Rural entrepreneurship in Wales

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Saturday, 14 March 2026, 12:58 AM

Rural entrepreneurship in Wales

Introduction

This course considers the issues that are important when starting up or running a small business in a rural environment.

Traditional business models apply to running a business in any location. This course will introduce you to some concepts that will help you work out what you want to do with your business idea. It will also ask you to consider the impact of living in a rural location on your business and to consider what is important to you.

Here are some characters who will be with us throughout the course. Each has a different proposal for which the rural context poses particular challenges.

Euan works on his family’s farm and wants to develop more income by diversifying outside of traditional farming activities.

Gwyneth is a keen cook and has had her hours reduced at the café where she works in town. To supplement her family income, she wants to sell her homemade jams, chutneys and preserves at farmers’ markets and food fairs.

Julia, a Further Education student, lives with her family in a remote area where the Post Office and village store are threatened with closure. She needs to engage in a team enterprise activity as part of her Welsh Baccalaureate qualification and has been inspired by enterprise events and lectures attended at college. With the support of staff at the Post Office, she wants to lead local residents in a bid to take over the Post Office and store and run them as a community shop.

Dafydd is a sheep farmer who, together with his wife Ffion, works off farm to supplement the farming income. He wants to diversify into the holiday let business by turning three redundant barns into eco-friendly self-catering accommodation.

Gwenllian is a language teacher living in a fairly remote area of mid-Wales where access to learning is difficult (long distances, poor public transport and inflexible timetables). She has identified a need for language-based CPD and translation services among local businesses involved in exporting their products to mainland Europe.

Whatever your motivation for tackling this course of study, it will take you on a journey looking at the challenges posed when you live in a rural environment and start you thinking about how you can use this knowledge to run a successful business of your choice.

This OpenLearn course is an adapted extract from the Open University course Q91 Business Management.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

understand the importance of how living rurally influences your business or social enterprise objectives

explore the feasibility of a business idea

plan a strategy for the development of your company

state the likely resources and capabilities required for your new business and understand where the gaps are likely to occur.

Unit structure

This course should take approximately 30 hours to study, but it has been carefully designed so you can choose your own pace of learning. The materials are designed for study at your computer screen (but sections can be printed out to read elsewhere) in short periods – half-an-hour now and then wherever you are.

While it has been designed so that you can study it on your own, as an Open Educational Resource (OER), you can also download content and reuse, revise, or remix it for use in other contexts. We have tried to ensure that the content is as flexible and adaptable as possible. This means it should be easy to use in face-to-face contexts with, for example, a group of other entrepreneurs or community members (community enterprise) as well as by yourself, alone, online. The Resources section at the end of the course contains templates used in the course to download.

We have set up a Twitter account, @RuralEntWales. You can use this to find up to date information about the changes in the rural entrepreneurial landscape.

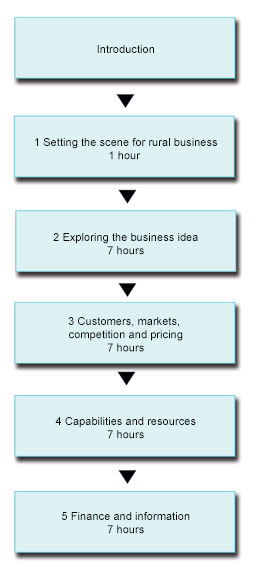

The course map below indicates the sections of the course together with guidance on how long each section might take, enabling you to plan your study time. The learning outcomes describe what you can expect to have learned at the end of your study.

Introduction; 1 Setting the scene for rural business, 1 hour; 2 Exploring the business idea, 7 hours; 3 Customers, markets, competition and pricing, 7 hours; 4 Capabilities and resources, 7 hours; 5 Finance and information, 7 hours.

As you progress through this course you will start to complete a plan, by filling in the Business Plan Progress Review (BPPR). Although the BPPR is too brief to be considered a full business plan, it will help you review the key elements of your business idea and will be extremely helpful as a summary document. The BPPR is available to download in the Resources section.

As you launch your new business idea – and if you intend to secure finance for your business – you will need a business plan with more detail than this course provides, so it is a good idea to work on two versions of the plan as you progress through the course.

1 Setting the scene for rural business

Learning outcomes

At the end of this section you will be able to:

- understand how living rurally influences your business or social enterprise objectives

- set business goals within a framework for living rurally

- articulate the importance of personal values in setting up and running a business.

1.1 What does rural mean?

How do we define what is rural? Before we move on to any official definitions or statistics, it might be worth looking at what we think is meant by the term ‘rurality’. Often when we think of ‘rural’ we tend to perhaps equate it with ‘the countryside’, or ‘landscape’, or ‘nature’, or other similar general terms. Perhaps we might think about ‘quality of life’, a slower pace, stronger communities. We might think about some things that relate to descriptions of the physical world around us and some that relate to social or cultural aspects. Sometimes they might be positive (as above), but others might be negative: everybody knowing your business; difficult to access services like education or health care; poor roads and transport links, and lack of employment opportunities. Defining ‘rurality’ is by no means straightforward, but it is important to understand and recognise the benefits and costs of living in a rural area.

It is worth recognising that not all rural areas are the same, and that the rural context and rural challenges within each of the four nations in the United Kingdom (Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland and England), and regionally within these nations, will be very different. Within Wales, the rural challenges of Pembrokeshire, for example, will be very different to those experienced in Conwy, andeven within Pembrokeshire, between Narberth and St. Dogmaels.

New findings, released by the ONS, show that Wales continues to have many of the most empty areas in the United Kingdom. Powys, with only 26 people per square km, is the second most empty part of the UK. For comparison Cardiff has 2,482 people per square km. The average weekly earnings of those living in rural areas such as Powys is lower than the Welsh national average. Anglesey and Conwy have the highest number of economically inactive, retired residents in Wales.

The Rural Development Plan (RDP) for Wales 2009–2013 outlines four axes that provide strategic direction to regional and local rural development initiatives:

- Axis 1: Making rural Wales more competitive

- Axis 2: Protecting our countryside

- Axis 3: Improving people’s lives and encouraging diversification

- Axis 4: Supporting local projects and initiatives

Each region in Wales, as part of the Wales Rural Network, has its own Local Action Group which then applies the RDP strategy according to its own situational needs.

This kind of information is useful as background when thinking about your business and your community.

Note: A link to the 2014–2020 version of the RDP for Wales will be made available via the Twitter hashtag #RDPWalesRuralEnt.

The affordability of housing in rural areas has long been an issue across the UK, and particularly in Welsh communities, where the price of local houses is out of step with the level of local incomes. This situation is exacerbated by the extent of second home ownership in many rural areas, as well as the influx of city dwellers looking for ‘a mixture of clean air, friendly people and community spirit’, according to the NFU Mutual study (2010). The study claims that nearly seven in ten of rural residents have exchanged towns and cities for the Welsh countryside, and that around 45 per cent have moved from urban areas in the last five years. While this has helped local services to survive, it has also pushed up house prices according to The Campaign for the Protection of Rural Wales (CPRW).

Research conducted by The Wales Rural Observatory (2009) for the ‘One Wales’ coalition government in 2010, found that other challenging issues for those living in rural areas include the relatively high cost of goods (including fuel), transport difficulties and poor access to broadband. Nevertheless, more than 90 per cent of those surveyed said they were satisfied with their local area as a place to live, and 94 per cent rated their quality of life as either ‘very good’ or ‘fairly quiet’.

The public sector is a major employer in Wales, and in rural Wales it accounts for 28 per cent of the workforce. There is considerable regional variation, however. Therefore, almost a third of the workforce in Gwynedd and Carmarthenshire work in the public sector whereas less than a quarter of the working population do so in Pembrokeshire, Powys, Conwy and Monmouthshire. As the size of the public sector shrinks, its impact will be felt keenly in rural Wales.

