Contemporaries would not have been bothered or surprised by this.

Exercise 7

Click on 'View document' to open an extract from Maria Edgeworth's novel The Absentee.

Turn to the extract from Maria Edgeworth's novel The Absentee (above). The first part of this passage depicts an interview between an interior designer, Mr Soho, and a prospective client, Lady Clonbrony, a would-be social climber over from Ireland. They are discussing new decorations for the gala party which Lady Clonbrony fondly hopes will launch her as a leader of London society. Make a list of some of the more exotic styles Mr Soho is trying to sell.

Discussion

I have noted down that Mr Soho recommends furniture and hangings apparently inspired by a fantasy of the Middle East: ‘Turkish tent drapery’, ‘seraglio ottomans’ and other ‘Oriental’ furniture, ‘Alhambra hangings’ (which feature a dome), and ‘Trebisond trellice’ wallpaper. He also recommends ‘Egyptian hieroglyphic [wall]paper’ with an ‘ibis border’ which had at the time quite different connotations – of Napoleon's archaeological expeditions. He suggests too a ‘Chinese pagoda’. These recommendations, combined with the profusion of mythical and exotic animals and birds which he mentions as possible adornments (chimeras, griffins, cranes, sphinxes, phoenixes), make it clear that the Pavilion's fantasy world was more mainstream in temper than perhaps it looks nowadays – albeit much more expensive than Lady Clonbrony's temporary decor.

Edgeworth's Lady Clonbrony was destined for social mortification despite laying out her money on both the Turkish tent and the Chinese pagoda, but the association of these extreme styles with entertaining and with the display of a virtuoso and promiscuously exotic taste designed to secure social status is very much what the Pavilion was about.

We have now traversed the whole of Holland's Marine Pavilion, and before we turn our attention to Nash's extensions – the two extraordinary rooms that open from either end of the Long Gallery, the Banqueting Room (interior decoration by Robert Jones) and the Music Room (interior designed by Frederick Crace) – we need to catch up on the prince's projects for massive extension to his holiday home which began to gather speed in 1815.

5 ‘Indian’ on the outside

In 1801 and 1805, first Holland and then his assistant William Porden (1775–1822) had been commissioned to make sketches for altering the exterior to a Chinese style so as to match the extravagantly Chinese interiors, but these projects remained unfulfilled ( Plate 14 ). Drawing on the pictorial records brought back by William Alexander from Lord Macartney's embassy in 1792, Holland and Porden had attempted to invent a Chinese taste in English domestic exteriors, but instead the prince was seized with a new enthusiasm for the Indian – or, to be more precise, the Mogul (rather than the Hindu).

Click on 'View document' to see plate 14, Design for a proposed Chinese exterior.

His first foray in this style concerned the stables, built between 1803 and 1808, which housed some 60 horses and dwarfed the Pavilion itself. Although Soane's master, George Dance, had designed the London Guildhall in 1788 in a subtle blend of Islamic and Gothick forms, with the Islamic deriving from illustrations of the Taj Mahal, the immediate inspiration for the prince's stables seems to have come, via Porden's acquaintance with a man called Samuel Pepys Cockerell, from the brothers William and Thomas Daniell, who in 1795 began publishing a series of volumes of sketches entitled Oriental Scenery (for an example, see Plate 15 ).

Click on 'View document' to see plate 15, Design for a proposed Chinese exterior.

This best-selling work included many aquatints of Delhi, and inspired Cockerell's designs for the new house that his brother, Sir Charles Cockerell, newly back from India and flush with what was slangily referred to as ‘nabob’ wealth, commissioned him to design at Sezincote in Gloucestershire.

Sezincote is near Moreton-in-Marsh. Although entirely neoclassical in its interior decor, its exterior and its garden are the products of a scholarly eyewitness interest in the civilization of India (see Dinkel, 1983, p.40). Contemporary European interest in India was quite different in kind from the eighteenth-century interest in things Chinese, for it was consciously scholarly and intellectual. In Germany, for example, Goethe read Sir Charles Wilkins's translation of the Bhagavad-gita (1795).

