Background (spirometry and lung function)

Background

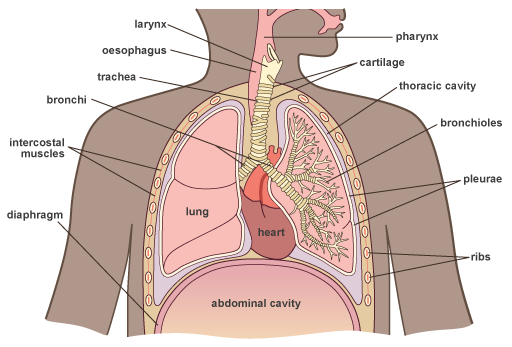

In this lesson you will use an online Spirometer to investigate the changes in the amount of air moved into and out of the lungs. Movement of air in and out of the lungs is called pulmonary ventilation and it involves the main structures of the respiratory system (Figure 1):

Figure 1. (a) Cross-section through the structures of the respiratory system.

When we breathe in, oxygen rich air enters the body through the nostrils and passes into the nasal cavities.

From the nasal cavities, the air passes to the pharynx (throat) at the back of the mouth where it is joined by air that has entered the system through the mouth.

Air passes into the trachea which is held open by rings of cartilage, and then enters the bronchi and bronchioles.

The trachea then divides into two branches called bronchi (singular: bronchus) (Figure 1). These serve the left and right lungs. Like the trachea, the walls of the bronchi contain cartilage, which prevents their collapse. Each main bronchus divides into smaller and smaller tubes, finally ending in terminal bronchioles. Bronchioles also contain cilia that help to keep the airways clean by moving mucus and particles from the lower respiratory tract up to the pharynx to be expelled.

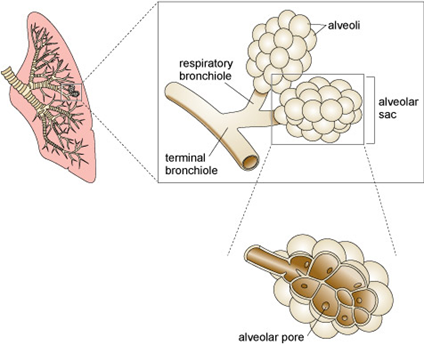

Finally, the air enters small sack-like structures called alveoli (singular: alveolus). It is here where the oxygen is transferred into the blood and the waste gas, carbon dioxide is transferred out of the blood (Figure 2).

Figure 2. A drawing of a lung (pink) with a bronchus and branching bronchioles within the lung.

Gaseous exchange

Gaseous exchange refers to the transfer of oxygen and carbon dioxide between the air and blood.

The walls of the alveoli are only one cell thick. This is also true of the walls of the tiny capillaries surrounding the alveoli (Figure 3) therefore carbon dioxide and oxygen can move by diffusion.

When oxygen rich air is breathed in, the oxygen diffuses into the red blood cells (erythrocytes) which deliver the oxygen to all the other cells of the body. Carbon dioxide, returning from the body in the blood, diffuses from the red blood cells into the alveolar space and is breathed out.

The capillaries are so tiny that they only allow one blood cell at a time to pass through, slowing the blood flow and allowing time for gaseous exchange.

Figure 3. Gas exchange at (a) the lungs and (b) the tissues, showing the partial pressures of the gases, PO2 and PCO2.

An important feature of gaseous exchange is that gases diffuse from a region of high concentration to a region of lower concentration, or in other words, they move down their concentration gradient. The convention is to use partial pressures when describing the concentration of respiratory gases and the units shown in Figure 3 are millimetres of mercury (mmHg).