In 2006, small and medium-sized enterprises made up over 99 per cent of the 190,000 businesses in Wales but accounted for less than 60 per cent of employment (Stats Wales, 2009).

Rural areas have the highest density (per head of population) of private business small employers (Powys, Ceredigion and Pembrokeshire ranking 1st, 2nd and 3rd, Wales.gov, 2011), 17 per cent of whose employees are aged under 25. In addition, under 40 per cent of those who work in the private sector speak Welsh with under a half using the language ‘mostly’ or ‘sometimes’ at work (Wales Rural Observatory, 2006).

CO2 emissions are higher in rural areas, transport use tends to be higher, and rural properties tend to be less well insulated. However, rural communities have the greatest potential to benefit from renewable energy.

What these kinds of ‘facts’ tell us is that rural areas experience different sets of issues. Knowing those issues, and reflecting on and understanding how they might affect your business and your choices will help you to develop your business, and give potential funders confidence that you have done your research. For the latest information look for #RDPWalesRuralEnt on Twitter.

Local Authorities (LA) also gather data about your area; it is worth exploring these either by going directly to your Local Authority’s website or by going to the Business Wales website where you will find links to all of the 22 LAs as well as additional information and support.

At the end of this section we suggest some possible sources of information and support.

Task 1: Personal objectives

Write down your personal objectives for studying this course. (You can modify this as you progress.)

- What do you enjoy about living in a rural location? What do you not enjoy?

- Write down what ‘rurality’ means to you i.e., what are its characteristics (this might help you think about what it is it that being rural brings to your business).

Share your thoughts with other entrepreneurs in your local networks.

At the end of each section you will be asked to review the activities you have completed and summarise your work in the Business Plan Progress Review (BPPR).

Take a look at the template now so you are clear about what you will need to do in each section.

1.2 Why start a business?

For some, living rurally has special benefits, and for others it is about making a difficult life more manageable.

Before you examine the feasibility of your business idea, take some time to think through who your stakeholders are and what your strategies are for taking the business forward. This is useful to understand the basis on which you are building the business. This is about you, what is important to you and how this will be reflected in your business.

Task 2: Visioning – life and business

Write down your personal goals for 12 months’ time and for five years’ time. What would you like to have achieved? Include personal and business objectives. Use the table template as below or, if you prefer, create your own mind map (Buzan, 2002) or list.

| Area of my life | 12 months | Five years | Comments and links |

|---|---|---|---|

| Home – living rurally | a. b. c. | a. b. c. | |

| Family | a. b. c. | a. b. c. | |

| Work | a. b. c. | a. b. c. | |

| Values | a. b. c. | a. b. c. |

Look at your table, mind map or list. Does anything strike you? Are your goals compatible?

It is important to understand what it is about where you live, how you live, your desires and your fundamental values that you will take with you into the new venture.

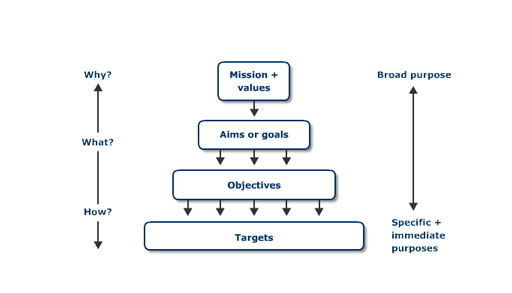

Every organisation, large or small, has a ‘pyramid of purpose’.

Three headings spaced evenly down page: Why? [arrow to] What? [arrow to] How?. Four boxes, arrows between them, boxes increase in width: Mission and values [arrow to] aims or goals [arrows to] objectives [arrows to] Targets. Two headings: Broad purpose (level with 'missions and values') [arrow down to] specific and immediate purposes (level with 'Targets).

As we progress through the course, your aims, objectives and so on will become clearer. This diagram shows how they all need to align, to build upon and support each other.

Task 3: Mission statement

One of the things that can help us understand our own business idea is to reflect on our previous work experiences. Think about an organisation in which you have worked.

- Can you state its general mission and values?

- Do you know its aims or goals?

- Were its objectives (or those of the department you worked in) clear?

- Did you have formal (or informal) targets?

Discussion

If you have worked in a large organisation you may have seen the company ‘mission’, vision and values on posters, etc. These things are seen as important in creating a culture or ‘way of doing things’ within the company.

In smaller companies not so much time is usually given to communicating them in such a formal way. Nevertheless, when you go into a small shop or company you sense what is important by the way business is conducted (how staff behave towards customers, the lighting and lay out of the premises and how this makes you feel, and so on).

It will be the same for your business: the values you work to will be your own. How do they transfer to the business world given that you need to make a profit in some way, even if it is to be reinvested in the business?

It is common for large companies to have a ‘corporate social responsibility’ policy, and for some smaller organisations it is part of their very being (e.g. community shops and cafés). Wherever such a policy fits in your business, it can provide a helpful point to reflect your personal values formally within your business.

1.3 Values

All businesses have values, which are influenced by the world around them. The acronym SOGI helps us to think about them.

- Society: Every organisation operates within societal norms: they might relate to faith, environmental aspects, historical traditions, geographic or cultural practices. These will vary. Earlier, we explored our own perceptions of rurality, and discovered that rural areas vary and that our position in rural society (young/old/less able/employed) changes how we experience rural life.

- Organisational: A founder of an organisation imparts their own beliefs and values into the way the company is run. Some of these will relate to the aspects above and be unconscious, others may be a wish to resist or move away from established ways of doing things. These are then taken on by the staff and become embedded into the way they are expected to behave. We may do the same ourselves.

- Group: Within an organisation a group can develop their own set of values, ways of communicating and behaving with each other.

- Individual: Our personal values and beliefs will ‘fit’ or not with those of society, the organisation and the groups in which we find ourselves. People usually give their best when the ‘fit’ is good.

Task 4: Values

Think about the values you bring to your new enterprise.

If you are planning a partnership, think about the values of each person involved. (You could ask them to complete the previous activity too!)

- Are you and your partner’s values compatible?

- How will your values be evident in your organisation?

- If you are extending an existing business: what are the existing values of the business?

- Are you happy to build on them?

Make notes of your thoughts.

Share your thoughts with other entrepreneurs in your local networks.

1.4 The rural entrepreneur

Originally, the term ‘entrepreneur’, which derives from the French words entre (between) and prendre (to take), referred to someone who acted as an intermediary in undertaking to do something. The term was first used to describe the activities of what today we might call an impresario, a promoter or a deal-developing, entrepreneurial ideas maker.

Ask people to name an entrepreneur and many will say Richard Branson. He is indeed an entrepreneur, but to think that his high-profile celebrity status is necessary to entrepreneurship does a great disservice to all those who work creating new products or services or delivering them to market in a different or more efficient way.

It is also worth noting that entrepreneurship is not something that is confined to the ‘for profit’ sector. We also find social entrepreneurs, and in many rural locales policy entrepreneurs (people in public office like a local authority) can be just as important in laying the foundations for entrepreneurship.

Within a 20 mile range of any rural location there will be many examples of entrepreneurial businesses.

Task 5: Rural businesses

Make a list the businesses local to you that might be deemed entrepreneurial.

A sample of small businesses identified within a very small radius of one another were:

- A chocolate importer, originally from mainland Europe, who noted that people loved the chocolate he brought back as presents and set up a business.

- A farming family who have built a cafe and a bunkhouse to supplement their income.

- A consultancy that conducts ecological monitoring, usually for new developments. They are very busy with impact assessments on hydro schemes and wind farms.

- A range of local traders who work as sole traders but come together to take on larger projects.

- A community company that owns and manages the local fishery and is branching out into hydro.

- A self-employed machine operator with his own plant who is diversifying into the pipe business.

