Resource 2: Asking questions about feelings

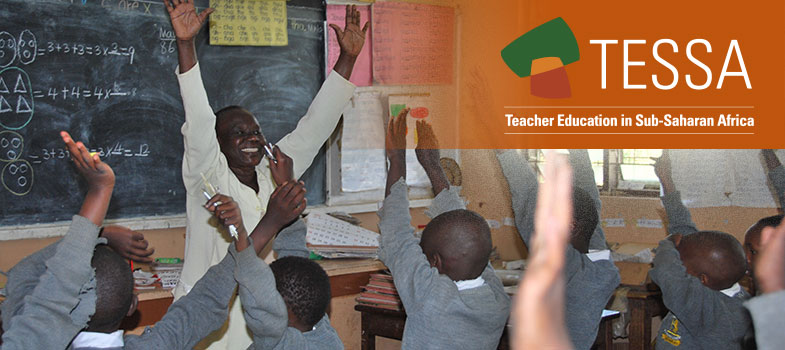

![]() Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

You need to be sensitive when asking questions about feelings. Children might not always want to talk about their feelings in public. You need to ask the kinds of questions that allow children to give answers they feel comfortable with.

One way to do this is to ask questions to the whole class instead of to individuals. Ask questions such as: ‘Who likes …’ and ‘Who doesn’t like …’ with pupils putting up their hands. If they see that they are part of a group, the children will feel less embarrassed about revealing their feelings.

You can do the same by brainstorming different questions. For example, ask: ‘What makes you scared?’ and then write all the pupils’ ideas down on the board very quickly. This way, you won’t make the individuals feel too exposed.

If you want them to talk more intimately about their feelings, organise them into pairs and groups to do similar exercises. They will probably find it easier to speak in a small group.

You can also use stories to explore sensitive ideas – this helps pupils to talk more freely as they do not feel they are talking about their own experiences.

You can make up your own stories to share with your pupils. Or you could use the story of Rwandan street children below to stimulate discussion. Either copy the sheet – one for each group – or read from your copy to the whole class.

After they have heard the story taken from World Street Children News, ask them how they feel about the children’s lives.

Are they similar or different to their own lives? How would they feel about living like that? What would they like and dislike about this kind of life?

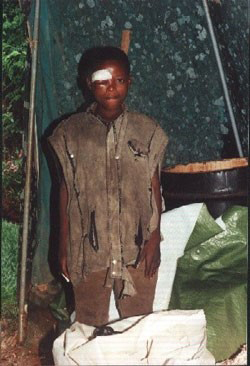

Rwandan street children

Judith is a 14-year-old girl. She and a few other girls and boys of her age take shelter on the streets of Kigali. Judith says she was born in a rural village in southern Rwanda. After two years of school, her family kept her at home to help with household chores. Her mother died when Judith was nine years old. ‘My father is a drunkard,’ she says with evident bitterness. ‘Within four months after my mother's death he remarried another woman.’

She says her stepmother abused her and her siblings verbally and physically. Worse, she says, her father took side with her stepmother. She says that after the stepmother came, she and the other children were completely neglected. Her father was drunk and her stepmother saw the children as a burden. She says that after the stepmother arrived, their house became ‘a hell’, that they were in ‘deep misery’: They didn't have enough to eat, they didn't have proper clothing and they didn't go to school.

How she became a street child (mayibobo)

‘One by one, all my elder sisters left home for the town [Kigali] in order to survive. They worked in different parts of Kigali as housemaids. One day, my father and stepmother forced me and my brother to go to Kigali to find work like my sisters. That was two years ago. I was just 12 years old. We came to the main market in Kigali and spent three or fours days in the surrounding neighbourhoods. Sleeping on the street was really a horrible experience for me. I was just like an orphan, though most of the members of my family were alive.

By God's grace, I came across a rich woman in the market who was ready to take me to her house and give me a job. Since my brother couldn't come with me, he decided to be a mayibobo. The woman’s house was at Nyamirambo in Kigali. I was asked to look after her toddlers and to do other work such as cleaning the bathroom and washing clothes. She told me she would pay me 3,000 Rwandan francs (US$7.50) every month. Initially, I was so happy just to have a house to live in.

As days went by, I got accustomed to the new environment, but my happiness didn't last long.’ She says that when her boss was gone, her boss’s husband sexually abused her. She says she ‘became prey to his lust’. This went on for two months. When her boss found out about the husband's behaviour, Judith was sent away. She says she was never paid for the three months she worked at the rich woman’s house.

I ask what happened to her after she left the rich woman's house. ‘I tried without luck to get some sort of similar work,’ she says. ‘I didn't know where to go, so I came to the market again. I met my brother and his friends and became a mayibobo.

Taken from: http://www.worldpress.org/Africa/355.cfmResource 1: Similarities and differences