Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 19 April 2024, 5:51 AM

Course content

Introduction

Transcript

Hello, and welcome to this free course on deaf awareness education. My name is J’enna Flynn and I’m a British Sign Language Level Six accredited signer and a professional special tutor for deaf and hard of hearing people. In my experience of working in this field, there is often a lack of information on the subject. This course has been written for employers, educators, and anyone who interacts with deaf or hard of hearing people. It is designed to give you an introduction to the issues that the deaf face and explain some strategies in enabling communication. I hope you enjoy the course. Thank you.

Welcome to this free course, Deaf awareness education. This course introduces the concept and definitions of deafness. It is designed to offer an insight into the communication barriers that deaf and hard of hearing people may face and offer solutions for how to overcome them to provide an accessible learning environment.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course you will:

have an awareness of the various facts and figures of deafness

understand how to communicate with deaf people

be aware of the barriers deaf learners may face within their studies and in everyday life

use this information to create a more accessible learning environment.

1 Deaf awareness

1.1 Definitions

The concept of deafness encompasses a broad spectrum of types or deafness and severity. An individual can be born deaf or they may experience hearing loss during their life through illness, exposure to loud noises, or as a consquence of old age. Before going any further, it is important to define the key definitions of deafness.

Deaf –‘Deaf’ written in a capital D is usually used to refer to those who associate themselves with the Deaf community. They have a strong Deaf identity and use BSL as their preferred language.

deaf – ‘deaf’ with a lower case ‘d’ is typically used as a medical reference to indicate a person is deaf.

Hard of hearing– is used when an individual has partially lost their hearing.

Deafened – is usually associated with an adult who has lost their hearing over time.

Deafblind – is used when a person has some degree of both hearing and sight loss.

Tinnitus – Tinnitus (pronounced ti-ni-tis), or ‘ringing in the ears’, is the sensation of hearing ringing, buzzing, hissing, chirping, whistling, or other sounds. The noise can be intermittent or continuous, and can vary in loudness.

Activity 1 Reading the signs

What would be some of the signs that would indicate that a person has a degree of hearing loss?

Answer

Some of the signs that would indicate that somebody has difficulty hearing are as follows. The person might:

- study your mouth while you are talking to them (lip-reading)

- not respond or not take any notice when you are talking to them

- use sign language as their preferred communication method

- misunderstand you when you are talking

- wear a device such as a cochlear implant or hearing aid

- ask you to repeat yourself

- laugh inappropriately, if they feel embarrassed to ask to you to repeat again.

It is important to recognise that there are many differences in the severity of the hearing loss. It is also important to appreciate that some individuals may feel confident about acknowledging their deafness whereas others may be less forthcoming.

…On average, it takes someone 10 years to not only admit that they have a hearing loss and, more importantly, do something about it! This is predominately due to the elder generation being in denial of having a hearing loss. |  |

1.2 Facts and figures on deafness

The following facts and figures will help you put your learning into context. You can then apply what you have learned from this course into everyday life should you meet a deaf or hard of hearing person or if you need to create a learning environment for an individual or group of deaf students.

Activity 2.1 Numbers

a.

12 million

b.

9 million

c.

19 million

The correct answer is a.

Activity 2.2 Numbers

a.

151,000

b.

90,000

c.

500,000

The correct answer is a.

As you can see in Activity 2 there is a large proportion of the UK population who have a hearing loss. If we take the population of the UK to be around about 67 million people, it would be true to say that 1 in 6 people in the population have a hearing loss.

According to figures published by Action on Hearing Loss and National Deaf Children's Society (NDCS) there are around 50,000 children with a hearing loss.

Of course, not everybody who has a hearing loss will learn sign language. According to the British Deaf Association (BDA), there are around 151,000 Deaf individuals who use British Sign Language (BSL) in the UK.

1.3 Deafness at school

The UK government recently released a report analysing deaf children’s progress within the education system, particularly focusing on schools. It was reported that deaf children’s GCSEs were ‘particularly concerning’. There was also a 2% decrease in the number of Teachers of the Deaf (ToDs), which has undoubtedly had a great impact on the education of deaf children. These figures are the consequences of funding cuts.

ToD are particular important as they aid in a deaf child’s learning development from a young age – helping them to acquire English as a second language and providing them a bridge between languages.

The report also concluded that 61% of deaf children are leaving primary school having failed to achieve the expected standard at reading, writing and mathematics compared to 3% of children with no identified special education need.

We can all read the reports on how deaf students are underachieving in comparison with their hearing peers. However, what is important is that we, as professionals, parents, and community members work together to support those with a hearing loss within the education sector, ideally starting before primary school age.

With regards to the report, there are many reasons for the figures given. In my experience, having worked in the education sector, I believe it is down to a lack of resources: a lack of ToDs, speech and language therapists, communication support workers, British Sign Language (BSL) interpreters and other crucial resources.

