15.1 Scots language variations in 16th century Bible translations

In the 16th century, Roman Catholic and Protestant reform movements emphasised the need for more understanding, and more personal styles of devotion. Literacy was spreading especially in the towns and the greater availability of books encouraged more reading and more translation of texts. Scholars studied the Christian Bible in Greek and Hebrew, stimulating new interpretations.

Above all, Protestant reformers such as Martin Luther and William Tyndall translated the Bible into commonly spoken or vernacular languages such as German and English. Their aim was to challenge the authority of the Roman Catholic Church and its interpretation of Christianity’s sacred texts.

In the 16th century, the most commonly spoken languages in Scotland were Scots and Gaelic. Scots was dominant in urban areas and was the language chosen when the Roman Catholic authorities tried to encourage a greater knowledge of religious teaching across the population. The example sentence in the handsel was one of seventy texts or sayings that the influential John Hamilton, archbishop of St Andrews wanted people to memorise, through his Hamilton’s Catechism [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] printed in St Andrews in 1551:

AS THE GUID BUIK SAYS, LUVE GOD ABUVE AL AN YI NYCHTBOUR AS YERSEL.

This is, in Scots, what Christ says in the New Testament when he is asked what is the most important thing in the Jewish Law or Torah. His words, in the familiar English of the Authorised Version are, ‘You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and soul and strength, and your neighbour as yourself’. The Scots version above is compressed, pithy and to the point.

Activity 4

In this activity, you compare three different translations of Christ’s words cited above. Note your comments on the literal vs the literary translation and why you think the notable differences arise.

a. [Scots of 1555]

As the Guid Buik says, luve God abuve al an yi nychtbour as yersel

b. [English Authorised version]

You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and soul and strength, and your neighbour as yourself.

c. [Word-for-word translation of Scots in English]

As the good book says, love God above all and your neighbour as yourself.

* Note in the word-for-word version it is “the good book” instead of “The Bible” as used in the example sentence above as well as the handsel.

Answer

This is a model answer, your notes might be different.

As the text says, the Scots version is compressed and yes, it is quite to the point. There is an element of poetry to the English Authorised Version – but yes, it does use quite a few more words to say the same thing. Having said that, the word-for-word Scots translation does seem to lack emphasis which the English contains when going into detail such as “all your heart and soul and strength” instead of just “abuve al” like in the Scots version from 1555.

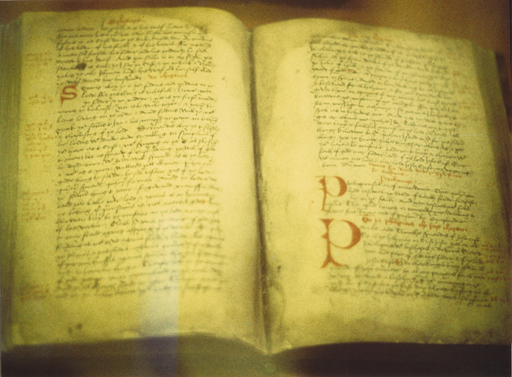

Scottish Protestants were keen to see the whole of the Christian Bible available in Scots. A radical Ayrshire reformer, Murdoch Nisbet worked in secret to translate the New and parts of the Old Testament, working from the Latin Vulgate and an English ‘underground’ version originally created by the Lollards, the 14th century dissenters, inspired by John Wycliffe.

Murdoch Nisbet’s translation of the New Testament into Scots was the first ever undertaken. [… His] New Testament is a wonderful source of information on what the differences between English and Scots at that period were thought to be. A striking feature of the Scots translation is that to the modern eye it is actually rather more accessible than the English.

Nisbet hid his work in a cellar beneath his house where he also held illegal religious gatherings, or conventicles, at which he read aloud from his translation. His labour continued for decades – beginning perhaps in Europe – until his death in 1559. However, Nisbet’s New Testament received no official recognition and was only published as a historical source text in 1901–05.

Why did this happen? The Protestant Reformers wanted to transfer the focus of religious inspiration and authority from the Church to the Bible. The written and printed Buik was to become the mainstay and guide. But the newly translated Bible came from Geneva, where John Calvin had established a Reformed city state, and where John Knox lived in exile between 1556 and 1559. More specifically, Knox was a minister in Geneva to the English-speaking congregation which was composed of prominent Protestants who had fled the rule of the Roman Catholic Mary Tudor in England.

