19.1 Examples of prose fiction written in Scots

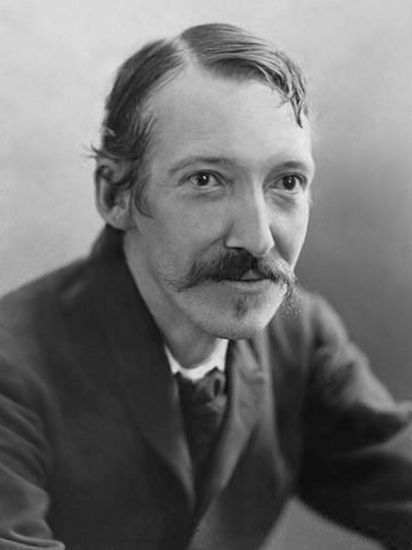

This section will focus on two stories, Walter Scott’s Wandering Willie’s Tale and Robert Louis Stevenson’s Thrawn Janet. The section will consider the ways in which Scots language is used in relation to English in the stories, how the stories themselves balance aspects of the supernatural and the material or earthly world. They will explore questions of who the narrator is and who the narrative is addressed to, and finally what legacy the stories imply for their own narrators and for subsequent readers. This last question prompts consideration of the relation between storytelling and extended prose fiction, novels.

The Scots language in these two stories is used to particular effect, not only to generate a quality of strangeness or mystery but also to give a sense of vocal immediacy or authenticity. This is a paradox: one aspect of its use as written, printed language exploits its unfamiliarity: to those accustomed to seeing the English language on the page, then Scots may seem odd or difficult; the other aspect exploits the colloquial intimacy of Scots language and implies that the speakers of these stories are talking ‘naturally’.

We know that all literature is artifice – all the arts employ design or intention, structure and method – but the relation between writing and speech is a palpable presence in these stories. How does this work? What effect does it have? You will answer these questions through exploring the two stories in some detail.

Activity 4

One of the most helpful essays on the art of storytelling and its distinction from the art of the novel is The Storyteller: Reflections on the Works of Nikolai Leskov (1936) by Walter Benjamin. You will read parts of this short essay in this activity, as it will form one of the cornerstones of this unit.

Read Benjamin’s essay [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] , focusing mainly on sections I–V, and then match the beginnings of the sentences with the appropriate ending according to Benjamin’s text.

We have done the first example for you:

Mankind is losing… /… the ability to exchange experiences.

Two lists follow, match one item from the first with one item from the second. Each item can only be matched once. There are 7 items in each list.

…differs least from the speech of the many nameless storytellers.

…with the lore of the past, as it best reveals itself to natives of a place.

…contains, openly or covertly, something useful.

…is a symptom of the decline of storytelling.

…is its essential dependence on the printed book.

…and in turn makes it the experience of those who are listening to his tale.

…who is no longer able to express himself by giving examples of his most important concerns as he has not experienced these himself or heard from others who did.

Match each of the previous list items with an item from the following list:

a.The rise of the novel at the beginning of modern times…

b.The most effective stories combine the lore of faraway places, such as a much-traveled man brings home…

c.What distinguishes the novel from the story…

d.The novelist has isolated himself, a solitary individual…

e.The storyteller, a social being, takes what he tells from experience - his own or that reported by others...

f.The nature of every real story...

g.The great storytellers are those whose written version…

- 1 = g,

- 2 = b,

- 3 = f,

- 4 = a,

- 5 = c,

- 6 = e,

- 7 = d

Benjamin draws our attention to a number of things, which can illuminate our reading of Scott and Stevenson and how their Scots language stories work in these examples. I’d like to draw attention to two key comparisons he makes. One is between the storyteller who stays at home and knows all about a particular locality, its inhabitants and ways of life; the other is the storyteller who travels the world and visits other places, returning with news of foreign parts and different customs. What categories do the narrators of the Scott and Stevenson stories most closely fit? The second thing is the difference between the storyteller and the novelist.

In the oral tradition, the storyteller is always present, telling the story; in the printed tradition, the novelist is almost always absent (except, these days, at book festivals and signings). You will now investigate how this observation applies to the narrators in Scott’s and Stevenson’s stories.

Let’s start with the older text, Scott’s ‘Wandering Willie’s Tale’ from 1824, which forms chapter six of the novel Redgauntlet. It is worth thinking about the novel and the story’s place within it before looking at the story itself:

Scott's silence [towards publisher and friends] as to the novel he was actually composing -- a silence which verges on deliberate misdirection -- lends support to the widely held view that Redgauntlet is Scott's most deeply personal novel. It offers more parallels with Scott's own life story than any other Waverley Novel. In particular, it draws on Scott's training as a lawyer and preparation for the bar […], on the tour of the Lake District in 1797 when he met his wife […], and on a professional visit to Dumfries and Galloway in 1807. Many commentators have detected a self-portrait in the young lawyer Alan Fairford, and a depiction of Scott's own father in the sternly Presbyterian Saunders Fairford. Models for Alan's friend Darsie Latimer have been sought in Scott's fellow students William Clerk and Charles Kerr of Abbotrule.

