Background (Calorimetry: energy in food)

Background

Chemical substances in food

The body needs food for energy, movement, repair, growth and reproduction. The combination of foods regularly eaten by an individual or a population, referred to as their diet, has a major impact on health. To stay healthy, the body needs a diet that provides the right balance of six categories of nutrients, the chemical substances in food that provide the body with the nourishment it requires:

- carbohydrates

- fats

- proteins

- vitamins

- minerals

- water

Dietary carbohydrates, fats and proteins are collectively termed macronutrients because the body requires them in relatively large amounts. Carbohydrates and fats typically provide the body with most of its energy. Proteins can also provide energy, but more importantly they are required to provide the building blocks needed to build thousands of new proteins with essential roles in body processes and structures.

Vitamins and minerals are referred to as micronutrients because they are required by the body in very small amounts. They do not provide energy, but they are essential to build and maintain structures in the body.

|

Which minerals are essential for the body? |

As food passes through the alimentary canal, complex macronutrients are broken down into smaller components. This allows them to be absorbed by the cells lining the gut. The fate of these molecules we obtain from food depends on the needs and demands of our bodies. Some molecules, such as glucose, are used to provide energy. Other molecules, such as amino acids, are used to build and repair cellular structures and tissues.

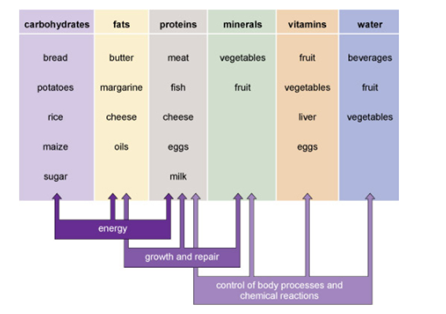

Figure 1 summarises the main roles in the body of the six different categories of nutrients and reminds you of some of the foods that provide them.

Figure 1. A summary of the six different categories of nutrients, their main roles in the body and some of the foods that provide them.

Carbohydrates

Carbohydrates are a group of organic molecules that occur in living organisms and include sugars, starch and cellulose. Most people obtain the majority of their food energy from starch-rich foods, such as flour, potatoes, rice, pasta and pulses (peas, beans and lentils).

The general formula for simple carbohydrates, which relates the relative proportions of different atoms found in the molecule, is Cn(H2O)n, where n is the number of carbon atoms.

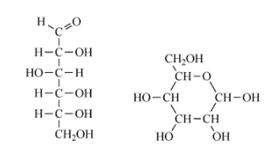

Most common simple sugars have five or six carbon atoms. These carbohydrates are known as monosaccharides as they are made of one sugar unit. Glucose is an example of a simple sugar, and it is vital for human life as our primarily source of energy. It also plays an essential part in the metabolism of plants and is the main product of photosynthesis. Glucose has the formula Cn(HnO)n and can adopt two distinct types of structure: a straight-chain form or a cyclic form (as shown in Figure 2).

Figure 2. Structures of glucose: (a) straight chain for of glucose and (b) cyclic form of glucose.

Inside cells and organisms where glucose is dissolved in water, it adopts a cyclic form. The same structure is observed for other monosaccharides (such as fructose and galactose) when dissolved in water.

|

Which are the functional groups in the straight chain glucose? |

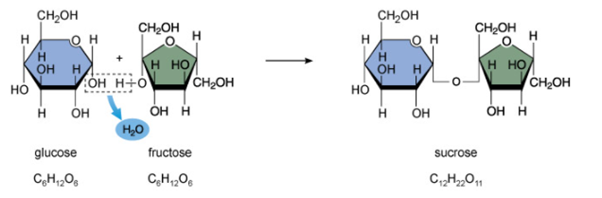

Monosaccharides are the basic building blocks of all larger carbohydrates, which are built up by linking together two or more monosaccharide units by covalent bonds. Figure 3 shows a glucose molecule and a fructose molecule linking to form sucrose in a chemical reaction called a condensation reaction, because it releases a molecule of water.

Figure 3. Glucose and fructose linking by covalent bonds to form sucrose (sweet table sugar). Monosaccharides are represented in a simplified way in which the ring structures are a hexagon (six-sided) shape for glucose and a pentagon (five-sided) shape for fructose.

Fats and oils

Fats and oils fit into a class of molecules collectively called lipids. These are organic compounds that have a slippery or greasy feel to the touch, and they are not soluble in water. Although sometimes dietary fats are regarded as unhealthy, in fact lipids perform many important roles in the body. Lipids provide a source of energy and a way of storing it, they help with the digestion and transport of substances that dissolve in fat, they insulate the body and they are important components of cell membranes.

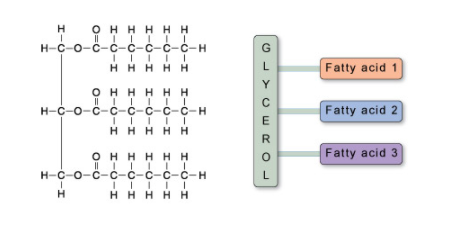

Dietary fat is composed of molecules called triacylglycerols (you may also see them referred to by triglycerides). A triacylglycerol molecule is made up of three long molecules called fatty acids, attached to another molecule called glycerol (Figure 4).