The learned among them set about creating the Geneva Bible, an updated version of William Tyndale’s English translation published in 1526, and Knox provided the explanatory or interpretative notes for this definitive Protestant version. When Knox returned to Scotland in 1559, he brought with him the Bible and the Protestant orders of service, which had become established in Geneva. These then became the Scottish norm.

Here is the passage in Murdoch Nisbet’s Scots translation that parallels Archbishop Hamilton’s Catechism, containing the text inscribed on John Knox House:

And ane of them, a techer of the law, askit Jesu, tempand him, Maistre, whilk is a gret comendment in the law? Jesus said to him, Thou sal lufe thi Lord God of al thi hart, and in al this saule, and in al thi mynde. This is the first and the gretest commandment. And the second is like to this, Thou sal luf thi nechbour as thir self.

You can now listen to this passage being read out to further develop your understanding of older spoken Scots.

Transcript

And ane of them, a techer of the law, askit Jesu, tempand him, Maistre, whilk is a gret comendment in the law? Jesus said to him, Thou sal lufe thi Lord God of al thi hart, and in al this saule, and in al thi mynde. This is the first and the gretest commandment. And the second is like to this, Thou sal luf thi nechbour as thir self.

This passage from Nisbet’s text is an example of the fact that Scots was used in both written and spoken forms in the 16th century, and had commonly applied standards, despite variations in spelling – just like the situation we have today.

There is a further famous passage in Murdoch Nisbet’s Scots translation, that describes what came to be known as the ‘Last Supper’, a final meal shared between Jesus and his disciples. This event became the basis of the most important Christian service and liturgy, in both Roman Catholic and Protestant traditions.

Activity 5

In this activity you will compare the passages about the ‘Last Supper’ from Nisbet’s version in Scots with that of the Bassendyne Bible of 1579, the first non-Latin Bible to be printed in Scotland, which was a direct reprint of the second edition of the Geneva Bible published first in 1560.

Listen to both passages first of all and take some notes to answer the following questions.

- What are the differences and commonalities in the two passages?

- Did you find it difficult to follow the spoken Scots?

- Which passage is more ‘to the point’?

a. The ‘Last Supper’ passage from Nisbet’s version

Transcript

And quhen they soupet, Jesus tuke brede and blessit and brak, and gafe to his disciplis, an said, Tak ye, and ete ye. This is my body. And he tuke the cup, and did thankingis, and gafe to thame and said, Drink ye all hereof. This is my bluide of the new testament, quilk salbe sched for mony into remissioun of sinnis. And I say to you, I sal nocht drink fra this thyme of this kynde of wyne, til into that day quhen I drink it anew with you in the kingdom of my fader.

b. The same passage in the Bassendyne or Geneva Bible

Transcript

And as they did eat, Jesus toke the bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it, and gave it to the disciples, and said, Take eat, this is my bodie. Also he toke the cup and when he had given thanks, he gave it to them, saying, Drinke ye all of it. For this is my blood of the Newe Testament, that is shed for mannie for the remission of sinnes. I say unto you that I will not drinke hence forthe of this fruit of the vine until that day, when I shal drinke it newe with you in my Father’s kingdome.

Answer

This is a model answer. Your notes might be different.

Remembering that behind both passages is a common source text, it is still interesting to see how the two versions are mutually comprehensible, and yet significantly different. The main differences are due to the character of spoken Scots in that period – ‘and quhen they soupet’.

The Genevan English is slightly more formal, and of course more familiar as it is clearly the forerunner of the later English Bible, which was formally established in the Authorised Version published in 1611, commissioned by James VI of Scotland and I of England. However, Nisbet’s version is more to the point, more personal and ‘down to earth’, directly relating to the general public and the way these people used Scots at the time.

As discussed above, the Bible or sacred text – the BUIK – sits alongside the liturgies or services of worship. The Genevan Church also produced a book of liturgies giving instructions and further texts applicable to most religious occasions, while excluding festivals such as Easter and Christmas, which they believed had no precedent in the Bible.

John Knox and his Scottish colleagues endorsed this Book of Common Order and had it published in Edinburgh, again in an English version which had been developed by Knox’s English speaking congregation in Geneva. The Book of Common Order was also translated into Gaelic on the instruction of Bishop John Carswell of Argyll, becoming the first printed book in Scottish Gaelic. But the Scots language received no recognition or expression in these official texts of the Scottish Protestant Reformation.

