19.4 Literary prose fiction in Scots from 1900 to new millenium

In this this section, you are going to focus on the authority of the Scots language in prose fiction from the 19th until the 20th century. The important thing is to understand not only the arguments but to consider them in their historical context. For example: Scots was a language of formal occasion, political authority and serious social functions, yet it was always related to speech and could modulate tone, balancing irony and directness in particular ways. At different periods in history, Scots in literary prose was in contest with the authority of the English language but the contest has been resolved over the period of around 1936 to 1999 (How Late It Was).There is a distinctive tension between the use of the voice in Scots prose and its local provenance, and the use of ‘neutrality’ or ‘objectivity’, which purports to deliver an omniscient authority.

One of the most important books to present the hinterland of writing Scots prose fiction is William Donaldson’s Popular Literature in Victorian Scotland (1986). Donaldson draws attention to ‘a new professional type’ of writer such as William Alexander, who write for the popular local press, in his case in Aberdeenshire, extended prose fiction in a local dialect form of Scots.

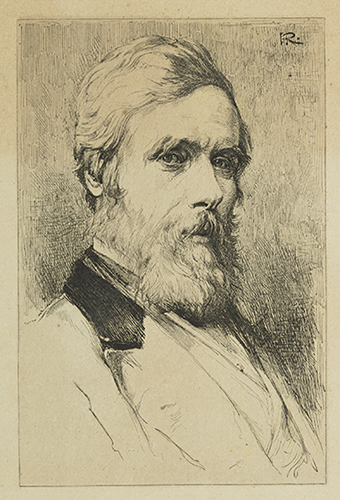

William Alexander, who was one of the leading journalists in Victorian Scotland and

…politically, he was a radical, supporting land reform and the abolition of hereditary privileges. Alexander was a prolific novelist of wide thematic range and considerable variety of style, from austere realism at one end of the scale, to mellow social comedy at the other. His works were serialised in popular newspapers. He consciously avoided the book as a publication vehicle.

His work was published in the periodical press and collected in complete novels such as Johnny Gibb o Gushetneuk (1877).

Activity 9

In this activity you will work with an extract from the second chapter of Alexander’s Johnny Gibb o Gushetneuk.

Read the extract and analyse it closely for the way it slips between Standard English and Scots forms. Highlight the Scots language in the extract as you read. Then think about the purpose and effect of the slipping between the two languages.

Discussion

Note:

The use of Scots in this passage adds, as we have seen in many other examples in this unit, an element of authenticity and realism through by naming key elements of the custom using Scots terms. There is a clear distinction made between the Scots and the English in most cases, where the Scots words are even visibly separated from the English. The tone of speech idiom is consistently conversational but the way in which Scots is introduced – often in quotation marks – indicates its particular and different provenance. Alexander’s prose uses Scots confidently and with a sense of local authority yet it still maintains an apparently formal ‘objectivity’ in its deployment of English and the relation this sets up between English and Scots.

Compare this with MacDiarmid’s revitalisation of Scots in the 1920s partly for his own individual creative priorities, partly to counter the increasingly familiar use of Scots in popular media, music hall and film, especially widespread in the establishment propaganda. MacDiarmid, in his short story or prose sketch ‘The Waterside’, uses Scots throughout and slips quickly and with great fluency between thoughtful, more meditative reflections, and representations of fast, dramatic action. These are sometimes serious – the threat to the children on the broken bridge is real – but also, at the same time, sometimes wildly comic. The moment where a mother rescues one child then finding it is not hers, throws it back into the water, is both ferociously comic and terribly chilling, partly because it seems to represent natural and understandable human behaviour, even if that behaviour is in some respects reprehensible.

The use of Scots in his prose and discussed in his essays ‘A Theory of Scots Letters’ and ‘English Ascendancy in British Literature’ shows a development and resistance to what MacDiarmid calls ‘English Ascendancy’: in other words, the way in which, over time, English has come to seem the normative language in Britain, while other languages are neglected or suppressed. Seamus Heaney, when discussing MacDiarmid’s literary use of Scots, established:

“…a demonstrable link between MacDiarmid’s act of cultural resistance in the 1920s and the literary self-possession of writers such as Alasdair Gray, Tom Leonard, Liz Lochhead and James Kelman in the 1980s and 1990s. [For Heaney, MacDiarmid’s poetry] prepared the ground for a Scottish literature that would be self-critical and experimental in relation to its own inherited forms and idioms, but one that would also be stimulated by developments elsewhere in world literature”.

And we conclude with a statement by Margery Palmer McCulloch, who verifies that Heaney’s comment, quoted above, represents “a meaningful endorsement of the way in which the inter-war Scottish Renaissance attempt to change the direction of Scottish literary (and ultimately political) culture, with its strong emphasis on national identity as well as international relationships and influences, [which] has been able to modify itself over the decades to bring about the confident, diverse yet recognisably Scottish contribution to international writing we have today” (2012, p. 73).

19.3 The predicament of the Scottish writer