13.2 Humorous folk tales in Scots

Humorous folk tales such as those mentioned in section 13.1 continued to be told through the 20th century, mainly in rural areas, and among Scotland’s Travelling people. Here is a good example told by Traveller storyteller Betsy Whyte. This is a comic variant on the folk tale The Man or Woman Who Had No Story to Tell.

This tale is based on the idea that at a social gathering everyone attending would be supposed to ‘do a turn’ – tell a story, sing a song, play music or recite a poem. Failing that some adventure or mishap follows – involving, in this case, a sex change – so ensuring that in future the person concerned will have a story to tell!

One example of such a story is the tale of Jack the cattleman who was changed into a beautiful girl then back into himself, which you can listen to here [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] .

However, this kind of do-it-yourself entertainment was not restricted to rural gatherings or Highland ceilidhs. It was also a feature of Scottish urban life, particularly from the 19th century when large numbers of poorer people migrated to cities in search of work. There were what might be termed ‘kitchen ceilidhs’ or ‘backgreen’ concerts and regular sessions in the back rooms of pubs, which became known as ‘speakeasies’.

In addition, there was a vigorous tradition of street entertainment, interacting with popular theatre performances in temporary venues known as ‘penny gaffs’. More middle class groups including church congegrations also organised paying concerts which used Scots stories, sketches and songs in more ‘respectable’ surroundings.

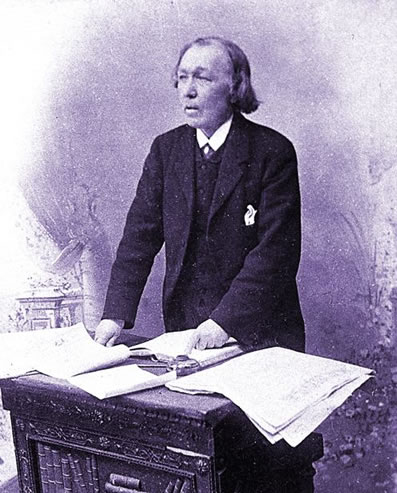

A poet and tragedian of Dundee, has been widely hailed as the writer of the worst poetry in the English language. A self-educated hand loom weaver of Irish descent, he discovered his discordant muse in 1877 and embarked upon a 25 year career as a working poet, delighting and appalling audiences across Scotland and beyond.

We know a bit about the lives of some of the performers who operated in these venues. William McGonagall’s performance poetry should be understood in the context of the penny gaffs, while William Houston was a successful performer on the politer circuits.

In Edinburgh, the Victorian writer James Smith (1824-1887) wrote for the popular entertainers. We are fortunate to have an example of his theatrical work, discovered in the Edinburgh Central Library and re-adapted for the stage by the modern playwright Donald Campbell, who was born in Edinburgh’s Cowgate, and who described it as a ‘found play’ (2007, p. 1).

This play, Nancy Sleekit (2007), is the story of an oft widowed and – if she is to be believed – much-put-upon lady, whom we meet first in mourning. The on-the-page text is a mixture of Scots and English spelling, reflecting James Smith’s, and then Donald Campbell’s editing, to ensure that the written version is comprehensible.

But the Scots strongly signals to a performer that every word and phrase will be shaped by Scots pronunciation and speech patterns.

Activity 6

Part 1

From the Nancy Sleekit extract below, identify a few English words included by the authors to ensure the written version was comprehensible for many, that you have seen the Scots spelling of in previous sections of this course.

I prefer weddings! That’s the even-doun truth, ye may think o’t what you like. I’m nane o yer mealy-moothed hypocrites that say ae thing and think anither – like a wheen o sour-faced auld fuffers that I ken. I like being mairriet, I’ve aye likit being mairriet. Nane o yer single blessedness for me!

Oh, it’s no that matrimony’s been sic a bonny bed o roses, that I likit the mairiet state sae weill – for God knows I had plenty to try me- by nicht and by day, for mony a year. I’ve been made a fair ringan devil when there was nae deevil in my heid –for my termpers’s as sweet as sugar candy when I get everything my ain way.

She sits down and takes another drink. She then opens the vanity case and takes out a cutthroat razor.