In Britain intellectuals as politically diverse as the Poet Laureate Robert Southey and the radical atheist Percy Bysshe Shelley were taking their cue from the scholar Sir William Jones's important and arcane translations of Hindu religious poetry, and the translations of Sanskrit literature and philosophy encouraged by the imperialist Warren Hastings. Southey's poem The Curse of Kehama (1810) and Shelley's The Revolt of Islam (1818), each complete with a vast apparatus of scholarly footnotes on Hindu and Muslim religious observances, respectively, were jostling each other on the shelves of the booksellers.

The ‘Indian’ style was therefore a recherche, even an austere, though noble and sublime, style to adopt. The style had other connotations too. It was inevitably and increasingly associated with Britain's rapidly growing military and trading empire. New British interest in Indian culture came back with the nabob wealth of the East India Company and the many scholars and travellers associated with it.

The events of 1803, when the British finally occupied Delhi, prompted an explosion of interest in the imperial romance that the subcontinent promised.

Sezincote House drew very precisely from the styles of ‘Mogul’, as you can see if you compare the engravings of the Jami'Masjid and Sezincote House (Plate 15, above, and Figure 10, below).

As you can see in more detail from Plates 16 and Plate 17 (photographs of the house), Sezincote is still fundamentally a neoclassical building in its symmetrical facade of balancing windows and bays, and although you can't see this from these photographs, it is set in a conventionally eighteenth-century fashion so as to dominate its wide sweeping grounds.

Click on 'View document' to see plate 16, the facade of Sezincote.

Click on 'View document' to see plate 17, another view of the acade of Sezincote.

If the ground-plan is still neoclassical, however, the rotunda has metamorphosed into a Mogul dome; the parapet has sprouted mini- minarets; the arches of the windows, hooded and recessed, have broken out into scallops and flirt upwards into little bunches of plumes or palms; and the squared-off columns flanking the front door are rather definitely neither Roman nor Greek. The gardens, on the other hand, are conspicuously Hindu in inspiration.

Down the side of the house runs a small brook which has been converted into a picturesque garden originally designed by the leading landscape improver Humphrey Repton (Figure 11 and Plate 18 ). This landscape aesthetic privileges the irregular, the interrupted, the varied and the rough in texture; here, it is heightened by an admixture of the exotic.

Click on 'View document' to see plate 18, the fountain at Sezincote.

At the head of the valley there is a carefully reconstructed Hindu temple occupied by a statue of the Hindu sun goddess Souriya, looking down over a lotus-shaped temple pool. The stream winds down, under a bridge complete with Brahmin sacred bulls, into the serpent pool which boasts a three-headed serpent spitting a fountain of water (along with the lotus, the serpent was a symbol of regeneration), strongly reminiscent of the serpents winding round the columns in the Music Room Gallery. The ‘Hindoo’ temple is characteristically stepped and squared off, its silhouette very different from that of the Mogul dome and minarets. The garden has a definite flavour of a wish to be Coleridge's

… deep romantic chasm which slanted

Down the green hill a cedarn cover!

A savage place! as holy and inchanted

As e'er beneath a waning moon was haunted

By woman wailing for her demon-lover!

Figure 10

Figure 11

But Coleridge's poem was known at this time only to a few intimates. After visiting Sezincote, the prince, as alive as his niece Queen Victoria would be half a century later to the romance of empire, with himself at the centre of the dramatic spectacular, summoned Repton to design something in the same style. Repton's enthusiasm had only been whetted by his designs for the Sezincote gardens; he had become persuaded that architecture and gardening were ‘on the eve of some great future change … in consequence of our having lately become acquainted with the scenery and buildings of India’ (quoted in Summerson, 1980, p.103). Again in the Mogul style, Repton's designs were ready in 1806 and published in 1808, but were never executed because the prince's finances were at breaking point. The actual building of the exterior of the Pavilion as we see it today was left in the event to John Nash, who would work in part from Repton's designs. Nash began work on the designs in 1815, and the Pavilion was completed in 1823.

