14.2 Historical events with an impact on Scots

In this part, you will learn about some key events which affected the use, status and development of Scots.

In 1513, the Scots suffered a disastrous defeat at the hands of an English army at the Battle of Flodden, which saw the death of King James IV and many of the Scottish nobility. A long period of instability followed during the minority rule of James V, the patronage of poets at the royal court was not sustained, and the richest period of literary writing in Scots came to an end.

In 1542, James V died and was succeeded by his infant daughter Mary. In the first months of her reign, in March 1543, an Act of Parliament was passed authorising the use of a vernacular Bible (that is, one not in Latin).

Listen to the Act read by Jeremy Smith.

Transcript

It is statute and ordanit that it salbe lefull to all oure sovirane ladyis lieges to haif the haly write, baith the New Testament and the Auld, in the vulgar toung, in Inglis or Scottis, of ane gude and trew translatioune and that thai sall incur na crimes for the hefing or reding of the samin.

It is interesting that no preference was made between ‘Inglis’ and ‘Scottis’ as to which ‘vulgar toung’ should be used. This Act predates by eighteen years the Reformation of 1560 led by John Knox. It was largely because of the close links between Knox and other Reformers and England, and the ready availability of copies printed in English, that by the end of the century it had become normal to read and hear from the Bible in that language, not in Scots. Some partial Scots translations were made but they were not published.

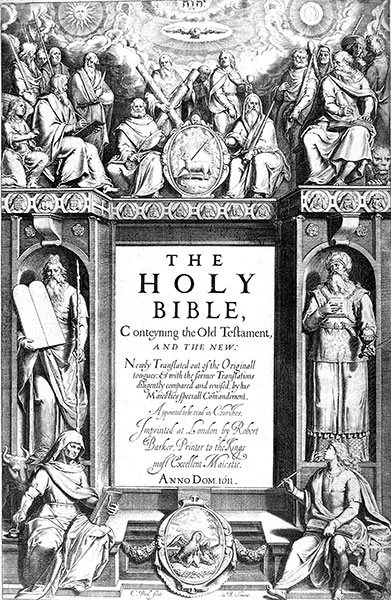

With the Union of the Crowns in 1603, James VI left Scotland and ruled his kingdoms from London. In 1611, a new translation of the Bible, authorised by James, was published. We know this as the Authorised Version or King James Bible, and it became universally used throughout the British Isles. Historically, this Bible has had more influence on the cultural life of Scotland than any other book.

The fact that it was written in English was a major factor in strengthening the position of English as the language of formal writing and discourse in all walks of life, not just religion. Arguably, it also helped to create a perceived ‘superior’ status of English over Scots.

Activity 5

James VI was himself a poet and gathered a group of other poets around him at his court in Edinburgh, known as the Castalian Band. An important effect of the removal of the court to London was that royal patronage of the arts, and literature in particular, was abruptly curtailed in Scotland. Even before James’s departure, however, it is possible to see a shift in language priorities happening in Scotland.

Compare the following two extracts from James’s prose work on statecraft, Basilicon Doron (Greek for ‘royal gift’). The first extract comes from the manuscript of the book, written in Scots in 1598, and the second from the edition published in 1603 by Robert Waldegrave, the King’s official printer, in Edinburgh.

The closer political and economic ties between Scotland and England, especially after the Union of Parliaments of 1707, meant that the language of the larger, stronger nation became the standard, official language of both.

But it is important to note that this divergence between ‘formal’ and written English and ‘informal’ and spoken Scots was already happening before the Union: the close relationship between the languages undoubtedly facilitated this process, as many Scots speakers were well able to read, write and speak English when they needed to do so.

During the 18th century scientific and philosophical movement we now call the Scottish Enlightenment, it suited writers such as David Hume and Adam Smith to write their books in English, and to learn how to eradicate what were called ‘Scotticisms’ from their prose, even though they continued to speak Scots in their daily lives. The market for their ideas was clearly much greater if they wrote in English.

Yet, this same period was precisely when the ‘Vernacular Revival’ [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] of poetry and song composed in Scots, mentioned in section 2 of this unit, was taking place. This suggests that the intellectual and commercial attractions of English were balanced by an equally strong need to express some feelings.

14.1 The status and use of Scots from c.1100 to the present