- A smallholder who moved into the area, set up a mushroom business selling direct to wholesalers and who has recently branched out into selling mushroom kits.

- Two guitar makers, independent of each other but living less than a mile apart. Each makes handmade bespoke instruments.

- A sole trader who develops and designs the computer systems that run climate controls in high rise buildings and most of whose clients are in SE Asia.

Discussion

Each one of these business owners started with a small idea and developed it into a sustainable business or social enterprise. It is often assumed entrepreneurs share with all other business owners and senior managers the goal of maximising the ‘profits’ of their business. Even if you are working towards a social enterprise, the long-term financial viability is still a fundamental necessity. In reality, however, many other motives and objectives also influence business and managerial behaviour, particularly among small organisations of less than 20 employees (which would include almost all new start ups).

Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter (1934) defined the entrepreneur simply as someone who acts as an agent of change by bringing into existence a ‘new combination of the means of production’. The essence of Schumpeter’s approach is that entrepreneurs are competitive and always strive to gain an edge over their competitors, or the best facility for their clients in the case of a social enterprise. In general, he suggests entrepreneurs are also adept at getting investors and providers of capital (such as banks, relatives or grant schemes) to bear the main part of the financial risk.

When entrepreneurs begin to consolidate and slow down they revert to being ordinary managers and, in Schumpeter’s terms, are no longer entrepreneurial. Thus, a certain set of skills, approaches and attitude may be required to set up a business and a different set required to run and maintain it.

McClelland (1968) takes a more psychological perspective. His preferred entrepreneurial motivator is the ‘need for achievement’ (‘nAch’, as it is usually abbreviated) – ‘a desire to do well, not so much for the sake of social recognition or prestige, but to attain an inner feeling of personal accomplishment’. McClelland was quite critical of the profit motive as the mainspring of entrepreneurial activity.

Slee (2008) purports that once a relatively low level of wealth is achieved, further increases do not mirror increases in happiness. Thus, the desire for constant growth in a small company may not enhance the ‘well being’ noted as being a key motivation for many rural businesses.

He argues that many things should happen locally, be it work, energy or food production or, indeed, leisure time. Curry (2008) suggests:

It is the pursuit of a number of these ‘non-growth’ characteristics that is enjoying increasing popularity amongst rural communities themselves … ‘bottom up’ initiatives such as land trusts, community finance solutions, alternative foods, local foods, farmers markets, etc. are all naturally adopting Slee’s notions of relocalisation on the ground.

1.5 Behavioural characteristics of entrepreneurs

Many, but not all, rural businesses are driven by the desire to provide a local service, to succeed and build the community around them. Some of those are private ‘for profit’ and some exist in the ‘not-for-profit’ sector – voluntary organisations, community interest companies, charities, or social enterprises. Of course the ‘not-for-profit’ organisations still need to make money, but that is not their principal goal and any excess profits are typically invested back into the organisation.

One idea of entrepreneurship may sit more comfortably with you than others, and indeed, you may never (until now) have considered yourself to be an entrepreneur at all. Whatever your motivation there are some key characteristics that support entrepreneurial success that were identified by Jeffrey Timmons from Massachusetts Institute of Technology. These are:

- drive and energy

- self-confidence

- high initiative and personal responsibility

- internal locus of control

- high tolerance for ambiguity

- low fear of failure

- moderate risk taking

- long-term involvement

- money as a measure not merely an end

- use of feedback

- continuous pragmatic problem solving

- use of resources

- self-imposed standards.

Task 6: Qualities of and entrepreneur

Which of these qualities do you recognise in yourself? You don’t have to have them all! For more information see What makes an entrepreneur?.

Share your thoughts with other entrepreneurs in your local networks.

1.5.1 Further information

Listen to Why study entrepreneurship? This is part of a series of recordings tracking entrepreneurs’ journeys that we will visit throughout the module.

If you have found this section useful you may also want to explore this resource on Entrepreneurial impressions. It includes a video from young Scottish entrepreneur Fraser Docherty about his SuperJam business. Or try the OpenLearn unit Entrepreneurial behaviour.

1.6 Summary

In this section you have:

- examined the definition of ‘rural’

- written your personal objectives for starting a business

- considered the pyramid of purpose, looking at the alignment of your life and business values.

Now open the BPPR and reflect on the activities completed in this section. Review the output from each activity and complete the two questions raised in the introductory section of the BPPR. This requires you to pull out the most important aspects of your thinking to date.

A wise word of experience…

Remember that as you develop your enterprise you are not on your own. Family, friends and existing networks all provide valuable support. However, there are lots of other sources of support as well, such as from public bodies. Many organisations also provide useful signposting to resources and information, advice and guidance. These will vary depending on where you live. Here is a starter list of organisations you might consider contacting or exploring (if you have not done so already):

2 Exploring the business idea

Learning outcomes

At the end of this section you will be able to:

- explore the feasibility of a business idea

- identify the stages to business success

- state the different company structures possible

- assess the impact of living in a rural environment

- understand stakeholders, identify them and their expectations

- plan a strategy for the development of your company.

2.1 The business idea

In this section you will begin to look at your idea in detail, to consider its feasibility and the perspectives of some of the others who will be interested in the viability of your idea, including any rural perspectives.

To have the power to attract, convince and motivate people with wildly divergent interests – such as customers, consumers, investors, employees, suppliers, distributors and so on – the idea must be innovative, legitimate and viable. It must offer something new, something of value to some or all of these interested parties (often called stakeholders), and its first essential step is that it must attract someone, or some team, committed to making it happen. The person who is committed to undertaking the idea we can call the entrepreneur.

However, commitment is not enough. To become reality, ideas need resources – physical, financial and intangible (such as experience, knowledge and, sometimes, legal rights to use processes and products). A key part of the entrepreneur’s job is to obtain the capital to acquire those resources.

When developing a business we draw on a range of complex capital inputs. For example, our own skills and those of anyone we employ is called ‘human capital’, our networks and connections are ‘social capital’, and the effect on the community in which we operate will be around ‘cultural capital’. Social and cultural capital might be particularly important when considering a social enterprise such as promoting inclusion for vulnerable adults, or promoting the local culture.

Many small rural businesses start with just one person, the business owner, perhaps working part-time alongside another job at the beginning. It is certainly possible (although hard work) to continue like this, even when your enterprise becomes ‘full time’. However, even if it’s just you in your business, it does not exist in isolation, it is still part of a network, where often businesses depend on each other.

Most businesses grow sufficiently so that they need to employ another person or even a group of people. It is the actions of these people that will translate the idea into a product or service. However, they do not all need to work for you. You might make a product, but you do not have to market it, or distribute it: you can employ others to do this for you. In the end you might not even end up making it yourself either but instead decide to outsource the production to someone else.

Finally, the products developed from the idea need customers and consumers who want them and are prepared to exchange their hard earned cash for them. Often you can make an enterprise succeed by meeting a local need or you may be targeting a wider market. Whatever your scale, it is likely that your business idea will have to be strong enough to secure the finance, skills and other business support to help your idea develop through to fruition. That does sound daunting, but often what is distinctive about your product or idea might be the values that lie behind it or even the location. Thus, a community owned or local shop might be expensive or stock a small range of products, but for rural residents that cost may be set against travel costs they might incur by having to travel elsewhere to shop, and they might also place a social value on supporting their local shop.

Task 7: The business idea

To be confident that your idea is strong enough to succeed in its competitive market, you will need to provide robust answers to the following questions (which, at this stage, you may find difficult – but you should have a much clearer idea by the end of the course):

- In one sentence, what is your business idea?

- What unique or distinctive features characterise it?

- What types of customers are likely to be attracted to its benefits?

- Potentially, how many customers are there?

- Are enough of them willing to pay the prices or fees to cover all your costs and provide you with a reasonable living?

