13.1 The resilience of oral storytelling

There is a need to qualify the term ‘oral’. As printing developed in Scotland, and literacy grew, a market opened up for cheap versions of songs and stories. These booklets were effectively folded sheets of print. The storytelling ones were often known as chapbooks and the ones with sung ballads as ‘broadsides’. These did not displace oral communication but they did feed into it.

The minority of the population who could read might memorise and then share these narratives, while many of the pedlars or chapmen who hawked them around Scotland performed their contents as a form of sales pitch. Some travelling professions such as tailors also became known for their storytelling abilities. In this way, Scots language material was sustained through print and oral memory.

Something that survives only by oral transmission is, by definition, impossible to find before the onset of modern recording technologies. We do, however, have some precious records of oral performance. The following example comes from the memories of Charles Kirkpatrick Sharpe from Hoddam in Dumfriesshire, written in later life in Edinburgh. Sharpe was a friend of Robert Chambers, who used Sharpe’s manuscripts in his Popular Rhymes and Traditions of Scotland [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] (1870).

This book went through successive editions as Chambers went on collecting, but Sharpe’s memories of his Nurse Jenny’s storytelling were a valued element from the first edition of 1826 onwards.

Cultural links

In collecting and sharing Nurse Jenny’s stories in this way, Sharpe and Chambers were very much at the forefront of cultural developments happening across Europe.

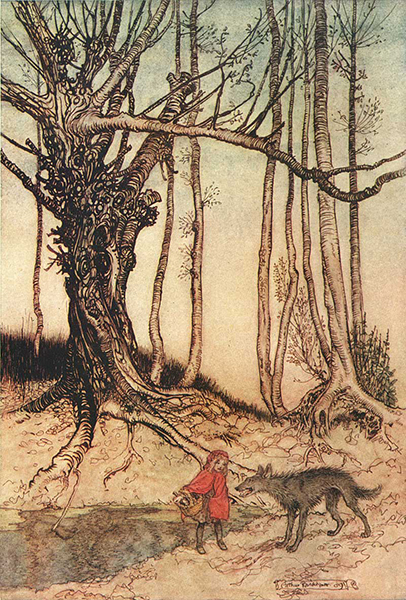

In the early 19th century, many scholars of language and culture, such as the famous Brothers Grimm in Germany, had begun to recognise that folklore and the traditions of the ‘common’ people were the essential part of every culture. This came as a consequence of the rise of Romanticism during the 18th century, which had revitalised interest in traditional folk stories. To the Grimms and their colleagues, it represented an ‘uncorrupted’ form of national literature and culture, free from the influence of the ruling classes.

Like the Brothers Grimm, who collected and published folk tales and popularised traditional oral tales during the 19th century, Sharpe recoded the stories his Nurse Jenny had told him, including the way in which she made traditional stories and tales her own, adding embellishments, linking them to her local context – and last but not least – using her mother tongue, Scots, to convey them.

Activity 4

Part 1

Now work with an extract from Sharpe’s memories of his Nurse Jenny’s storytelling. To convey this oral tradition in the Scots language as authentically as possible, we want you to work with an audio recording rather than a written version of one of Jenny’s fairy stories.

Before beginning to listen, we suggest you look up the following words in the DSL, or you might also want to try the Online Scots Dictionary, as knowing the meaning of these words will help you follow the story better.

- caad (v.)

- kent (v.)

- aweel / weel (adv./adj.)

- weel sookit (adv./adj.)

- gae / gaes (v.)

- grys (n.)

- soo (n.)

- wolron (n.)

- moudiewart (n.)

Part 2

First of all, listen without reading the transcript and take some notes on what you think Nurse Jenny’s story is about.

As a second step, listen again while reading the transcript and compare your understanding with your notes.

Transcript

I never saw ane myself, but my mother saw them twice- ance they nearly droned her, when she fell asleep by the water-side: she wakened wi them ruggin ay her hair, and saw something howd down the water like a green bunch o potato shaws.

Memory has slipped the other story, which was not very interesting

My mother kent a wife that lived near Dunse- they caad her Tibbie Dickson: her goodman was a gentleman’s Gairdner, and muckle frae hame. I didna mind whether they caad him Tammas or Sandy- for his son’s name, and I kent him weil , was Sandy, and he-

Chorus of children: Oh never fash aboot his name, Jenny

Hoot, ye’re aye in sic a haste. Weel, Tibbie had a bairn, a lad bairn, just like ither bairns, and it thrave weel, for it sookit weel, and it & (Here a great many weels). Noo Tibbie gaes se day to the well to fetch water, and leaves the bairn in the house by itsel: she couldna be lang awa, for she had but to gae by the midden, and the peat-stack, and through the kailyaird, and there stood the well- I ken weel aboot that for (Here another long digression).

Aweel as Tibbie was comin back wi her water, she hears a skirl in her house like the stickin o a gryse, or the singin o a soo: fast she rins and flees to the cradle, and there I wat she saw a sicht that made her heart scunner. In place o her ain bonny bairn, she fand a withered wolron, naething but skin and bane, wi hands like a moudiewart, and a face like a paddock, a mouth frae lug to lug, and twa great glowrin een.

Answer

This is a model answer. Your answer might be different.

Nurse Jenny’s fairy tale is about Tibbie Dickson, a mother who goes to fetch water from the well, and who, when coming home, finds that the fairies put a spell on her child, who has changed from a sweet looking boy to a skinny scoundrel with a huge mouth and scary eyes.

Language note

Chambers was a publisher based in London and Edinburgh which points to the fact that their publications were meant for an audience beyond Scotland. This had an impact on the way in which Scots language was represented in their publications.