What is a partial pressure? The partial pressure of a gas is the proportion that gas contributes to atmospheric pressure. At sea level, the average atmospheric pressure is 760 mmHg – so, if the partial pressure for oxygen at sea level in inspired air is 160 mmHg, then the percentage of oxygen in inspired air can be calculated by dividing 160 mmHg by the atmospheric pressure and multiplying the result by 100:

(partial pressure of the respiratory gas/atmospheric pressure) x 100 = percentage of the gas

(160 mmHg/760 mmHg) x 100 = 21%

|

What is the percentage of carbon dioxide gas in inspired air? |

|

What is the percentage of carbon dioxide gas in expired air? |

The role of the diaphragm

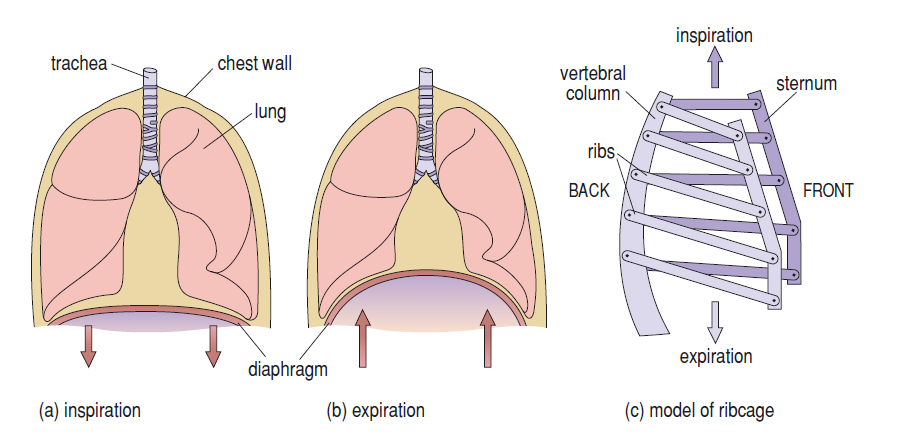

The expansion and contraction of the lungs is controlled mechanically by the diaphragm and the intercostal muscles (Figure 4). The intercostal muscles are located in the ribcage (see Figure 1). The diaphragm is a large dome-shaped muscle that sits underneath the lungs.

Figure 4. The mechanics of inspiration and expiration. (a) The diaphragm flattens and moves downwards, so increasing the thoracic capacity and allowing air to enter the lungs. (b) During expiration, the diaphragm curves upwards and the thoracic capacity is reduced. (c) A model of the ribcage as a side view. During inspiration, the ribs and sternum move upwards and outwards; during expiration, the ribs and sternum move downwards and inwards.

|

Activity |

|

Part 1 Place your hands onto your ribcage. Now, take a deep breath in. What happens to your ribcage? You should find that your ribcage moves upwards and expands outwards as the air enters your lungs. Movement of the diaphragm and intercostal muscles acts to expand the size of the thoracic cavity drawing air into the lungs. Part 2 Now blow the air out of your lungs. What happens to your ribcage? You should find that your ribcage moves downwards and retracts inwards as the air leaves your lungs. Relaxation of the intercostal muscles and diaphragm reduces the size of the thoracic cavity. The ribcage, diaphragm and lung tissue itself return by elastic recoil to their original pre-inspiratory positions. The consequent retraction of the chest wall forces air out of the lungs. |

Lung function

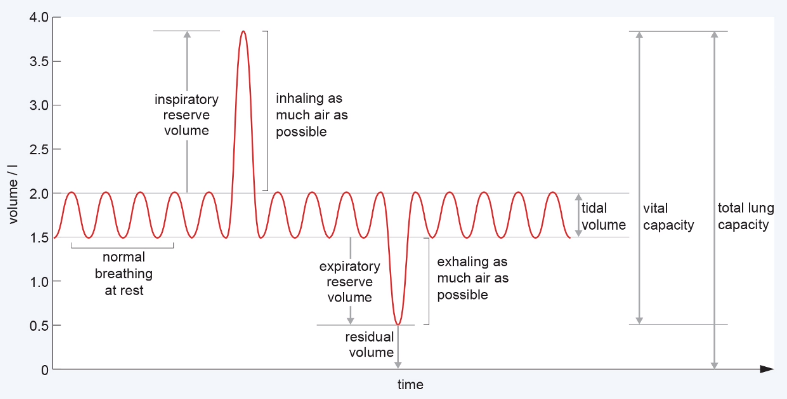

Changes in lung tissue caused by age, disease or smoking can affect the capacity of the lungs to hold and exchange air. Lung capacity is calculated from the volume of air that is exchanged during normal and forceful breathing. The volumes that are used to calculate total lung capacity are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Graph showing the volume of air moving in and out of the lungs during normal and forceful respiration.