The Book of Common Order, as published in Scotland in 1562, cites the passage from the Apostle Paul in the New Testament on which the Protestants based their version of Holy Communion – the Lord’s Supper. This is clearly related to the passage quoted in Activity 5 in Matthew’s Gospel, and may derive ultimately from a shared oral tradition.

The Lorde Jesus, the same night he was betrayed, toke bread, and when he had geven thankes, he brake it, saying, Take ye, eate ye, this is my bodie which is broken for you; doo this ion remembrance of me. Likewise after supper he toke the cuppe, saying, This cuppe is the newe Testament or covenant in my bloude, doo ye this so ofte as ye shall drinke therof, in remembrance of me. For so ofte as ye shall eate this bread and drinke of this cuppe, ye shall declare the Lordes death until his comminge.

Here is a recording of this passage to help you get a feel for the rhythm and sound of this version in Medieval English.

Transcript

The Lorde Jesus, the same night he was betrayed, toke bread, and when he had geven thankes, he brake it, saying, Take ye, eate ye, this is my bodie which is broken for you; doo this ion remembrance of me. Likewise after supper he toke the cuppe, saying, This cuppe is the newe Testament or covenant in my bloude, doo ye this so ofte as ye shall drinke therof, in remembrance of me. For so ofte as ye shall eate this bread and drinke of this cuppe, ye shall declare the Lordes death until his comminge.

The influence of this written text of 1562 persists to this day in the services of the Protestant Church of Scotland, and the Free Presbyterian Churches, exposing the widely shared misconception that the Presbyterians had no set prayers or liturgies. Equally, that continuity demonstrates the influence of the liturgy in excluding Scots as an official language for religious purposes.

Activity 6

Now compare the passage from The Book of Common Order in English – as seen above – with Nisbet’s version of the same passage in Scots.

Part 1

Listen to the same passage from Nisbet’s version in Scots. You may also want to record yourself reading this out and then compare your version with our model.

Transcript

Listen

For the Lord Jesu, in qhat nycht he was betrayit, tuke brede, and did thankingis, and brak, and said, Tak ye, and ete ye; This is my bodie, quilk shalbe betrait for you; do this thynge into my mynde. Alsa the cup, eftere that he had soupit, and said, This cuip is the newe testament in my blude; do ye this thing, als aft as ye sal drink, into my mynde. For als afty as ye sal ete this brede and sal drink the chalice, ye sall tell out the dede of the Lord, till that he cum.

Model

For the Lord Jesu, in qhat nycht he was betrayit, tuke brede, and did thankingis, and brak, and said, Tak ye, and ete ye; This is my bodie, quilk shalbe betrait for you; do this thynge into my mynde. Alsa the cup, eftere that he had soupit, and said, This cuip is the newe testament in my blude; do ye this thing, als aft as ye sal drink, into my mynde. For als afty as ye sal ete this brede and sal drink the chalice, ye sall tell out the dede of the Lord, till that he cum.

Activity 7

This second section of unit 15 mentions a number of people who were influential in religious reforms and translations of the Bible in the 16th century. In this activity, you will be able to remind yourself of the most prominent 16th century reformers and their contribution.

The names of the reformers are listed in the order in which they appear in this section.

- a.Without reading the section again, match the names with their achievements.

- b.Once you have completed the matching exercise, you might want to revisit section 2 and take a note of any other important aspects relating to the reformers mentioned here.

Two lists follow, match one item from the first with one item from the second. Each item can only be matched once. There are 7 items in each list.

-

Martin Luther

-

William Tyndall

-

John Hamilton

-

Murdoch Nisbet

-

John Knox

-

James VI of Scotland

-

John Carswell

Match each of the previous list items with an item from the following list:

a.Roman Catholic, wrote an influential Catechism in Scots

b.Protestant Reformer, secretly translated Bible into Scots

c.Protestant Reformer, made an English Bible translation the norm in Scotland

d.Protestant Reformer, translated The Book of Common Order into Scottish Gaelic

e.Protestant Reformer, translated Bible into vernacular language

f.Protestant, commissioned Authorised English Version of the Bible

g.Protestant Reformer, translated Bible into vernacular language

- 1 = e,

- 2 = g,

- 3 = a,

- 4 = b,

- 5 = c,

- 6 = f,

- 7 = d

15. Introductory handsel