13.3. Music halls and the dominance of English

Penny gaffs and speakeasies were very popular but their success also sowed the seeds of their undoing. The city authorities began to impose licensing restrictions, and this led to the growth of larger, better organised, venues – the music halls. Initially the audiences for the music hall acts were local and the already successful staples of Scots comedy such as over-kilted Highlanders, interfering spinsters and village worthies continued to provide an outlet for satiric representations of Scottishness.

But the music halls were paying venues which attracted a much wider clientele than the non-paying speakeasies, and the business acumen of their managers led to organised touring circuits, including overseas tours. The foundation of the hugely successful international business of Variety Theatre had been laid.

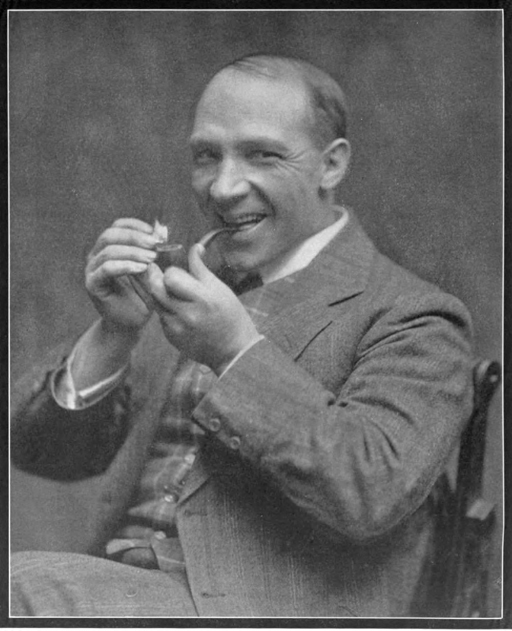

Performers such as W.F. Frame were among the first to make this transition from the local speakeasy to an international stage. Here he is in 1898 opening a show for emigrant Scots in the Carnegie Hall in New York with a verse monologue ‘Brither Scots, When Freens Meet He’rts Warm’ (Frame, 1905 p. 93–94):

I’m here the nicht, faur frae the shore,

Faur frae the land we a’ adore-

The land that gied oor faither’s birth,

The dearest land on a’ the earth;

Whaur bonnie grows the purple heather-

Whaur some o’ us were boys together,

The land o’ yours, the land o’ mine;

An you revere it, weel I ken,

Scottish women, Scottish men.

Who ne’er forget, though great or sma’,

The freens in Scotland far awa’.

Auld Scotland’s sons frae ower the seas-

Men frae rocky Hebrides;

Men frae the mountain and the glen;

Men wha can wield the sword and pen’

Frae the Hielans, Lowlands, don’t forget

That Scotland is auld Scotland yet.

That land that’s faur across the wave,

The land whaur there is many agrave;

Graves that haud both yours and mine-

Freens o’ oor youth, o’ sweet lang syne.

Activity 7

In this activity you will consider how the Scots language of W.F. Frame’s monologue has changed in comparison with the quotes from earlier storytelling in Scots language, which you have studied previously in this unit.

Read the monologue ‘Brither Scots, When Freens Meet He’rts Warm’ and pay particular attention to:

- the perspective on Scotland displayed here

- the amount of Scots vocabulary used

- the use of rhyme for performance purposes.

Then write a short summary of your findings.

Answer

This is a model answer. Your answer might be different.

It is clear that Frame is looking at Scotland – together with his audience – from a distance. The perspective on Scotland has become hazy, stereotyped but also misty eyed and romanticised. The Scots language content has thinned and English language is taking on an even more prominent role. This might have been done in an effort to ensure the monologue would be understood by the New York audience.

Yet, this had an impact on the role Scots played in the monologue overall – it became somewhat decorative, whereas English takes over as a structural element. This can be seen for example in the use of ‘together’ for ‘thegither’ in order to allow a rhyme with ‘heather’. In general standardised sub-poetic English is used to provide the rhythm and rhyme as in ‘shore’ and ‘adore’. Scots words are scattered within an English structure to give a flavour of Scottishness.