Write down your answers (even if they are just initial thoughts) so that you can refer to them later.

Share your thoughts with other entrepreneurs in your local networks.

2.1.1 Case studies – business ideas

Having met our case studies in the introduction, we will now find out more about their individual business ideas.

Euan

Image of Donald, white male, aged 35, farmer, with tractor.

‘I want to make my family’s farming business more resilient and bring in more income by making use of the unused sheds and land we have. There are lots of microbreweries setting up and I think having one on the farm would be unusual and a great way to modernise what we do. It’d be unique and we could use lots of the resources we already have but it could take a long time to set up, purchase equipment and learn the ropes – that is something I am more than willing to do.’

Gwyneth

‘I love cooking and I’ve worked for others in hospitality and catering for ten years. I currently work part-time in a café but I don’t feel I could go back to full-time hours as I need some flexibility around my family. I want to make products at home that I can sell to delis and cafés in the area and at weekends at farmers’ markets and food fairs a little further afield.’

Julia

‘I live with my parents in an area where our local shop and Post Office are threatened with closure. This would mean my family and other local residents having to make a long and difficult journey to reach the next nearest Post Office branch or to buy daily supplies as public transport is so infrequent. I think that local residents could come together and run them as a community shop and I would like to be the person to lead on seeing if it is possible.’

Dafydd

‘My wife, Ffion, and I live on our family-run 140 acre sheep farm with our two children. We have three lovely traditional stone buildings on the farm which are surplus to requirements within our modern farming business. I would like to bring additional income into the business by restoring them to their former glory and letting them out as holiday lets.’

Gwenllian

‘I teach part-time. I have recently established a link with a local international corporation and realise that instead of the traditional type of language course, what they really seem to need is very tailored, ‘quick fix’. Basic language skill training and cultural briefings to prepare them for their business trips abroad. There is a lack of this kind of linguistic service in mid-Wales so my business idea is to develop a bespoke language service offering a range of different types of language support – from industry-based updateable, multi-platform, on-site translation and interpretation services.’

David

‘My business idea is to use my previous experience of making staircases for property developers and use it to establish my own company, designing and building bespoke staircases. I would use locally sourced, sustainably produced timber and work from a workshop located away from my home. I’ve worked self-employed before but this time it’ll be through choice, not necessity.’

If you are still a bit unclear about your business idea, it may help you to consider the seven sources of innovation identified by Peter Drucker (1985), whose writings have influenced the theory and practice of business, entrepreneurship, innovation and management for more than half a century.

2.2 Sources of innovative business ideas

Innovative ideas grow out of ordinary experiences and situations. Consider the suggestions below. Perhaps your business idea has developed from such a situation:

- past and present work and experience

- hobbies and leisure interests

- qualifications and studies

- new markets/uses for existing products

- solving a persistent problem

- research and development (R&D)

- patents, licences and research institutes

- invention

- opportunities from new technologies

- opportunities from economic/market changes

- changes in consumer behaviour

- complaints and irritations expressed by potential customers

- changes in rules and regulations

- imitating an idea from a different locality

- imitating an idea from a different industry

- improving an existing product

- films, TV and radio

- books, magazines and the press

- trade shows, exhibitions and conferences

- business and social networks

- family and friends.

Case study: Sources of innovation

David was pondering the list above and he concluded that while many of them could be included, his idea had been significantly influenced by the following:

- past and present work and experience – many years of practical experience as a joiner, making and fitting staircases. Taking on additional work to make staircases when the employer’s alternative was to source from further afield, at a greater cost to them.

- hobbies and leisure interests – creative work such as making bespoke items using his carpentry skills, which have been given as gifts to family and friends.

- research and development (R&D) – there have been a number of residential properties in the area that have been renovated in recent years, either for resale or to add aesthetic or monetary value during the property sales downturn. This has provided him with good, hands on research and development. He has provided stairs for commercial properties, and through this has become familiar with the specifications and with the necessary regulations and requirements.

- improving an existing product – staircases are something that homes and commercial properties of more than one story will always need. The basic design is the same. However, he can add and improve other qualities. Wood has not always been sustainably sourced, and local timber from sustainable sources is not being used. He could also look at using reclaimed wood whenever possible which means he could also add this as a selling point.

To have any chance of making it as a successful product or service in its chosen market, an entrepreneurial business idea has to find the right balance between two potentially conflicting forces:

- the need to be innovative (have something sufficiently new about it so that it is both attractive and competitive)

- the need to be viable (have sufficient resources, capabilities and potential customers to bring the product to market and achieve your financial objectives).

2.2.1 Generating innovation

Task 8: Generating innovation

The following table suggests situations that might generate innovation. Match the rural examples in this drag and drop exercise.

Foot and mouth

Situation 1: Unexpected happenings

Closure of village shop

Situation 2: Incongruous happenings

Processing wool for insulating material for packaging

Situation 3: A need for process improvements

Opening of a local farmers market

Situation 4: Changes in industry structure or market structure

An increase in the number of people over 65 living rurally

Situation 5: Demographics

Desire for more local food

Situation 6: Changes in perception, mood and meaning

Increased use of internet in rural communities

Situation 7: New knowledge

Two lists follow, match one item from the first with one item from the second. Each item can only be matched once. There are 7 items in each list.

Foot and mouth

Closure of village shop

Processing wool for insulating material for packaging

Opening of a local farmers market

An increase in the number of people over 65 living rurally

Desire for more local food

Increased use of internet in rural communities

Match each of the previous list items with an item from the following list:

a.Situation 7: New knowledge

b.Situation 3: A need for process improvements

c.Situation 6: Changes in perception, mood and meaning

d.Situation 5: Demographics

e.Situation 1: Unexpected happenings

f.Situation 2: Incongruous happenings

g.Situation 4: Changes in industry structure or market structure

- 1 = e,

- 2 = f,

- 3 = b,

- 4 = g,

- 5 = d,

- 6 = c,

- 7 = a

2.2.2 Further information

If you found this useful you might also want to:

- read Have you got a good idea?

- read Managing innovation

- or listen to Developing a new idea

2.3 Steps to success

The entrepreneur or business owner needs to have a defining belief that the idea will work and sufficient energy to drive it to be ready to launch on the defined market. Sometimes the finance required comes from personal funds, sometimes from grants and sometimes from banks, venture capitalists or other sources of funding.

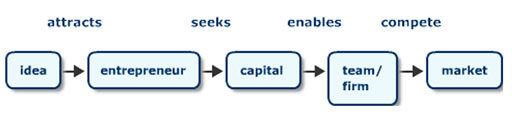

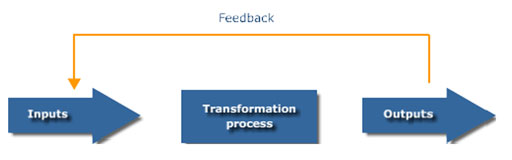

Flow chart describing the journey from idea to market. Idea attracts entrepreneur who seeks capital which enables the team/firm to compete in the market.

Wherever the capital is coming from it is important to be clear what the goals are in the short and longer term. If the funds are coming from personal or family sources you may not require a formal business plan, more a convincing conversation. However, it is best practice, wherever the finance comes from, to have some form of business plan – a plan that has clear goals that map out your route to success.

Your goals need to be SMART to be helpful.

- Specific

- Measurable

- Achievable

- Resource-related

- Timed.

For example, ‘I want to have a business that provides me with a good source of income’ sounds fine initially, but what is ‘good’? For some, an income of £10,000 would be fine, while others may require £50,000 or £100,000.

A SMART goal might be: ‘In two years time (timed) I will have a turnover of £500,000 (measurable and specific) with a 20 per cent profit margin (measurable)’.

It can be a matter of judgement whether the goal is achievable, which will depend on your market and starting position. Ensuring that the goal is ‘achievable’ does not mean it has to be soft or easy to achieve; it needs to be challenging, too.