I might add also that, although tinnitus isn’t always regarded as a hearing loss, the same strategies could be applied. Those with tinnitus tend to have it at different levels severity: for example, some may notice it when trying to go to sleep, while others may hear it all the time. Whatever the severity, we must also ensure that we support people with tinnitus too.

2 Hearing loss and the ear

Activity 3 How loud?

Match these sounds to the decibels (dB).

Using the following two lists, match each numbered item with the correct letter.

35dB

110dB

120dB

60dB

10dB

a.1 Whisper

b.2 Headphones

c.4 Vacuum cleaner

d.5 Birdsong

e.3 Jet engine

- 1 = a

- 2 = b

- 3 = e

- 4 = c

- 5 = d

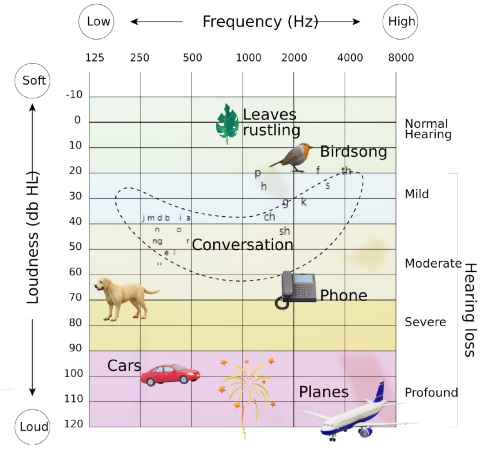

Figure 4 shows the different stages of hearing loss on the audiogram and what sounds are affected depending on the hearing loss.

An audiogram is used to illustrate how much you can or can’t hear. Usually this test will be undertaken by an audiologist.

The numbers presented are decibels (dB). They illustrate the noise volume.

| ...workers in noisy environments must wear ear defenders? Your hearing can be significantly affected when listening to sounds between 90dB and 110dB for long and frequent periods of time. If you are surrounded by 120 -140dB of sound you will damage your hearing instantly. Once the damage is done there is no going back! |  |

3 Different types of hearing loss

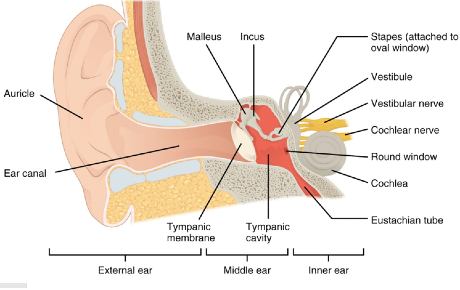

The type of hearing loss incurred depends on which part of the ear is affected.

I would suggest the majority of hearing loss is a ‘Sensorineural’ loss. This is caused by a malfunction in the cochlear. The cochlear is situated in the inner part of the ear.

The other types of hearing loss are: Conductive (when there is damage in the middle ear) and Multi Conductive and Sensorineural which would suggest the middle and inner ear are impaired.

Activity 4: Communication tactics

If you were to meet someone who is deaf or hard of hearing how should you communicate with them? Make a list of the sorts of things you should and shouldn’t do.

Answer

Things you should do:

- Get the person’s attention

- Face the person at all times

- Use gestures and body language

- Take your time/slow down your speech

- Switch off TVs, radios or anything else that might impere hearing

- Use an expressive face.

Things you shouldn’t do:

- Say ‘it doesn’t matter’

- Stand in a position where they can't see you properly

- Shout

- Cover your mouth

The tactics discussed may help communicating with deaf people. For those people who are profoundly deaf or struggle to communicate using English it may be that they are most comfortable communicating in sign language. Section 4 considers British Sign Language in more detail.

4 British Sign Language (BSL): an introduction

Origins

BSL is considerably different when compared to English. It is a language in its own right. It began with Mary Brennan undertaking extensive research in 1970. She worked alongside William Stokoe who was the founder of American Sign Language (ASL). Following her research, Brennan started to understand the structure of sign languages: their form, style. and how they can so eloquently paint visual pictures. It was from the linguistics of ASL that BSL was developed.

It took from 1970 with the hard work of creating ‘The BSL Dictionary’ to 2003 for the government finally to recognise British Sign Language as a language in its own right.

Unlike other countries, such as India, New Zealand and America, the UK still falls short when it comes to supporting the Deaf community.It has taken years of campaigning for the language to be recognised, to have subtitled cinema showings, and to ensure that there are BSL interpreters on TV shows including the news. In a recent example, the UK government did not always have a BSL interpreter present to sign while key updates were being delivered at the daily press conference during the COVID-19 pandemic. (Other areas of the UK, such as the Scotland government, were much better at making concessions for the Deaf community.) In short, there is still a long way to go in the UK.

Language difference explained…

Many people assume that BSL is simply a version of English that uses visual representations of words instead of sounds. This is incorrect. They are in fact two different languages with two completely different language structures as we will see later in this section of the course.

It is worth considering this if you have a deaf student, employee or family member as it may help you to understand why there is a communication barrier and how you can help reduce this.