- Tidal volume is the amount of air moved by your lungs when you are breathing normally at rest.

- Inspiratory reserve volume is the extra volume breathed in during forceful inhalation.

- Expiratory reserve volume is the extra volume of air breathed out during forceful exhalation.

- Residual volume is the amount of air left in the lungs after a forceful exhalation.

- Vital capacity is the total amount of air you can breathe in after you have forcefully exhaled.

- Total lung capacity is the total lung volume.

|

Using the information in the spirogram shown in Figure 5 what volume is the vital capacity? |

|

|

Compliance of lung function

The ease with which the lungs and pleura expand and contract, based on changes in pressure is called compliance. Low lung compliance means that the lungs and alveoli are ‘stiff’, so a higher-than-normal pressure is needed to get the lungs to expand and contract. It can result from fibrosis of the lungs due to prolonged inhalation of small particles such as asbestos, tobacco smoke, indoor cooking smoke, car exhaust fumes or coal smoke.

Prolonged exposure to tobacco smoke and indoor cooking smoke can cause inflammation of the lungs (chronic bronchitis) and damage to the alveoli (emphysema) – a condition called Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD). This makes it more difficult to breathe, reduces the elastic recoil properties of lung tissue and reduces the lung respiratory surface area available for gaseous exchange.

Measuring lung function using spirometry

Lung function can be measured using a spirometer – a simple and inexpensive device that measures the flow and volume of expired air. A typical test involves blowing out into a spirometer as hard as possible until the lungs are empty (this is explained further in the introductory video located on the Spirometer application homepage).

The forced vital capacity (FVC) is calculated as the total volume of air that can be forcefully blown out of the lungs in one expiration (one breath).

Peak expiratory flow (PEF) measures the maximum speed at which air is forcefully expired (litres per second).

The forced expiratory volume 1 (FEV1) is the amount of air that is forcibly blown out within the first second of a forced expiration.

Plotting the FVC and PEF values generates a spirograph, which you will produce when you use the spirometry application.

The FEV1/FVC ratio (normally expressed as a percentage) is used to evaluate lung function. In healthy individuals, the FEV1/FVC ratio is approximately 0.8, meaning that 80% of total volume of air is blown out within the first second. A value of less than 70% indicates that lung function is impaired.

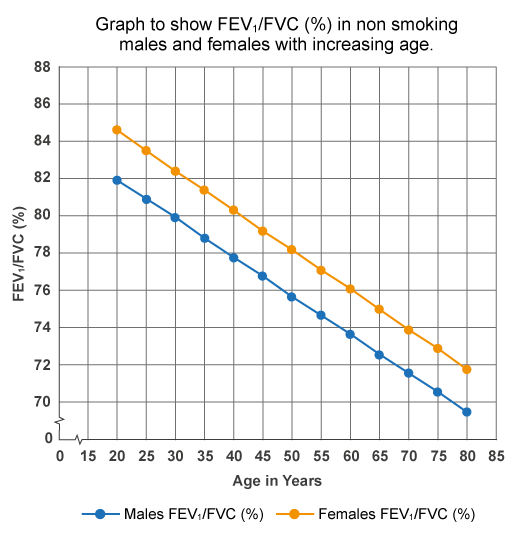

Normal lung function is dependent on an individual’s age, height, sex, ethnicity and general fitness. For example, Figure 6 shows how lung efficiency (FEV1/FVC ratios) decrease with age for both men and women.

Figure 6. A graph showing the FEV1/FVC ratios expressed as percentages for healthy non-smoking men and women against age.

|

Look at Figure 6. Which two statements are correct about lung function with age in both men and women? a) Lung function stays the same across all ages in males and females b) Lung function increases with age in males and females c) Lung function decreases with age in males and females d) Lung function is slightly lower in males than females across all ages e) Lung function is slightly higher in males than females across all ages |

When lung function is impaired, the PEF, FEV1, FVC and FEV1/FVC values can be used to help determine the cause of the dysfunction; for example, decreased lung volume due to lung cancer, asthma, pneumonia and COPD.

Previous: Lesson objectives Next: Practical activity