Before we look in some detail at Nash's designs, we need to pause to consider the question of what Mogul architecture might have meant to the prince and his contemporaries, as opposed to Hindu styles. The happy congruence of Mogul and Hindu at Sezincote, which found itself reflected in the indiscriminate way that contemporaries would occasionally refer to the architecture of the Pavilion as ‘Hindoo’, was not uncontested.

This was for a variety of reasons – aesthetic, religious and political. Aesthetically, Mogul architecture was more congenial to Regency fantastic architecture because it had definite affinities with the other main fantasy mode we've already touched upon, the Gothick. You can see this from Plate 19, a photograph of the Regency wing added in Gothick style to Lacock Abbey in Wiltshire.

Click on 'View document' to see plate 19, Lacock Abbey in Wiltshire.

The lacy effect here could just as well be given another twist to become Indian, while the medieval pinnacles could easily metamorphose into minarets, given a little more latitude. As for the religious perspective, Islam, unlike Hinduism, was monotheistic rather than polytheistic, and this seems to have sat better with western cultural expectations at the time. Besides, Hinduism was increasingly being associated in Britain with the practice of suttee, the self-immolation of a widow on her dead husband's funeral pyre, dramatized for example in the opening of Southey's poem The Curse of Kehama.

So much outrage did this provoke in Britain that it would eventually become a moral impetus for the outright take-over of political power in India. Politically, the Moguls (unlike the Hindus) were also associated with fabulously successful empire-building of the sort that the British now aspired to, and with a model of government that contemporaries typically referred to (generally critically) as ‘Oriental despotism’.

Now Regent as a result of his father's incapacitating illness, the prince seems to have wished to dramatize his increased importance – indeed, it seems to be true that he felt it was part of his role to dramatize national and imperial glory and status both in his person and in his palaces. Certainly, when he became king he was to commission Nash to build him a series of buildings in London that were conspicuously national and imperial in flavour, including Marble Arch.

In these years as Regent, his native extravagance was now licensed by his status as monarch in all but name, and he promptly began to play out his own vision of himself as an absolutist ancien regime prince in architectural terms. The Pavilion, newly conceived by Nash, was in effect to give him the character of an Oriental potentate; in this context ‘Eastern magnificence … stood for the assertion of monarchical privileges … in a time of revolution, political, intellectual, and economic’ (Dinkel, 1983, p.48).

Turning to Nash's designs, let's compare the Pavilion's facades with those of Sezincote.

Exercise 8

Look again at the illustrations of Sezincote (Figures 10–11 and Plates 16–17, above) and then at those of Nash's designs for the exterior of the Royal Pavilion (Plates 1–2, below). You may also want to revisit the video for the detail of the Pavilion's exteriors. Make a list of similarities and differences.

Click below to view images referred to in exercise.

Click below to view clip 1 of the video, featuring detail of the Pavilion's exteriors.

Discussion

Similarities. Clearly, Sezincote and the Pavilion both make use of the form of the onion dome topped with a spike. They also share an interest in the style of a minaret, with its mini-dome and smaller spike as accenting features. The same battlemented effect along the edge of the roof (a variant on the standard Georgian parapet) is apparent too. Moreover, a significant number of the windows of both the Pavilion and Sezincote are arched and decorated with scalloping. The lacy effect of the railings at Sezincote also finds an echo in the stone lace-work shading the veranda of the Pavilion's east front. Finally, the squared-off columns of Sezincote are reworked in the many squared-off columns of the Pavilion.