My first man was Tammie MacWiggie, a razor-faced, fiery-nosed barber, that I thocht was a perfect saint upon earth during our courtship – but there was never a greater draw-my-leg in creation. D’ye think he wad look at the very colour o blue ruination afore we were mairrit? No him! He preached and lectured on the horrors o drink in sic an eloquent manner that it actually made me greet! ... Sae I gied him my hand and my hairt, in aa the gowden prime o maidenly innocence. I fair thocht myself in Paradise – for the first fortnicht!

Answer

This is a model answer. Your selection of words might be different.

- sour - soor

- for - fir

- to - ta/tae

- devil - deil

- myself - myself/masel

Part 2

Now listen to the extract from Nancy Sleekit you have worked with in Part 1. You might want to read it out loud alongside the recording to practise your spoken Scots.

Transcript

Listen

I prefer weddings! That’s the even-doun truth, ye may think o’t what you like. I’m nane o yer mealy-moothed hypocrites that say ae thing and think anither – like a wheen o sour-faced auld fuffers that I ken. I like being mairriet, I’ve aye likit being mairriet. Nane o yer single blessedness for me!

Oh, it’s no that matrimony’s been sic a bonny bed o roses, that I likit the mairiet state sae weill – for God knows I had plenty to try me- by nicht and by day, for mony a year. I’ve been made a fair ringan devil when there was nae deevil in my heid –for my termpers’s as sweet as sugar candy when I get everything my ain way.

She sits down and takes another drink. She then opens the vanity case and takes out a cutthroat razor.

My first man was Tammie MacWiggie, a razor-faced, fiery-nosed barber, that I thocht was a perfect saint upon earth during our courtship – but there was never a greater draw-my-leg in creation. D’ye think he wad look at the very colour o blue ruination afore we were mairrit? No him! He preached and lectured on the horrors o drink in sic an eloquent manner that it actually made me greet! ... Sae I gied him my hand and my hairt, in aa the gowden prime o maidenly innocence. I fair thocht myself in Paradise – for the first fortnicht!

Model

I prefer weddings! That’s the even-doun truth, ye may think o’t what you like. I’m nane o yer mealy-moothed hypocrites that say ae thing and think anither – like a wheen o sour-faced auld fuffers that I ken. I like being mairriet, I’ve aye likit being mairriet. Nane o yer single blessedness for me!

Oh, it’s no that matrimony’s been sic a bonny bed o roses, that I likit the mairiet state sae weill – for God knows I had plenty to try me- by nicht and by day, for mony a year. I’ve been made a fair ringan devil when there was nae deevil in my heid –for my termpers’s as sweet as sugar candy when I get everything my ain way.

She sits down and takes another drink. She then opens the vanity case and takes out a cutthroat razor.

My first man was Tammie MacWiggie, a razor-faced, fiery-nosed barber, that I thocht was a perfect saint upon earth during our courtship – but there was never a greater draw-my-leg in creation. D’ye think he wad look at the very colour o blue ruination afore we were mairrit? No him! He preached and lectured on the horrors o drink in sic an eloquent manner that it actually made me greet! ... Sae I gied him my hand and my hairt, in aa the gowden prime o maidenly innocence. I fair thocht myself in Paradise – for the first fortnicht!

When the piece was revived for the modern stage in 1994, Nancy was played by Anne Louise Ross, a well-known Scots actress, whose natural command of Scots idiom informed her interpretation of the text throughout. Though such re-staging can only throw an experimental light on the past, the evidence clearly suggests that a rich urban Scots was the default linguistic medium for popular urban entertainment in the 19th century.

And this accords with the printed evidence from chapbooks, broadsides and the weekly newspapers, whose circulation increased steadily with each decade from the 1800s onwards.

As the monologue in the play develops, Nancy is revealed as a serial disposer of inconvenient husbands. In the process, she sends up traditional Victorian pieties of house and home, and gender stereotypes, reinforcing the sense that oral Scots continued as a vehicle for social satire.

Religion, romantic sentiment, and the trappings of respectability, which were supposed to be the essence of Scottish Victorian culture, are resolutely undercut by Nancy’s sly and reductive realism in the play. You’ve seen an excellent example of this realism concluding the extract from Activity 6: ‘Sae I gied him my hand and my hairt, in aa the gowden prime o maidenly innocence. I fair thocht myself in Paradise – for the first fortnicht!’

13.1 The resilience of oral storytelling