When you work for someone else, the goal needs to be agreed with your manager; when you are the company owner the resources required need to be specified and need to be agreed with your board of directors, the bank manager, your family, and your staff where appropriate.

Task 9: Defining the business goals

- Think about where would you like your business to be in 12 months’ time. You will refine these goals as you work through the course and you gather more information to inform them. These short-term goals will inevitably be described in greater detail than those covering a longer time period.

- Now write down your goals for your business in three to five years’ time.

- Check that they are SMART

- Share your goals with other entrepreneurs in your local networks.

Along with the clear statement of your business idea, this is the first step to building your plan. This information will be required in your BPPR. It defines the strategic direction you will be following – but more about that to follow.

2.4 Company structure

One of the decisions you will be faced with is how to structure your business. This means the legal structure not the organisation structure.

If you are planning a commercial company, there are the following legal forms to choose from:

- sole trader

- partnership

- limited liability partnership

- limited company

- franchise

- social enterprise.

An overview of legal structures is available at Business Wales. It clearly explains the different legal forms. For further advice on this please contact your accountant or adviser.

The Welsh Government agenda has focused on ‘communities’ in recent times, with funding to support the establishment of a range of ‘non profit’ enterprises, community companies, social enterprises, charities, or community interest companies. We alluded to the growing importance of these organisations at the start of the course and also pointed you towards a range of support and advice services.

In setting up one of these you (and your community) will need to consider exactly the same things as any private or for profit enterprise; demand, financial viability, skills and capacity, and how to secure funding. However, as these are often publicly regulated bodies they have complex legal structure and you should contact one of the organisations listed in Links to get appropriate advice.

2.5 Environmental scan

The environment around you and how it is changing will influence the chances of your business succeeding. It is important to consider what factors are important and to understand how they influence your chances of success. The period since World War Two has seen unprecedented change and advances throughout the world in five key areas – societies, technologies, economic development, the environment and political systems and regulations. We refer to these areas as STEEP factors, and the pace of change in them has intensified in most parts of the world in recent years. Find out how an entrepreneur used STEEP in an audio track, Entrepreneurial Opportunities. This draws on a suite of resources exploring entrepreneurial opportunities which are featured throughout the course.

Sources of major change arising from STEEP factors

Social

- Ageing populations in most of the industrialised world

- Growth in mass migration and refugee populations

- Challenges to welfare provision and educational systems

- Changing consumer needs and wants.

Technological

- Speed and capacity of communication

- Moore’s Law (data capacity of computer chips doubles every 18 months)

- Increased consumer sophistication due to widespread use of computers and the internet

- New mobile and wireless communications applications

- Biological and genetic discoveries and applications.

Economic

- Integration of world financial markets

- Rise of BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India and China) as new world economic powers

- Relations between Euro and US dollar

- Dominance of ‘free-market, free-trade’ model

- Fast and increasingly transparent access to information

- Reduction in transaction costs.

Environmental

- Climatic change

- Genetically modified crops and produce

- Increased risk of epidemics and disease (AIDS, BSE, SARS and so on) through more mobile human and animal populations

- Ecological damage; reliance on energy sources that are effectively non-renewable.

Political

- European Union

- World Trade Organisation

- Increased regulation

- Regional resurgence

- Ethnic conflict, nationalism and militant fundamentalism

- The changing position of the US as the only superpower and the increasing importance of China on the world stage.

These changes are far reaching and affect us all. Some of these will have given rise to the opportunity you now have.

Some of the most spectacular changes have been in the introduction of new technologies and applications based on them. For instance, the rapid and almost universal spread of information and communications technologies (ICT) in the form of computers, broadband, the internet, mobile telephony and the many other applications that derive from them has cut communications times and increased access to information to such an extent that global competition reaches into the most local and rural of economies. However, there are still issues around broadband access for some rural areas.

Overall, globalisation (the integration of worldwide financial, product, resource and services markets) has encouraged the growth of transnational businesses and world brands and also, paradoxically, of localisation (promotion of distinctive community, local and regional activities and identities).

Both of these opposing tendencies are reflected in consumers increasing identification with global brands but also by the resurgence of consumer interest in local products and locally sourced foods. Rural areas are increasingly woven into the national and global economy via the internet. While it may be that the internet allows rural enterprises to access wider markets, it also works the other way around; national and global brands are able to sell more easily into rural areas.

Consequently, even quite minor changes in any of the STEEP factors can influence local economies and open up significant business challenges and opportunities. Looking again at the common sources of new business ideas in Section 2.1, you can see that many of them result from changes in one or more of the STEEP factors.

These changes can also close down options and adversely affect existing businesses and future plans. In general terms, STEEP factor effects will vary according to how industries and markets are structured in different regions.

2.5.1 Case study: STEEP factors

Case study: STEEP factors

Which of the STEEP factors predominantly impact Gwenllian’s business idea?

All of the STEEP factors will influence Gwenllian, and the most influential draw from the economic, social, technological and environmental.

The social factor of changing customer demographic profiles (increasing migration of people across Europe’s porous boundaries), means that the business community has to constantly adapt and adjust the way that it operates locally, regionally and globally. This means that the language skills needed to respond will also be constantly changing. A bespoke, flexible language service to meet the needs of the different business sectors is therefore likely to be an increasingly attractive commercial offer.

This is reinforced by the economic factor of globalisation meaning that products are sourced and traded internationally and within ever tighter timeframes. A language service that can offer quick, efficient, university-standard tuition, designed around the particular commercial needs of the client, may mean the difference between securing and losing overseas contracts. The economic factor is therefore key for Gwenllian. It will open up a significant business opportunity for her.

Technological factors have both up and downsides in relation to increased consumer sophistication, due to the widespread use of computers, the internet and new mobile and wireless communications applications. Fortunately, for Gwenllian, she has experience of delivering supported distance learning through her University work and of using Skype and telephone to support her students. She also has experience of using materials on CD and is able to design and deliver tailored learning programmes on multi-platforms.

Nevertheless, she will need to keep up with the latest pedagogical developments in online and supported distance learning if she is to remain competitive. However, a very real challenge to the future expansion of Gwenllian’s business may be the highly variable access to (reasonable speed) broadband which continues to be a particular challenge in rural Wales.

An increasing awareness of environmental issues means that Gwenllian’s ability to deliver learning through a variety of means (face-to-face tuition, via Skype and telephone contact, and by multi-platform programmes) makes her business offer particularly attractive as it offers a very flexible environmental footprint. This flexibility is especially impressive in a rural context where public transport is inadequate and travel-to-study times uneconomical for businesses to support.

From a political perspective, Gwenllian’s business benefits from its low environmental footprint, its support of the Welsh Government’s aspirations for the knowledge economy, and its contribution to the development of a stronger global reach for the Welsh economy.

Task 10: STEEP factors

- Review the list of STEEP factors and consider which are most significant for your business idea.

- Conduct your own ‘mini-STEEP’ by looking at each of the five specified areas in your locality. Use the STEEP template.

- Share your STEEP list with other entrepreneurs in your local networks.

