1.3 Een: where Scots is seen in written form

There is a long tradition of literacy in the Scots language passed on from the Middle Ages to Robert Burns in the eighteenth century down to the present day. There are a number of different kinds of Scots language texts which are widely read in Scotland today.

Arguably, the most significant increase in availability and quality of Scots language publishing in the last fifteen years has been seen in books for children. Itchy Coo, an imprint of Black & White Publishing, was co-founded by this present writer and writer James Robertson with the aim of producing 'Braw Books for Bairns o Aw Ages'.

Since 2002, Itchy Coo [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] has published over 60 titles and sold in excess of 250,000 books, the majority of these to schools. Itchy Coo's most read titles include King o the Midden, Blethertoun Braes, A Wee Book o Fairy Tales in Scots and Scots translations of Roald Dahl novels, Julia Donaldson’s The Gruffalo and J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stane.

Today a new generation of young readers has access in education and at home to a wide range of books and reading opportunities in Scots. It is also interesting to note the enduring popularity of The Broons and Oor Wullie cartoons written continuously in Scots since the 1930s. Visit the National Library of Scotland’s Oor Wullie website to explore different volumes of the cartoon published over the years.

Many Scottish writers continue to choose Scots to express their view of the world. Some of the best known poets and authors writing in Scots today are Billy Letford, Hamish MacDonald, Janet Paisley, Sheena Blackhall, Alan Bissett and Kathleen Jamie. There is also an established and continuing tradition of translating from other languages into Scots. Among the most notable practitioners of this art form stand Brian Holton translating Chinese poetry into Scots and Gordon Hay translating the New Testament and Charles Dickens into Doric.

National competitions such as the James McCash Poetry prize and the Wigtown Scots Poetry Prize receive annually a considerable volume of high-quality writing in Scots. And it is significant that many young people are finding their own voice in Scots poetry and prose. A showcase of new Scots literature by young writers is available to read here: http://skoosh.scotshoose.com/

Since the Referendum on Scottish Independence in 2014, written Scots has been seen more regularly in the print media and online. The National newspaper has published a weekly Scots column since January 2016. Bella Caledonia, a pro-independence online publication, has also been frequently posting articles in Scots.

Social media is another platform where people choose to write and communicate in Scots. The 'Scots Language Forum' on Facebook encourages members to write solely in Scots. Police at a station in Fife - the council area with the second highest number of Scots speakers after Glasgow - have recently been engaging with their community in Scots on Twitter. Many people, all across Scotland, will use Scots when writing instant messages to one another. Comments posted on places like Facebook or other discussion fora can also be full of Scots language.

We can also find written Scots in the community as Scots language is embedded in the urban and rural place names of Scotland. Scots is seen today in the names of streets in many Scottish towns, for example, Kirk Vennel ('Church Alley') in Irvine, Lang Stracht ('Long Straight') in Aberdeen, Gallowgate ('road to the gallows') in Glasgow, Tolbooth Wynd ('Town hall Lane') in Leith and The Sinderins ('parting of the ways') in Dundee.

Although many Scots street names have avoided anglicisation, it is worth considering the fate of Baxter's Wynd in St Andrews which a council decision rendered 'Baker's Lane'. However the town of Keith in Moray has recently positively discriminated in favour of Scots by assigning words like sodger ('soldier'), fairmer ('farmer') and ploo ('plough') to previously unnamed streets.

The Scots language is very much in evidence in the landscape of Scotland. Law (hill), knowe (rounded hill), brae (slope), burn (stream) and linn (waterfall) are just a sample of the huge number of Scots words found in place names all over the country.

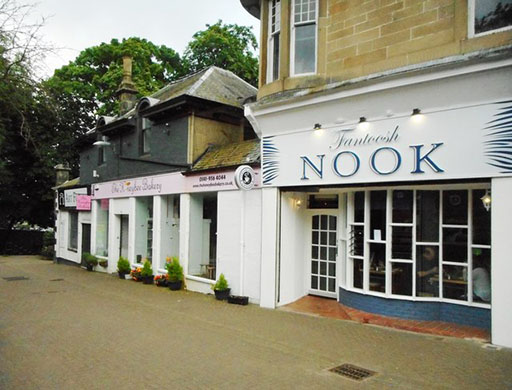

Although not an entirely new phenomenon, the use of the Scots language by business owners and the general public has become more widespread in recent years. The last decade has seen a growing trend by business and store owners of incorporating the Scots language in shop names or products.

Several firms have promoted positive Scots words like guid (good), braw (fine or excellent) and fantoosh (fancy) as their company name.

There has been a corresponding increase in use of the Scots language in public signage. From homeowners giving their house a Scots name, to people writing Scots in advisory or information signs, there is a greater visibility of written Scots today in communities around Scotland. This can be seen in signs such as Oor Hoose, Nae smokin and Weet pent. Edinburgh Castle has recently added Scots to its languages inviting visitors to Come awa ben.

Campaigns have also made effective use of Scots to engage the public. Two of the most memorable are Scrap Trident's slogan Bairns Not Bombs and Shetland Amenity Trust's long-running environmental awareness initiative Dunna Chuck Bruck (Do not litter).

Activity 6

Now scan the text in this section, Een: where Scots is seen in written form, again and select your personal ‘Top Five’ examples of written Scots language in Scottish culture today.

When ranking these examples, think about the impact each might have on making Scots a more prominent aspect of Scottish life and normalising Scots as an indigenous language of Scotland.

1.2 Lugs: where Scots can be heard