Differences. The overall effect, however, is very different, isn't it? Of course, the Pavilion is larger, which makes some difference, but the real aesthetic contrast is that the design of the Pavilion values profusion. In place of one dome we have ten of varying but much larger sizes; in place of four modest minarets we have ten, much taller and more prominent. Where Sezincote lies quite squat and four-square, evidently a neoclassical design with the Mogul superimposed, the Pavilion, thrusting upwards with strong verticals, is conceived as upwardly mobile (you may also wish to refer to Plate 20 (below) a cross-section through the Pavilion). The Pavilion has also broken out into two tent-like structures, which don't seem to have anything to do with Mogul architecture, although they hint at desert romance. Thus, if one building advertises solid wealth (and admits where it came from), the other breathes fantasy; if one displays a fastidiously scholarly taste indulged among conventional landed proprieties, the other is a wild set of variations upon a theme. One is arguably ‘Indian’, but the other is visibly invested in a fantasy of ‘the Orient’. Indeed, Nash's unpublished preface to his Views of the Royal Pavilion remarks that the primary aim of prince and architect was to achieve an effect ‘not pedantic but picturesque’ (quoted in Batey, 1995, p.68).

Click on 'View document' to see plate 20 a cross section through Brighton pavilion.

6 The Pavilion and the picturesque

Nash's evocation of the picturesque as an aesthetic to describe the projected exterior for the Pavilion is striking. If neoclassical Palladian houses had stood four-square in the landscape, rising up out of extensive lawns and commanding an elaborately naturalistic landscape of grazing sheep and cattle to the horizon diversified by an ornamental lake, the picturesque house was instead enfolded within and extended by its garden.

Repton and Nash, in partnership from 1796 to 1802, were two of the most important exponents of picturesque garden design, deriving their practice from their personal association with the two theorists of the picturesque, Uvedale Price and his friend Richard Payne Knight.

The picturesque garden was characterized by sinuous shrubberies, flowerbeds, trellis-work and ornate garden seats, conservatories, flower corridors and trellised verandas (see Batey, 1995, p.5). The informality of serpentine winding paths and asymmetrical beds was typically punctuated by small buildings in various fantasy architectural styles ranging through the classical, the Gothick, the rustic, the Chinese and so on. (The house and grounds of Blenheim Palace in Oxfordshire provide an excellent example of an early eighteenth-century landscape ‘improved’ by Capability Brown; Luscombe Castle in Devon, by contrast, is an excellent example of the picturesque style.)

The charming connotations of dream, escape and fantasy that had characterized the garden follies which dotted the Rococo garden earlier in the eighteenth century had grown to magnificent size in the Pavilion itself.

Nor was this picturesque aesthetic confined to the exterior of the Pavilion and its setting; it also conditioned some of the feel of its interiors. In Repton's and Nash's time, the immediate garden became thought of as an extension to the house. Interiors broke out into trellised and flowered wallpaper, and flowed out into conservatories; Edgeworth's The Absentee describes Lady Clonbrony's supper-room decorated with trellised paper.

Sir John Soane himself decorated Pitzhanger Manor with trellis-work and flower sprays. London-based party entrepreneurs would undertake to expand this aesthetic, tenting and illuminating their clients’ gardens, and filling such marquees with draped muslin, vast mirrors and huge flower arrangements (Batey, 1995, p.23).

In particular, four elements of the Pavilion's interior might point the way towards thinking of it as an exercise in translating garden aesthetics into an interior:

The characteristic confusion of inside/outside. It could, after all, be said that the Pavilion both was inspired by the idea of the sort of temporary party structure in the garden erected by Nash himself for the prince's Carlton House fete in honour of Waterloo, and took the place of such a structure. It was a permanent marquee created especially for parties. The prevalence of ceilings painted to look like skies – as in the Saloon and later the Banqueting Room – and of wallpaper designed to look like trellised veranda or garden pavilion underscores this.

The strong element of fantasy. While there were fantasy interiors (perhaps most notably in the Strawberry Hill Gothick mode), this sort of fantasy has a much more robust history in garden design, including a proliferation of Chinese garden temples and pavilions in the gardens of the wealthy across the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

Its investment in restless, sauntering admiration. This interior is designed as a form of entertainment in itself, and is to be appreciated by walking around the house (rather than, say, sitting down in one place).