The narrator of the story is a character in the novel. The Scots of his story is embedded within the English of the narrative as a whole. Earlier chapters of the novel take the form of letters between characters, mainly in English, and the overall narrative of the book – Scott’s voice, one might argue – is given in English. So while the authority of Wandering Willie’s Scots is undisputed while the story lasts, it passes away into the larger context. But this can be regarded as something of a paradox. The story has been anthologised and read, probably, by more people over centuries, than have read the novel as a whole. That Scots voice and language has a lasting hold on the imagination of readers in a way that the novel only partly offsets. It has its own authority despite its context.

Activity 5

Part 2

In the closing dialogue at the end of the story (the end of the novel’s chapter six), Willie tells his companion that “it is nae chancy thing to tak’a stranger traveller for a guide when you are in an uncouth land.” His companion, who is the main link to the novel’s main narrative, responds by saying that he should not have thought so, since the narrator’s grandfather’s adventure as recounted in the tale “was fortunate for himself, whom it saved from ruin and distress; and fortunate for his landlord.” And then Willie delivers the final revelation, the moral of the tale, which taints the ending of the story and suggests a world of unpredicted consequences. And this is the element Benjamin labelled the ‘nature of every real story […] something useful’ – a lesson to be learned.

Listen to the moral of Willie’s tale and read it out yourself. What do you think is the lesson of the tale?

Transcript

Listen

Aye, but they had baith to sup the sauce o’ ‘t sooner or later,’ said Wandering Willie; ‘what was fristed wasna forgiven. Sir John died before he was much over threescore; and it was just like of a moment’s illness. And for my gudesire, though he departed in fullness of life, yet there was my father, a yauld man of forty-five, fell down betwixt the stilts of his plow, and rase never again, and left nae bairn but me, a puir, sightless, fatherless, motherless creature, could neither work nor want. Things gaed weel aneugh at first; for Sir Regwald Redgauntlet, the only son of Sir John and the oye of auld Sir Robert, and, wae ’s me! The last of the honorable house, took the farm aff our hands, and brought me into his household to have care of me. My head never settled since I lost him; and if I say another word about it, deil a bar will I have the heart to play the night. Look out, my gentle chap,’ he resumed, in a different tone; ‘ye should see the lights at Brokenburn Glen by this time.

Model

Aye, but they had baith to sup the sauce o’ ‘t sooner or later,’ said Wandering Willie; ‘what was fristed wasna forgiven. Sir John died before he was much over threescore; and it was just like of a moment’s illness. And for my gudesire, though he departed in fullness of life, yet there was my father, a yauld man of forty-five, fell down betwixt the stilts of his plow, and rase never again, and left nae bairn but me, a puir, sightless, fatherless, motherless creature, could neither work nor want. Things gaed weel aneugh at first; for Sir Regwald Redgauntlet, the only son of Sir John and the oye of auld Sir Robert, and, wae ’s me! The last of the honorable house, took the farm aff our hands, and brought me into his household to have care of me. My head never settled since I lost him; and if I say another word about it, deil a bar will I have the heart to play the night. Look out, my gentle chap,’ he resumed, in a different tone; ‘ye should see the lights at Brokenburn Glen by this time.

Unlike Willie’s story, Stevenson’s Thrawn Janet (1881) was written as a complete work in itself, and published as soon as it was sent to the Cornhill Magazine after its completion. Stevenson begins the story in relatively straightforward English but moves into Scots very quickly and stays there. The Scots-speaking storyteller carries you through the tale and no return to an authoritative English language narrative comes at the end.

Activity 6

In this activity, you will establish to what effect and with what purpose the Scots language was used by Stevenson in this story.

Listen to the story read by the novelist, poet, playwright and performer Alan Bissett; or you can read the text of ‘Thrawn Janet’.

While reading/listening to the story, think about in what way Benjamin’s distinction between storyteller and novelist applies here. And what effect does the use of the Scots language have in terms of the authority of the narrator?

Answer

This is a model answer. Your notes might be different.

Walter Benjamin’s observation that one difference between (oral) stories and (printed) novels is that the storyteller is there in front of you all the time, while the novelist is hardly ever present. Here, Stevenson is playing on that truth: the storyteller in Thrawn Janet retains the narrative voice until the end, even though Stevenson, the author, has written and seen to that voice appearing in print for a wide readership. He’s playing with expectations that an omniscient narrator will return to vouchsafe good authority, and given that the subject of the narrative is what befalls a minister of the church, the implication is pretty clear that no such “grand narrator” is there at all.

All you have is the evidence of your eyes and experience to go on. Stevenson was writing at the other end of the 19th century from Scott. Darwin and Marx had made their intervention and Nietzsche and Freud were about to make theirs. Stevenson is more subtle than any of them but the implications of his work are as deep, and it’s through his use of Scots in this story that he presents them.

19. Introductory handsel