Figure 4. A molecule of triacylglycerol showing the three fatty acids covalently linked to a glycerol molecule.

Cells can use dietary triacylglycerols as a source of energy. They are broken down in the gut into individual fatty acid chains and delivered to cells in the blood circulation. If they are not needed immediately, the fatty acids are recombined with glycerol and stored as triacylglycerols inside adipocytes (fat cells).

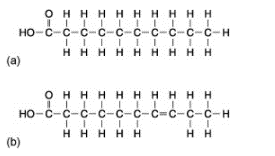

In food labelling, fats are often categorised into saturated fat (or just saturates) and unsaturated fats. Saturated fats tend to be solid, animal-derived fat, for example the fat in meat. Unsaturated fats tend to be liquid oils derived from plants, for example corn oil. In saturated fats, all the covalent bonds between the carbons in the fatty acid chains are single bonds. In unsaturated fats, on the other hand, there are one or more double bond carbons in the fatty acid chains. These fats are therefore ‘unsaturated’ with hydrogen (some of the carbons are making C=C double bonds instead of C–H bonds).

Figure 5. Example of (a) a saturated and (b) an unsaturated fatty acid chain

|

Why is eating lots of saturated fats bad for your health? |

Proteins

The body’s cells constantly synthesise new proteins using amino acids obtained from food. Each type of protein is composed of several hundred amino acids linked together in a particular order or ‘sequence’. There are twenty different amino acids commonly occurring in animal proteins.

|

In a body cell, what is the name of the structure (located in the cytoplasm) where protein synthesis takes place? |

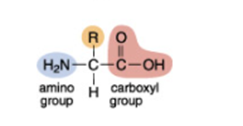

The amino acid with the simplest chemical structure is called glycine (shown in Figure 6). In glycine the R group is a hydrogen atom, but the other amino acids have a larger R group composed of several atoms. Each type of amino acid has a different chemical structure, but they all have the same chemical ‘groups’ attached to either end of the molecule. At one end is a group of atoms called an amino group (NH2, highlighted in blue in Figure 6) and at the other end is a different group of atoms called a carboxyl group (COOH, highlighted in pink in Figure 6). These two chemical groups are crucial in the process of joining amino acids together to make proteins.

Figure 6. Structural formula of glycine.

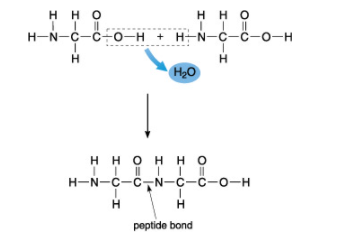

The bond that forms between amino acids is called a peptide bond and links the amino (NH2) group of one amino acid to the carboxyl (COOH) group of another amino acid, forming a new covalent bond between the two amino acids and releasing a water molecule (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Two amino acids link together by covalent bonding to form a dipeptide

You may have noticed that this a condensation reaction (meaning water is released) similar to the one that links monosaccharides together.

Food and energy

In science, energy is usually described as the capacity to produce change in a system. For example, one chemical substance can be changed to another by the energy transferred during the breaking and making of chemical bonds. The life of an organism is sustained by energy from the environment in the form of nutrients. Chemical energy obtained from the digestion of food molecules can be used in chemical reactions in the body that build new molecules, produce heat or cause movement.

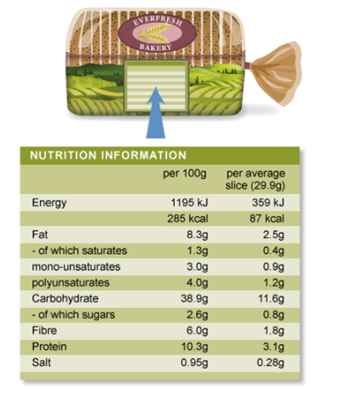

The energy provided by food is measured using an SI unit of energy called the joule (which has the symbol J). You may have noticed that packaged foods usually have a nutrition information label showing the total energy provided by the food in kilojoules (kJ) per serving or per 100 g.

However, a non-SI unit of energy called the calorie (cal) is commonly used in nutrition. A calorie is equal to the amount of energy per unit mass required to raise the temperature of 1 g of water by 1oC. One calorie is equivalent to 4.184 J. When reading nutrition labels on food packaging, you will see food calories expressed as kilocalories or Cal (sometimes denoted with a capital C).

1 nutritional calorie (Cal) = 1 kilocalorie (kcal) = 1000 calories (cal) = 4184 joules (J)

Figure 8. Food labelling for brown bread.

|

How many kilojoules are in a Calorie? |

The total amount of energy made available when food is metabolised in the body depends on the combination of nutrients the food contains. Table 1 shows the energy density – the average energy available per gram – of fat, protein and carbohydrate.