Discussion

David had some thoughts about his business.

| STEEP factor | Significance | |

|---|---|---|

| Social | The ageing population means more lifestyle migrants moving to the country who want to renovate old buildings or build from new. There is potential for business increase from that group. Young people have fewer opportunities available in the area and might want work experience. I might be able to take on an apprentice as a cost effective way to grow the business. | links to ageing population and changes to customers’ needs and wants, changes to education systems |

| Technology | I could have a website to show my staircases and advertise my joinery workshops. Clients now often expect to see 3D ‘mock ups’ on computer. I could learn how to use design software (the local college may have a course). | speed and capacity of communications, increased consumer sophistication due to internet and ICT penetration |

| Economic | As the economic climate improves the potential for my products could grow. There are fewer local timber merchants and joiners working from scratch, which means similar businesses have centralised to the cities. People looking locally has led to more high end opportunities from those looking for something different. | |

| Environmental | Using sustainable products is always an issue, as well as using things made locally. My timber will come from the local area where there is a re-plantation programme. I could also look at using reclaimed materials. I would ensure that my production methods and workshop run on an eco-friendly basis. | loose link to global warming |

| Political | I am not sure if there are any political influences, although there is a growing identification with our region within the UK. |

David has considered the global STEEP and taken a local perspective. He has seen how some of these factors have influenced his local environment. He knows a lot of the local trades people, and has a ‘best guess’ at the market based on his experiences. The nature of David’s business means that he is unlikely to export his product. Selling to locals may work in David’s favour, as he is offering a local product and service that nobody else is. If you are considering retailing a product you may choose only to sell locally. However, living locally does not mean you have to sell your product or service locally, although you may choose to use your area as a trial market, at least while establishing your product.

2.5.2 Further information

Something that might help you think things through as you explore those wider factors and their influences is this series of audio resources on Understanding Social Change.

2.6 Stakeholders

There are many different stakeholders in a business. The first people who often spring to mind are the financial stakeholders and they are indeed important, but ‘stakeholders’ can be defined much more broadly as the range of people who have an interest in the company.

Freeman (1984) defines stakeholders as ‘any group or individual who can affect or is affected by the achievement of the firm’s objectives’; Hill and Jones (1992) prefer to define stakeholders as ‘constituents who have a legitimate claim on the firm’.

Stakeholders are not just external agents. Your family can be key stakeholders, they might rely on the business, and you may want to ask them how the time you spend on your business affects them.

In the case of Gwenllian, her husband – who is a music producer – will help her in the production of her language materials. Using the home as the cooking premises means that Gwyneth’s family life will have to accommodate manufacturing processes. Without the backing of his family who own the farm buildings he wants to use and the farm he currently works on, Euan will not be able to get his microbrewery up and running.

Stakeholders could include banks, funding agencies (like grant awarding authorities), employees, customers, suppliers, shareholders (if appropriate), the local community, the state and those who share the environment.

Identifying stakeholders

Historically, stakeholders were individuals or organisations (including law courts sometimes) that held the money or stakes of a bet, wager or other contest. They were independent of the gamblers or contestants but very important to the outcomes. More recently, stakeholders are seen as ‘interest groups’ or ‘interested parties’ who may not be directly involved in a transaction but whose fortunes are influenced or even strongly bound to the activities of your organisation.

Some of the more common stakeholders of significance to small firms include:

- owners

- shareholders

- managers

- employees

- suppliers

- customers

- consumers

- creditors

- retirees/pensioners

- distributors

- landlords

- business services (legal, accounting and so on)

- local community

- customers’ local communities

- suppliers’ local communities

- fellow small firm owners

- network members

- national economy/society

- international economy/society.

Each company will have different stakeholders, and the strength of their power and influence will differ from situation to situation and over time.

Task 11: Stakeholders

Identify the stakeholders in your proposed business. You may choose to use the stakeholder template but do not be constrained by it.

If factors such as the environment or family are important stakeholders in your business then add them and/or delete one of the stakeholders designated in the template. Consider the list above for additional possible stakeholders. You can have as many as you feel appropriate.

Use the stakeholder demands template to record the demands or expectations of each of the stakeholders.

Share your thoughts about stakeholders with other entrepreneurs in your local networks.

2.6.1 Case study: Stakeholder analysis

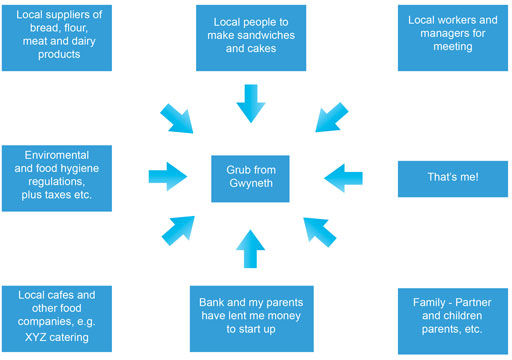

Let’s see how Gwyneth approached her stakeholder analysis:

Case study: Gwyneth

I used the basic diagram and tweaked it to fit my situation. I changed ‘shareholders’, which I won’t have initially as I plan to start up as a sole trader, to ‘family’, as they will have a big influence on the business and also their needs are my priority.

Centre box: Grub from Gwyneth. Surrounding boxes: Box: Local suppliers of bread, flour, meet and dairy products; Box: Local people to make sandwiches and cakes; Box: local workers and manager for meeting; Box: that's me!; Box: Family – partner and children, parents etc.; Box: Bank and my parents have lent me money to start up.; Box: Local cafes and other food companies, e.g. XYZ catering; Box: Environmental and food hygiene regulation plus taxes etc.

I could have included many more boxes, but I decided to concentrate on the stakeholders I felt were most important to me as I start up. I am sure the influence of each stakeholder will be different in 12 months’ time.

I found it quite daunting at first to think that all these people had an interest in and an influence on my new company. I started to work out what each stakeholder wanted from me and this meant that it became clearer what the impact of each stakeholder might be.

I decided to include myself as a stakeholder so that I could look at my needs alongside everyone else’s, to see if they were compatible.

| Stakeholder | Demands/needs | Power/influence – strong/weak? |

|---|---|---|

| Family | Children need to be dropped off and picked up from school Monday to Friday. They need my time in the evenings and weekends. Need to make up the drop in income from reducing my hours in the café – approx £250 per month. | Very strong |

| Me | To make a success of the company, earn some money and gain a sense of satisfaction while being close to my family, with the potential of giving up my café job completely. | Strong |

| Local companies | Good quality products that offer good value for money for them and for customers leading to return custom. Need to present my region well as a producer of high quality local products. | Strong |

| Suppliers | If my business works, I will start to place regular orders, and I will need to ensure I have the right amounts and have cash flow to make prompt payment. | Medium |

| Environmental health/food hygiene and government | Food is produced in clean and hygienic surroundings that are safe for me to work in, my family to be around and for customers. I need to keep accurate records of sales and turnover. | Strong |

| XYZ condiments | I will have competition – from major retailers but also from other local producers – we can help each other out sometimes maybe? | Medium |

| Bank | I will need to borrow money to cover the cost of industrial catering supplies and a stall for the markets and fairs. The bank expects a reasonable rate of return on their investment and for me to make regular payments. | Medium |

| My parents | They have given me some money towards my first set of jars and labels. While there is no current pressure, I would like to give them their money back at some stage – they want me to succeed. They also provide childcare at weekends and during school holidays. | Medium |

I marked how strong the demands of each stakeholder are on me, which helped me see which to prioritise.

I wasn’t sure about the power of my parents as they are very reasonable, but should they stop helping with the kids they would be very powerful indeed! I will need to think about how my business and family life can adapt to each other over time, should my business become successful. I can’t always guarantee my parents will have the good health or time to help with childcare – while it is a little stronger than ‘goodwill,’ I don’t think relying on goodwill is a way to operate a professional business!

That made me realise that demands change and the power of each stakeholder can change over time. I guess I need to keep an eye on that as my business develops…

Your business plan must recognise the needs of each of these stakeholders. You can see that often their needs are conflicting, for example, the needs of workers to have a good rate of pay and the needs of local firms to have sandwiches at as low a price as possible. Running a business is about balancing these conflicting interests to achieve a compromise that is acceptable to as many stakeholders as possible.

