19.3 The predicament of the Scottish writer

Activity 8

In this section, you are going to consider the aspects listed in the questions below. While studying this section, take notes on these questions.

- What are the major points made by Edwin Muir in Scott and Scotland? Are they defensible?

- How did Hugh MacDiarmid respond to this in The Golden Treasury of Scottish Poetry (1940)?

In the late 1930s, a series of books with the generic title The Voice of Scotland was initiated by Grassic Gibbon and Hugh MacDiarmid. Their intention was to invite a range of contemporary authors to write book-length essays on contentious themes and questions of the day.

Thus, Compton Mackenzie wrote Catholicism and Scotland, reminding predominantly Protestant readers that their greatest Scottish heroes, Wallace and Bruce, were pre-Reformation Catholics. Neil Gunn wrote Whisky and Scotland rehearsing all the ceremonies, rituals and traditions whisky-drinking once entailed, intrinsically celebrating sensitivity and care alongside carefully applied intoxication and language at play. Victor McClure wrote Scotland’s Inner Man about what good food and a healthy diet actually was and might again be in Scotland. Eric Linklater wrote The Lion and the Unicorn: what England has meant to Scotland and William Power wrote Literature and Oatmeal.

In the last in the series, Scott and Scotland: The Predicament of the Scottish Writer, Edwin Muir concluded that the only way to take Scottish literature forward was to write exclusively in English. Gaelic would not serve and Scots was inadequate: only English could address an international readership, as was evident in the literary triumphs of W.B. Yeats and James Joyce.

Not only MacDiarmid, whose Scots-language poetry had been so revolutionary in the 1920s, but also the composer F.G. Scott, were furious. Scott’s brilliant settings of MacDiarmid, Burns, William Soutar, George Campbell Hay and others, encapsulated a Scots musical idiom in compositions self-consciously drawing on modernist innovations from Schoenberg, Satie and Stravinsky, while keeping the traditional sense of Scots song in play. Scott met Edwin Muir and his wife Willa and wrote of their meeting, “I had a long and very exciting talk with the pair of them, told them that I disagreed with everything in the book.” He argued definitively that there were poems in Scots (not least those of Burns) that were by any standards ‘major’. Edwin, Scott reported, could not contradict him. Willa “turned extremely grave and silent”.

In the long run, Muir had a point: Yeats and Joyce have an international cachet still not fully extended to MacDiarmid, Soutar or Grassic Gibbon, and there are still many folk unwilling to recognise Scots as a language no less valid than English. Yet MacDiarmid and F.G. Scott won the argument. One response to this argument was MacDiarmid’s editing of an anthology entitled The Golden Treasury of Scottish Poetry [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] , which for the first time emphasised Gaelic and Latin language traditions as well as those of Scots and English, in Scottish literature.

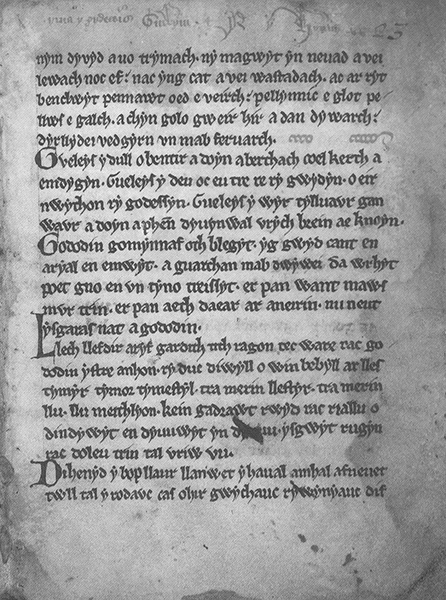

There is also important poetry in French (by Mary Queen of Scots, for example) and the first poem we might identify as Scottish, The Gododdin, was written in what we call Old Welsh or Cymric. In the 21st century, the understanding that multilingualism, a plurality of languages, is characteristic of Scottish literature in a way that distinguishes it from the more familiar ‘one nation, one language’ imperial ideal, is generally acknowledged, and open. The linguistic diversity of contemporary Scottish writing is proof, and one might consider examples from James Kelman’s Booker-prizewinning novel How Late It was, How Late (1994) and Irvine Welsh’s Trainspotting (1996).

In this context, it is beneficial to recall how inflammatory the questions raised here may be. In the New York Times (29 November 1994), Sarah Lyall reported:

No sooner had James Kelman's novel How Late It Was, How Late won this year's Booker Prize for fiction than a full-scale furor erupted. One of the judges, Rabbi Julia Neuberger, declared that the book was unreadably bad and said that the awarding of the prize, Britain's most important, was a “disgrace.” Simon Jenkins, a conservative columnist for The Times of London, called the award “literary vandalism.” Several other critics sniped that the book should have been disqualified because of its heavy use of profanity.

Meanwhile, the British literary establishment huddled together defensively as Mr. Kelman appeared in a business suit at the black-tie Booker affair and, in his heavy Scottish accent, made a rousing case for the culture and language of “indigenous” people outside of London. “A fine line can exist between elitism and racism,” he said. “On matters concerning language and culture, the distinction can sometimes cease to exist altogether.”

This recalls Mark Twain’s ‘Explanatory’ note at the beginning of Huckleberry Finn (1884):

In this book a number of dialects are used, to wit: the Missouri negro dialect; the extremest form of the backwoods Southwestern dialect; the ordinary ‘Pike County’ dialect; and four modified varieties of this last. The shadings have not been done in a haphazard fashion, or by guesswork; but painstakingly, and with the trustworthy guidance and support of personal familiarity with these several forms of speech. I make this explanation for the reason that without it many readers would suppose that all these characters were trying to talk alike and not succeeding.

Twain’s ironic and bitter humour comes through especially in that last sentence. By emphasising the subtle and not-so-subtle differences in dialect and language forms and idioms, by drawing attention to their representation in his novel, Twain is also indicating a quality inherent in racist superiorism, the tendency to be disdainful of such matters from a position of power and contempt. That relationship of power, and the relationship between speech and writing, is at the heart of our enquiry into the Scots language in literary prose.

19.2 Lewis Grassic Gibbon and A Scots Quair