Its interest in how the figures of guests interacted with the ‘landscape’ . In the Rococo garden and the great landscape gardens, the guests were expected both to delight in and admire the landscape, and to figure in it to give it scale and to inhabit its scenario. Thus Horace Walpole on visiting the great landscape garden of Stourhead in Wiltshire, embellished with classical temples, rustic hermitage and grotto complete with river god, found himself rather to his disgust embarking in a boat upon the lake for a thoroughly damp English picnic, really because the genre of the garden demanded it. Equally, one of the more notable effects of exotic architecture and furniture was the way they demanded certain stock responses of astonishment, admiration and delight, at the same time incorporating guests into their own fantasy.

These reactions are gratifyingly expressed by one of Lady Clonbrony's guests at her gala:

The opening of her gala, the display of her splendid reception rooms, the Turkish tent, the Alhambra, the pagoda, formed a proud moment to lady Clonbrony. Much did she enjoy, and much too naturally … did she show her enjoyment of the surprise excited in some and affected by others on their first entrance.

One young, very young lady expressed her astonishment so audibly as to attract the notice of all the bystanders. Lady Clonbrony, delighted, seized both her hands, shook them, and laughed heartily; then, as the young lady with her party passed on, her ladyship recovered herself, drew up her head, and said to the company near her, ‘Poor thing! I hope I covered her little naivete properly. How new she must be!’

Edgeworth's account of the party goes on to describe the ways in which guests are transformed into props within the overall fantasy provided by the decor:

Then, with well practised dignity, and half subdued self-complacency of aspect, her ladyship went gliding about – most importantly busy, introducing my lady this to the sphynx candelabra, and my lady that to the Trebisond trellice; placing some delightfully for the perspective of the Alhambra; establishing others quite to her satisfaction on seraglio ottomans; and honouring others with a seat under the statira canopy.

The guests themselves are to be picturesque, ‘dispersed in happy groups, or reposing on seraglio ottomans, drinking lemonade and sherbet – beautiful Fatimas admiring, or being admired’. The Pavilion furniture similarly insisted upon picturesque Oriental poses. The witty and sophisticated Princess Lieven wrote:

I do not believe that since the days of Heliogabulus there has been such magnificence and luxury. There is something effeminate in it which is disgusting. One spends the evening half-lying on cushions; the lights are dazzling; there are perfumes, music, liqueurs.

[ Heliogabulus is discussed further in section 9 of this unit. ]

(Quoted in Roberts, 1939, p. 110)

As such the Pavilion was itself a sort of extended party game: a stage-set for private theatricals, for a masquerade, for tableaux vivants, with a faintly naughty edge. It was an aristocratically exclusive re-creation of the public delights of Vauxhall Gardens, a place haunted by the prince in his wild youth.

7 Experiencing the exotic

So far we have looked in some detail at the interiors of Nash's Pavilion, with the important exception of the Banqueting Room (decorated by Robert Jones) and the Music Room (decorated by Frederick Crace). Both were designed as coups de theatre and it is this aspect of these rooms that I'd like you to focus upon now.

Exercise 9

Return to clip 3 of the video and look again at the Banqueting Room and the Music Room. You may also wish to look at the contemporary depictions of these two rooms in Plates 8 and 11 (see below), and to look at the contemporary guidebook descriptions of the rooms given in the AV Notes. Spend a little time practising picking out the Chinese, Indian, Gothick and neoclassical elements which go to making up this Romantic decor, and then make some notes about what effects the rooms achieve and how this is done. Be especially alert to the possibility of ‘special effects’, such as trompe l'oeil and games with perspective.

Click below to view clip 3 of the video, featuring the Banqueting Room and the Music Room.

Click 'view document' to see plate 8.

Click 'view document' to see plate 11.

Click on 'View document' to read the AV notes for the video clips.

Discussion

Both rooms, stripped of their decor, turn out to be not at all unlike Soane's neoclassical halls at the Bank of England. Architecturally, they are both domed square spaces with two lateral extensions, classical in spirit and in principle. That said, however, where Soane's rooms are constructed of real arches and real domes, Nash's arches are not actually supporting anything but are mere wall ornaments in relief. And this tricksy quality is perhaps above all what distinguishes the Romantically improbable style of these rooms from Soane's weightiness and insistence on functionality.