2.7 Competitive advantage

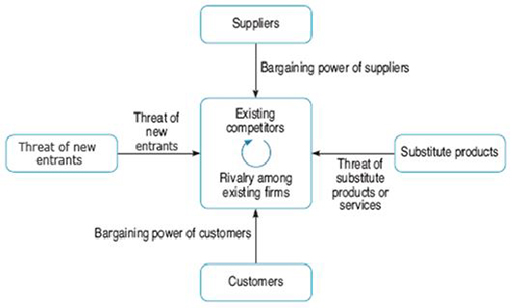

Michael Porter (1998) has an international reputation for his work around creating competitive advantage. His analysis of the impact of external competitive pressures or forces provides a useful framework to consider the types of forces and relationships between companies that influence local competition (and the sort of pressures that a new entrant company can face).

Porter sees the competitive pressures on a given industry in terms of ‘five forces’ – in addition to the central struggle with existing competitors, there are new competitors entering the market, arguments with suppliers over the costs of inputs and persistent downward pressures on selling prices from customers. All these, except sometimes new entrant competitors from outside, are visible. Less obvious are the competitive forces that come directly and indirectly from consumers and customers when they turn to alternative or substitute ways of meeting their needs, for example internet-based travel services versus high street travel agents.

The five forces also represent areas where entrepreneurs can spot opportunities for innovation that offer a decisive competitive advantage. Looking at the competitive environment in this way can help us understand how the STEEP factors are affecting our customers.

Centre box: Existing competitors, Rivalry among existing firms; Box above: Suppliers; arrow to centre: Bargaining power of suppliers; Box right: Substitute products; arrow to centre: Threat of substitute products or services; Box below: Customers; arrow to centre: Bargaining power of customers; Box to left: Threat of new entrants; arrow to centre: threat of new entrants.

Task 12: Competitive advantage analysis

Complete a five force analysis for your proposed business using the Five force analysis template.

Indicate if you think the bargaining power is low, medium or high in each case.

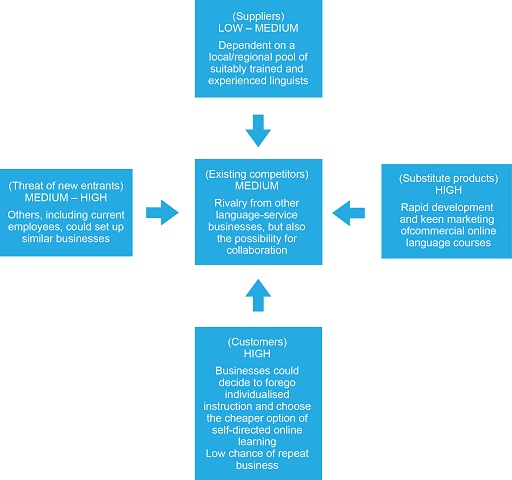

Discussion

Boxes 1–4, with arrow pointing to box 5 in the centre. box 1: (Suppliers), LOW – MEDIUM. Dependent on a local/regional pool of suitably trained and experienced linguists. box 2: (Substitute products). HIGH. Rapid development and keen marketing of commercial online language courses. box 3: (Customers) HIGH. Businesses could decide to forego individualised instruction and choose the cheaper option of self-directed online learning Low chances of repeat business. Box 4: (Threat of new entrants) MEDIUM–HIGH. Others, including current employees, could set up similar businesses. Box 5: (Existing competitors) MEDIUM. Rivalry from other language-service businesses, but also the possibility for collaboration.

From this analysis it is clear that while Gwenllian’s business idea is reasonably unique, she is entering a potentially competitive area. She will need to pay particular attention to how her company builds a niche and customer base in order to protect her business idea and succeed.

2.8 What is a strategy?

There are many definitions of strategy:

- Chandler (1962) ‘The determination of the basic long-term goals and objectives of an enterprise, and the adoption of courses of action and the allocation of resources necessary for those goals.’

- Andrews (1971) ‘Every business organisation, every sub-unit of an organisation and even every individual (ought to) have a clearly defined set of purposes or goals that keep it moving in a deliberately chosen direction and prevent it drifting in an undesired direction.’

- Porter (1985) ‘A process of analysis that is designed to achieve the competitive advantage of one organisation over another in the long term.’

- Henderson (1984) ‘To enable an organisation to identify, build and deploy resources most effectively towards the attainment of its objectives.’

Whichever definition strikes a chord with you, they all emphasise that strategy is about the long term:

- clear vision through goals

- understanding your external environment to ensure the goals are realistic

- appropriate allocation of resources to the tasks that will most likely help the company achieve its strategy implementation.

As the owner of a small business, it is inevitable that you will get involved in all aspects of the business, particularly at start up.

It is important to distinguish between operational and strategic thinking. Operational thinking relates to those tasks or activities that characterise the day-to-day working of the company. This could be anything from making practical, stylish staircases (David), producing some delicious and unique sandwich relish (Gwyneth), drafting a marketing email (Dafydd), designing a language course (Gwenllian), or monitoring the purity of the water obtained from the farm well (Euan). The more efficiently these are completed the better it is, as the costs will be kept to a minimum and output of the company will be enhanced.

Strategic thinking looks at the business more holistically. It connects all the activities and considers how they relate to each other in achieving the overall objectives of the company. Strategic thinking questions how the tasks can be aligned, combined or performed differently to deliver something better. For a not-for-profit organisation ‘the fit’ between these aspects also needs to account for the ethos or wider goals of the organisation. Find more information about creating an ethical organisation.

Many small business owners are guilty of ‘working in the business not working on it’. It is easy to become so engrossed with meeting operational day-to-day requirements that there is no time left for any strategic, longer term thinking.

2.8.1 Case study: Operational versus strategic thinking

Read this short case study and think about the main issues facing Fiona.

Case study: Managing everything – and nothing

Fiona was excited when her father announced that he was going to retire and that she was to take over as general manager of the small chain of off-licences (retail outlets for alcoholic drinks) that he had founded. She had lots of ideas about expanding the business, the most important of which was the establishment of a wholesale business supplying clubs and restaurants.

The new business was successful – she had identified a useful market niche – and after a year its sales were better than forecast. But it was not yet making money, largely because the operating costs were above budget. It was essential to introduce an efficient stock control system, and she set about finding a suitable software package. There were a number of teething problems – it was constantly crashing and she was the only one able to operate it, so it took a lot of her time. The company needed to recruit a new driver and a new order clerk: it was important to get the right people, but interviewing and agreeing terms seemed to go on forever.

One of her ideas had been to provide an own-label service for restaurants, so that they could serve wine with their name on it, and this had proved very popular. She enjoyed designing the labels with her software package, which she tended to do in the evenings. It was also necessary to remove all the original labels and apply new ones – and they simply did not have the labour to do this, so she found herself spending most of her weekends labelling wine bottles.

The wholesale business had introduced a number of new customers, several of whom proved to be bad payers, so she was spending an increasing amount of time chasing debts.

Their price list had not changed for three years, and she knew that a number of their products were now significantly underpriced, but she simply had no time to update the list. And the new business was still not delivering a profit.

You can see that Fiona is focused on operational tasks. She is busy operating and sorting the stock control software and designing, removing and sticking labels. She is thinking operationally and not strategically. She is working ‘in’ the business rather than ‘on’ it. Strategic thinking would enable her to look at the complete picture and decide which activities lead to delivery of the company’s strategy. She would be able to see which processes could be combined or even abandoned. She would be able to allocate resources more effectively (more about resources in 4 Capabilities and resources), which would improve the chances of success for the company.

Setting some regular time aside to take a step back and reflect on your business will be very difficult at times but also very important to ensure you allow yourself time for some strategic thinking. Working with a mentor or advisor can help you do this. Often it is the business owners who feel they have the least time and the least need to have a mentor, who most need time and a mentor!