Whilst it is likely that some aspects of the Scots pronunciation have been toned down in the written version in order to provide anglicised spellings sufficient to make the passage readable for both Scots and English speakers, Nurse Jenny’s story is rich in Scots vocabulary, and patterns of word order such as ‘I didna mind whether…’; or ‘she couldna be lang awa…’, which in English would be “I cannot remember whether…” or “she couldn’t have been away for long…”

You might want to find other examples of typical Scots tense forms of verbs and word order and comment on the Scots language features.

However, the principal point of interest is Charles Kirkpatrick Sharpe’s recall of Jenny’s tale is its narrative style. This abounds in digressions linking personal memories and anecdotes to the main fairy tale. By weaving the fairy story into the everyday reality of herself and her audience, Jenny cleverly establishes a new platform of credibility on which the fairy world of fantasy can operate with the same credibility as going to the peat-stack. This unity of perspective is carried by the same use of language throughout, namely Scots.

Here is another example of Jenny’s narrative art, displaying an assured narrative flow, and a mastery of oral Scots vocabulary and idiom, the story of Whuppitiestourie.

The strange and questionable land of ‘Kittlerumpit’ has been anchored in Jenny’s own experience – and now that of her audience – through association with the real life episodes. We are ready to go wherever the tale takes us in Jenny’s accomplished storytelling flow. As it unfolds the tale is ‘Whuppitiestourie’ a distinctively Scots version of the international fairy story ‘Rumpelstiltskin’.

Activity 5

Part 1

As with the previous fairy tale, before listening, look up the following key words which will help your understanding of the Scots language used by Nurse Jenny:

- lily (adj.)

- gerse (n.)

- ane (adj., pron.)

- clatter (v.)

- vaguing (adj., n.)

- cleikit (v.)

- duleful (a.)

- limmer (n.)

- fendin / fend (v., n.)

- farra / farrow (adj.)

- listed (v.)

Part 2

Now listen to and enjoy Nurse Jenny’s version of Rumpelstiltsken. The use of song or verse to assist the story is both a sign of antiquity in the material but also of narrative skill in using different kinds of rhythm for variety and effect.

Humour is deployed throughout, whether applied to fairyland or the everyday world. These traditional stories are more than entertainment but without entertainment value, humour and suspense, they cannot function. Nor would they survive.

- a.What explanations does Nurse Jenny give as possible reasons for the disappearance of the goodman o Kittlerumpit?

- b.What was the one consolation for the gudewife o Kittlerumpit after her husband disappeared?

Transcript

Listen

I ken ye’re fond o clashes aboot fairies, bairns; and a story anent a fairy and the gudewife o Kittlerumpit has joost come intae my mind; but I canna very weel tell ye noo whereabouts Kittlerumpit lies. I think it’s somewhere in amang the Debatable Grund; onygate I’se no pretend to mair than I ken, like aabody noo-a-days. I wuss they wad mind the balant we used to lily langsyne:

Mony ane sings the gerse, the gerse,

And mony ane sings the corn;

And mony ane clatters o bold Robin Hood,

Ne’er kent where he was born.

But hoosoever, about Kittlerumpit: the goodman was a vaguing sort o a body; and he gaed to a fair ae day, and not only never came hame again, but never mair was heard o. Some said he listed, and ither some that the wearifu pressgang cleikit him up, though he was clothed wi a wife and a wean forbye. Hech-how! That dulefu pressgang! They gaed aboot the kintra like roaring lions, seeking whom they micht devoor. I mkind weel, my auldest brither Sandy was aa but smoored in the meal-ark hiding frae thae limmers. After they war gane, we pu’d him oot frae amang the meal, pechin and greetin, and as white as ony corp. My mither had to pike the meal oot o his mooth wi the shank o a horn spoon.

Aweel, when the goodman o Kittlerumpit was gane, the goodwife was left wi a sma fendin. Little gear had she, and a sookin lad bairn. Aabody said they war sorry for her; but naebody helpit her, whilk’s a common case, sirs. Howsomever, the goodwife had a soo, and that was her only consolation; for the soo was soon to farra, and she hopit for a good bairn-time.

Model

I ken ye’re fond o clashes aboot fairies, bairns; and a story anent a fairy and the gudewife o Kittlerumpit has joost come intae my mind; but I canna very weel tell ye noo whereabouts Kittlerumpit lies. I think it’s somewhere in amang the Debatable Grund; onygate I’se no pretend to mair than I ken, like aabody noo-a-days. I wuss they wad mind the balant we used to lily langsyne:

Mony ane sings the gerse, the gerse,

And mony ane sings the corn;

And mony ane clatters o bold Robin Hood,

Ne’er kent where he was born.

But hoosoever, about Kittlerumpit: the goodman was a vaguing sort o a body; and he gaed to a fair ae day, and not only never came hame again, but never mair was heard o. Some said he listed, and ither some that the wearifu pressgang cleikit him up, though he was clothed wi a wife and a wean forbye. Hech-how! That dulefu pressgang! They gaed aboot the kintra like roaring lions, seeking whom they micht devoor. I mkind weel, my auldest brither Sandy was aa but smoored in the meal-ark hiding frae thae limmers. After they war gane, we pu’d him oot frae amang the meal, pechin and greetin, and as white as ony corp. My mither had to pike the meal oot o his mooth wi the shank o a horn spoon.

Aweel, when the goodman o Kittlerumpit was gane, the goodwife was left wi a sma fendin. Little gear had she, and a sookin lad bairn. Aabody said they war sorry for her; but naebody helpit her, whilk’s a common case, sirs. Howsomever, the goodwife had a soo, and that was her only consolation; for the soo was soon to farra, and she hopit for a good bairn-time.

13. Introductory handsel