Table 1. The average amount of available energy in 1 gram of different types of macronutrients

|

Macronutrient |

Energy / kJ g-1 |

Energy / kcal g-1 |

|

Fat |

37 |

9 |

|

Protein |

17 |

4 |

|

Carbohydrate |

17 |

4 |

|

How does the energy available of 1 gram of fat compare to that of protein or carbohydrate? |

|

Compare the food nutrient content shown in the food labels of pistachio nuts and a baked corn snack (Table 2). Which food shows the highest energy content per gram?

Table 2 Food nutrient content on food labels

|

||||||||||||||||||

Food calorimeters

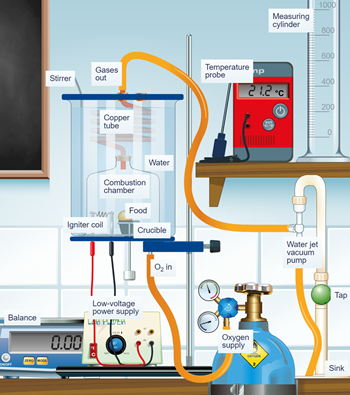

Figure 9 shows the simple food calorimeter that you will use in this practical to find the amount of energy stored in some food. The basic principle of this instrumentation is that energy transferred during the combustion of food (as heat) causes the water in the surroundings to increase its temperature.

Figure 9. Simple food calorimeter

The instrument consists of a borosilicate water jacket surrounding an integral combustion chamber which is opened at the base. The combustion chamber is connected to a copper spiral heat transfer tube through which products of combustion will be drawn out using a vacuum pump. A wire stirrer and a temperature probe are fitted through the lid of the borosilicate jacket. The base of the calorimeter comprises a metal disk that forms the floor of the combustion chamber with some clips to hold the water jacket securely. It has an inlet for oxygen supply for a more efficient burn of food and a couple of pillars carrying the low voltage igniter coil. There is also a moveable crucible support on the base, enabling the crucible to be raised to the igniter coil from outside the calorimeter.

When the ignition coil gets hot, it ignites the food in the crucible and the oxygen flowing inside the combustion chamber ensures that the food continues burning. The gases produced in the combustion of food rise through the copper coil and heat the known volume of water inside the borosilicate jacket. The water jacket acts as a heat exchanger and as an insulator of the combustion chamber. The manual stirrer will ensure uniform temperature measurements.

|

Is the combustion of food an exothermic or endothermic reaction? |

|

Which gases are produced in the combustion of food? |

To calculate the energy transferred from the combustion of food to the water (q) you will use the equation:

q = m c ΔT

where m is the mass of water in the conical flask, c is the specific heat capacity of water (4.18 J g-1 oC-1) and ΔT is the increase in the temperature of water.

Remember that the density of water is 1 kg/l so if you are using a volume of 100 ml of water in your experiment, this volume is equal to 100 g of water.

|

In a food calorimeter, a small amount of brown seeded bread was burned and was used to heat 1000 ml of water at an initial temperature of 21.5°C. When the temperature of water increased to 23.2°C, the mass of bread burned was 0.62 g. Calculate the experimental number of kilocalories released per 100 grams of food. |

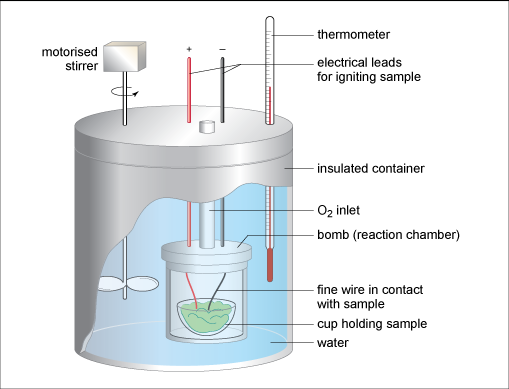

In industry, energy from food combustion is usually measured using more sophisticated instruments such as a bomb calorimeter which is shown in Figure 10. A known mass of the combustible sample (in solid or liquid phase) is placed in a sealed thick-walled metal reaction chamber (the ‘bomb’) which has an oxygen inlet. The term ‘bomb’ comes from the possibility of these combustion reactions being vigorous releasing heat very rapidly like explosions. The bomb is immersed inside an insulated water bath with a motorised stirrer and thermometer. Electrical leads connect to a heating coil which heats and ignites the sample, and the heat evolved from the combustion is transferred to the water raising its temperature. A bomb calorimeter works at constant volume and these robust devices are built to withstand large pressures produced from the combustion gases.

Figure 10. A bomb calorimeter

Bomb calorimeters need to be calibrated before their use to determine the heat capacity of the entire calorimeter (including bomb, water, thermometer, stirrer) using a calibration sample of known heat given off value. Each instrument will have a different value for its heat capacity. This calibration step allows for very accurate results.

It is important to understand that our bodies do not metabolize food in exactly the same way as a food is burned in a calorimeter; it is a more complex process. There are certain components of food (such as fibres) that despite burning in a calorimeter we are not able to digest.

Previous: Lesson objectives Next: Practical activity