There are many times when there are just not enough hours in the day, particularly at the start of a new business when you seem to be doing everything yourself. Time spent with an external experienced advisor or mentor can be likened to having a non-executive director for a larger company. They can see issues with fresh eyes and can help you consider the longer term view to get through the short-term operational pressures. They can also be a listening ear, a support and trusted friend.

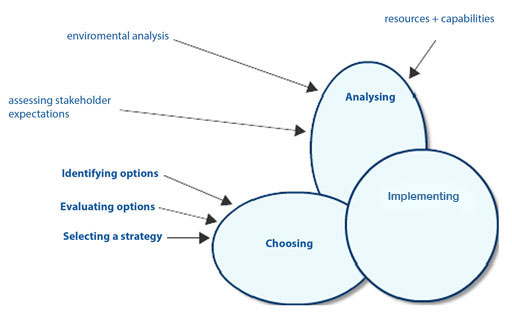

2.9 Formulating strategy

You have now examined the external environment and looked more deeply into how the STEEP factors have an impact upon your local market and how you can expect to relate to your suppliers and customers with knowledge of substitute products and new entrants. You have also completed some analysis.

You now need to think about your longer term options and select the best way to work in order to meet your objectives. You have to determine your strategy and then implement it.

Three overlapping circles: Analysing – resources and capabilities, environmental analysis, assessing stakeholder expectations; Choosing – identifying options, evaluating options, selecting a strategy; Implementing.

Many strategies are decided as the result of a thorough analysis, perhaps some research, and clear decision making. Many others emerge as a company grows or gets started. Neither route is wrong.

It is important to keep reviewing your strategy against results to check if it is working. Many things can change in the STEEP factors, which may give rise to the need to review the strategy, but it is important to give it time to work. Remember, a strategy is a long term plan – you cannot change it every week!

Developing and reviewing your strategy is an area where a mentor can be especially valuable. They can help you see the wood for the trees and ask the questions that can sometimes be hard to see when you are immersed in the day-to-day grind.

Task 13: Identifying your strategic options

- What options do you have that could deliver your objectives?

- List the pros and cons of each.

- What additional information do you require before you can decide?

You will need to use the outcome of this activity in your BPPR.

Share your thoughts with other entrepreneurs in your local networks.

Discussion

Case study: Euan

Euan’s business idea is to establish a microbrewery on his family’s farm.

He sees his options as:

- obtain permission to convert the existing unused farm buildings into brewing sheds (this may require a planning application)

- invest in machinery for the barley and hops preparation and brewing processes

- invest time and money in training to learn the skills of brewing

- concentrate on the unique selling points to market the beer

- use farm resources to provide ingredients, such as winter barley

- consider retail outlets, the possibility of off- sales on the farm via a shop, and mail order sales

- explore options for food tourism via brewery tours on-site.

In this example, not all the options are mutually exclusive. Euan needs some detailed information to help him decide. He needs to gather information about the extent of his investment in terms of the time it will take to purchase machinery and establish the microbrewery.

In assessing which route to market to take, he will need to take into account the resource constraints at the farm and the existing expertise within his family. As farmers, he and his parents are used to running a business, but there will be some key differences between farming and brewing.

Euan may have to negotiate reallocation of space on the farm, but this is probably not a strategic driver. By carefully reviewing his results against his chosen strategy, he will see if there is a need for more space (i.e. he will not know the answers to these questions until his business has started operating). If his business objective was to supply winter barley to other brewers, then changing the use of fields from grazing to growing areas may be a strategic decision.

Keep these strategic options in mind as you work through the rest of the course. You will add more information to your analysis as you progress. This will help you decide which strategic option is the best fit for your new company.

2.10 Summary

In this section you have:

- articulated your business idea and how it fits with your rural lifestyle

- set your SMART business goals for the next three to five years

- considered the most suitable company structure

- completed a mini-STEEP

- identified the stakeholders for your business and their strength of influence

- gained an understanding of your competitive environment through Porter’s five forces model

- reviewed the process of strategy formation and outlined the strategic options for your business.

Now open your BPPR (or download the template) and reflect on the activities completed in this section. Review the output from each activity and complete the three questions raised in Section 1 of the BPPR, which require you to pull out the most important aspects of your thinking to date.

3 Customers, markets, competition and pricing

Learning outcomes

At the end of this section you will be able to:

- identify the customer decision-making process

- state the difference between types of customer and consumer

- recognise the market research process and the importance of different types of information

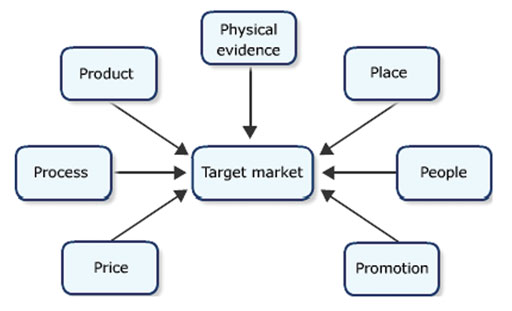

- identify the four Ps – four Cs marketing mix model

- know how ‘place’ can affect a rural business

- identify factors affecting pricing decisions

- identify some low-cost ideas for promotion.

3.1 What is a customer?

Whatever your business, product or service, you will need customers. It can feel like there are so many things to do when you start a company. Very often a great deal of time is spent perfecting the product, be it a beer or a pot of jam, and no time is left really to understand your customers and potential customers.

There are a number of different types of customers:

- customers who are also consumers – for example, a restaurant or café

- customers who buy for others (consumers) – for example, local government buying-in services from a social enterprise

- customers who buy for others (businesses) – for example, utility warehouses that buy energy for other companies

- other businesses – for example, a company that develops a service for other companies to use.

Task 14: Identifying your customers

Think about the groups of people who will be your customers.

- Will you be selling mainly to consumers, other businesses or government bodies?

- Will you be selling mainly to consumers, intermediate customers or to buyers or purchasing units of larger organisations?

- Do you have ways of classifying the key purchasing decision makers you will have to influence in your industry (or more particularly, in your business)?

Share your thoughts with other entrepreneurs in your local networks.

Discussion

It is not always a case of there being just one type of customer or another.

Case study: Gwyneth

Gwyneth may sell to customers who are consumers. This means they would buy pots of jam, chutney or preserve and eat them themselves.

She may also sell to a retail manager who buys to sell in their shop to their customers. The manager will not consume the food at all.

Gwyneth may at some point in the future expand her business and also sell to a purchasing manager or buyer for online sales.

It is important to think one or two steps beyond the immediate customer/consumer.

Gwyneth needs not only to think about her immediate buyers but also who will have a key influence in enabling her to supply to a wider customer base.

3.1.1 Customer needs

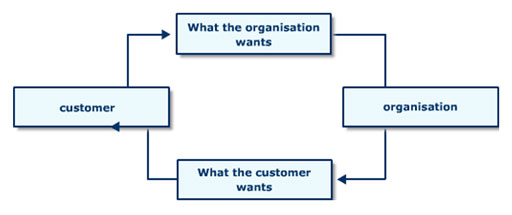

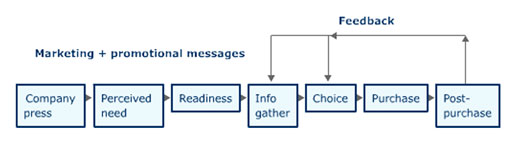

The basic process that a buyer travels through is the same, irrespective of the product or service being purchased. However, it may be prolonged and completed more rigorously if the product is of high value. There is a basic exchange process between customer and organisation.

Boxes linked in a circle with arrows: What the organisation wants; Organisation; What the customer wants; Customer.

Task 15: Customer needs

Consider a product or service that your company will provide.

Describe the exchange relationship with a customer by filling in the boxes in the Customer needs template.

You might like to consider a number of different customers – you may find that their needs are quite different.

Share your thoughts with other entrepreneurs in your local networks.

Discussion

Case study: Gwyneth