The tone of the monologue you read in Activity 7 is sentimental recall of a distant place, which only becomes close through emotion. The question remains, in what way the satiric humour, previously a key element of storytelling in Scots, is still playing a part in Frame’s monologue.

The lines following what you have read above, recover a sense of spoken Scots idiom, but only to exhibit it as quaint and couthy. This can be seen in the rhymes, which are still dominated and dictated by English, as well as in the repetitions, which give the monologue the character of a children’s poem or song.

But stop a wee, wheest, haud yer tongue.

Noo whether auld or whether young,

We like a laugh, we like a joke,

We like a sang, like a’ Scotch folk:

We like a crack- an oor or twa-

Aboot the days that’s long awa’…

We’ll just imagine we’re at home-

Back tae dear auld place again;

Back ta ethe toon, back tae the fairm;

Back tae the guid auld harum scarum.

But, hoots, I think I’ve said enough,

My very tongue is getting touigh.

So if you please, jist touch thae keys,

An’ at my ease, tae tell nae lees,

I’ll sing a song, and tell a wheeze.

This is carefully crafted to appeal to an emigrant audience, but the attitudes and emotions expressed soon became indicative of ‘Scottishness’ in a period when despite its industrial success Scotland had no distinctive political or cultural status.

Other famous names were to follow Frame, including the music hall artist from Dundee, Will Fyffe, the gifted comic who wrote ‘I Belong to Glasgow’ [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] , and pre-eminently Harry Lauder, the Edinburgh-born singer and comedian who achieved international success.

Activity 8

In this activity you will work with one of Lauder’s most famous songs, ‘Wee Deoch an Doris’. The phrase ‘deoch an doris’ is Gaelic and means a parting drink offered to guests, ‘one for the road’. It is interesting how Lauder mixes Gaelic and Scots in the heading by adding the adjective wee to the Gaelic phrase, all in an effort to create a sense of ‘Scottishness’.

Listen to the song performed by Harry Lauder.

While listening, read the lyrics below. When reading and listening to the lyrics of this song, pay particular attention to when and how Scots language is used here.

You may also want to compare Lauder’s use of the Scots language with how Frame used Scots in his monologue.

There's a good old Scottish custom that has stood the test o' time,

It's a custom that's been carried out in every land and clime.

When brother Scots are gathered, it's aye the usual thing,

Just before we say good night, we fill our cups and sing..

Chorus

Just a wee deoch an doris, just a wee drop, that's all.

Just a wee deoch an doris afore ye gang awa.

There's a wee wifie waitin' in a wee but an ben.

If you can say, "It's a braw bricht moonlicht nicht",

Then yer a'richt, ye ken.

Now I like a man that is a man; a man that's straight and fair.

The kind of man that will and can, in all things do his share.

Och, I like a man a jolly man, the kind of man, you know,

The chap that slaps your back and says, "Jock, just before ye go..."

Chorus

I'll invite ye a' some other nicht, to come and bring yer wives.

And I'll guarantee ye'll have the grandest nicht in all yer lives.

I'll have the bagpipes skirling

We'll make the rafters ring.

And when yer tired and sleepy, why I'll wake yer up an' sing:

Answer

This is a model answer. Your answer might be different.

The process begun by Frame goes further here with the dominance of English ‘in a Scottish accent’. What is even more interesting though is the use of Scots and a kind of ‘pidgin Gaelic’ in the chorus. Everything is ‘wee’, and Scots has become something you say or sing when drunk. This is not so much using Scots, as exhibiting it as a linguistic marker of cultural stereotypes.

Of course, Lauder is well aware they are stereotypes and deploys them for comic effect, for example in the line: The chap who slaps your back and says “Jock, before you go”. But the humour is superficial, a back-slapping endorsement of something that lacks social reality or emotional truth.

13.2 Humorous folk tales in Scots