The Banqueting Room. The Oriental magnificence of this room deliberately confounds both chinoiserie (e.g. in the dragons, the wall-paintings, the mini-pagodas sheltering the doors and painted on them) and the Indian (expressed most strongly in the ceiling conceit of the trompe l'oeil plantain tree and the lotus glass shades of the huge and dazzling central chandelier). The mixing of the two styles provokes a dramatic conflict between the glamorized violence of the writhing monsters and the sentimental and delicate domesticity of the panels depicting Chinese life.

Jones here achieves a distinctively Regency effect compounded of massive scale and overpowering detail. Entering the Banqueting Room from the Chinese gallery – low-ceilinged and bewilderingly and disorientatingly mirrored – is an astonishing experience. Dreamlike, the scale suddenly expands from the human to the enormous, and the effect is heightened by the apparent glimpse of sky at the apex of the dome. These games of scale also on occasion included miniaturization. The prince briefly brought in the extraordinary talents of Marie-Antoine Careme, the greatest cook of his day, tempted over from France to act as royal chef in the Pavilion's extraordinarily technically advanced kitchens. The confectionery set-pieces for which he was famous were characteristically fantasy buildings in miniature. They included La ruine de la mosquee turque (ruin of a Turkish mosque) and L'hermitage chinois (Chinese hermitage), made in icing-sugar and set under that astonishing dome. Generally, much of the effect of this room results from the repetition of the same images but on multiple scales: notice, for example, how the lotus and the dragon are repeated.

The Music Room. Again, the scheme for this is late chinoiserie – and as it is designed by Crace it is lighter in feel. Some of the same tricks of scale are also in evidence here in order to astonish guests. These too are centred on the ceiling, which as you will have seen is built up of gilded cockleshells. An effect of greater height was achieved by diminishing the size of the cockleshells towards the apex of the dome, and by changing the tones of the gilding towards the apex. Less obviously, the wall-paintings evoked for contemporaries paintings on Chinese lacquer boxes: the effect was therefore to shrink the spectator within a Chinese miniature grown gigantic. Again, too, the room repeats the same motifs: of serpents, lotus and dragon, varying in scale and prominence, but providing a unifying feeling. The painstaking detailing has a faintly dreamlike effect – fix your eyes on the wallpaper, and sooner or later you are aware that you are looking at a dog-headed serpent, for example. Like the Banqueting Room, the Music Room also intermingles images of extreme violence (manifested in the writhing serpents and dragons) with the domestic or rural idyll, often featuring children. The juxtaposition is more than merely piquant; it introduces a characteristically Romantic tension that we'll come back to below.

We might also remark on some other ‘special effects’ built into the Pavilion which don't necessarily strike us with the force with which they certainly would have struck contemporaries. The Pavilion was very efficiently and invisibly heated via underfloor heating, an innovation which visitors then found rather stifling.

The oil-fired lighting was startlingly profuse, intense and brilliant in an era of candlelight; the thick fitted carpets deadened sound to an unusual extent; the daring and extreme colour harmonies, the many and varied faux surfaces, and the use of gas-fired backlighting behind stained-glass panels all heightened the experience, said by one contemporary observer, Mrs Creevey, to be like being inside the Arabian Nights (see the AV Notes).

Together with the use of interrupted vista and perspective, of dreamlike repetition and multiplication, of mirrors, of trompe l'oeil and of wildly inflated and metamorphic scale, the effect must have been phantasmagoric. With the addition of perfumes and music, the atmosphere was famously heady.

So far I have been concentrating upon the differences between the various rooms in the Pavilion, and upon the differences between the interiors and the exteriors. But although this has been useful for the sake of argument, it is not the whole story. For all that the Comtesse de Boigne was right in her disdainful identification of the styles of the Pavilion as ‘heterogeneous’, John Evans's remark that the Pavilion's details echoed each other from the smallest to the grandest is equally true (see the AV Notes). Looked at carefully, it becomes clear that all the different room interiors have been designed to echo each other, and to repeat shapes from the exterior too.

Exercise 10

Look once more at all three video clips. Watch them right through and, as you do so, make a list of recurrent motifs and try to sketch repeated shapes. Don't forget that the overall shape may be the same, even if it is reduced, enlarged, inverted, or pretending to be something else (e.g. a bell and a tassel may actually be the same shape, and serve the same function within the decorative scheme, while having different connotations).

Click below to view clip 1 of the video.

Click below to view clip 2 of the video.

Click below to view clip 3 of the video.

Discussion

The easiest thing to do is to make a list of motifs that recur: these include dragons, serpents, bamboo, sunflowers, stars, bells and tassels. It is more difficult to identify the shapes. My list includes:

what I shall inelegantly call ‘bobbles’ (which line the parapet on the exterior and the chandeliers in the Music Room, to take two examples);

bell shapes which, when inverted, turn into flower shapes, or, when multiplied, become pagodas;

curves flouncing round the Moorish windows and repeated on the cornice of the Entrance Hall and round the mirrors in the Saloon;

fretwork of every sort;

leaves growing both up and down (compare the base of the columns on the exterior, the leaves crowning the cupolas and the leaves on the plantain tree in the Banqueting Room, for example);

spiky star shapes;

reiterated scallops – as in the Saloon wallpaper and the Music Room dome.

The effect of this ‘reiteration with variation’ is undoubtedly to amplify the dreamlike sense of impending metamorphosis that the Pavilion achieves – you might note, for example, the effect of the way that acanthus leaves turn into dragon manes in the Banqueting Room.

This repetition of shapes and motifs produces a remarkably unified architectural ‘vocabulary’ throughout the building, despite the different overall effects that the rooms achieve. You might also have noticed the way that the costumes worn by our actors in the video echo and are at home among those apparently outre Regency shapes, combining the upward thrust of feathers (compare the flirting tufts at the top of the exterior windows on Sezincote House, for example), the long slender drag of the trains flowing away like serpents’ tails, and the horizontal lines of the bodices that double the severities of the Chinese-style fretwork.

The costumes look so at home because, idiosyncratic though the Pavilion certainly is and aspired to be, it is grounded within a definite and recognizable Regency aesthetic. George Cruikshank's satiric print The Beauties of Brighton (see Plate 21 makes this point too, though the clothes are from a slightly later year, 1826.

Click on 'View document' to see plate 21 George Cruikshank's The Beauties of Brighton.

Indeed, the artist has a lot of fun with pointing up parallels such as the tails of the gentleman's coat which reiterate the tent-like structure on the Pavilion, the top hats echoed in the minarets, and the puffy skirts and sleeves that suggest the domes. The Pavilion, this suggests, was paradoxically both exotic and mainstream in its aesthetic.

8 How ‘Romantic’ is the Pavilion?

At first glance the Pavilion's exoticism might seem to have a good deal to do with contemporary Romantic writers’ fascination with the Oriental and exotic. A widespread public interest in these modes put Byron's ‘Oriental tales’ and Thomas Moore's romance Lalla Rookh at the top of the bestseller lists. Coleridge's ‘Kubla Khan’, after all, is often regarded as the paradigmatic Romantic short poem. So, flouting the conventions of historians of architecture, who designate this period simply as ‘Regency’, in this section we're going to pursue the relations between the Romantic exotic as expressed in literature and the Pavilion in its final state.

Our investigation so far of the building's effects might already suggest some points of comparison.

Exercise 11

Make a list of some ideas and aesthetic effects that you would consider to be Romantic. (This is a way of looking back across your study to date, and should take you some time – it is not easy!) Then see if you can identify any of those ideas and aesthetic effects realized in the Pavilion.

Discussion

Some of the principal tendencies that your study has identified as being Romantic include:

The abandonment of Enlightenment ideals of knowability and reason, politeness and social responsibility, typically expressed in the neoclassical aesthetic.

The increasing emphasis put on the unknowable and irrational, and, associated with that, an interest in dreams and fantasies, the development of certain stylistic features (notably the grotesque, the ruined and the fragmentary), and an interest in the sublime.