4.1 How does BSL differ?

Sign languages across the world are thought to be very picturesque: beautifully projected by shapes formed by the hands. Every element of that sign, the handshape, movement and location of that sign is a unique linguistic feature: not one that the spoken language can easily replicate.

As part of Deaf Awareness Week in 2019, The Open University Students Association created a series of video tutorials to introduce British Sign Language. If you’d like to see how to sign basic words and phrases then this is a useful resource to get you started.

The linguistics are so very different to English: ranging from the different types of timelines and the listing items to the all-important placement, down to the Non Manual Features(NMFs)/facial expressions.

With the linguistics of English, each word is broken down into morphemes and phonemes. The base word, which changes mood depending on which suffix or prefix is added. Don’t forget the awful confusion of verbs: are they irregular verbs, the past, present, future discombobulation of the tenses along with the who’s who pronouns.

With such an array of language differences, is it unsurprising that deaf people struggle with English.

4.2 English word order

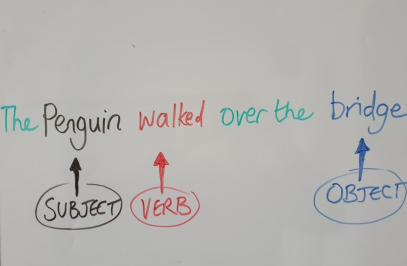

Let’s take a generic sentence and compare how languages differ in their structures.

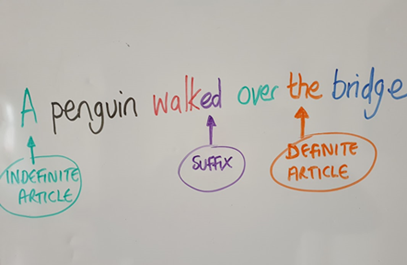

The sentence example: ‘The penguin walked over the bridge’.

In English, we would say exactly that: ‘The penguin walked over the bridge’. This is word order in English: Subject, Verb, Object.

Looking at the same sentence in a little bit more detail:

In this sentence ‘A’ and ‘The’ are articles. They illustrate what type of noun they are. Using this sentence as an example, ‘a’ is before the word ‘penguin’ to show that it would be any penguin walking over the bridge. The word ‘The’ being used before the word ‘bridge’ shows that it is a particular bridge: the definite article.

Looking at the word ‘walked’, placing the suffix ‘-ed’ at the end of a verb signifies that it is in the past tense.

By looking at the structure of this sentence at a high level, we can see how complex the English language can be and how every part of the sentence informs the meaning.

4.3 BSL word order

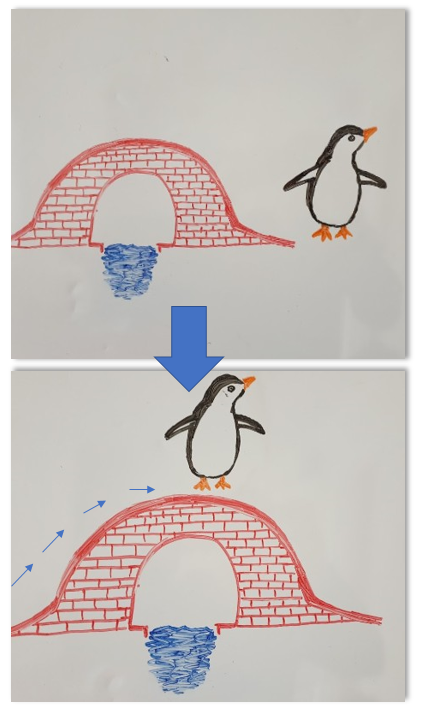

Looking at how BSL differs from English, lets take the same sentence used earlier and see how it is created in BSL.

When forming sentences in BSL, it would be best to think of it as painting a picture on an empty canvas. So if you were to take the same sentence, what would you paint on your canvas first?

A key difference is that the word order in BSL is Object, Subject and Verb. - O,S,V. You sign this by placing the bridge first, then the penguin (point) at the subject and then sign the subject walking over the bridge.

When signing, you can see how English differs greatly. Signing is a more visual and sometimes a more blunt way of expression. It differs greatly from English in so many linguistics aspects.

4.4 What’s the word order difference?

In English if we were to talk about the penguin, we would use pronouns such as ‘It’ or even ‘he’ or ‘she’ if we know the gender of the penguin. BSL does not use pronouns.

In BSL, a subject is usually introduced with their name and information about them. The subject is then ‘placed’ within the signing space and would be referred to by pointing at the subject.

In regards to tenses, these are represented in BSL by timelines. For example, you would use a timeline indicating the past, present and future. There is also a growth timeline and a numerical timeline.

Suffixes are not included in BSL. When denoting plurals with the suffix ‘-s’, BSL replicates this by signing the object multiple times.

5 What to do next?

Having understood the language difference and that BSL is a language in it’s own right, how do you use this information going forward?

Whether you work within the education sector, have a deaf employee or know someone who is deaf/hard of hearing, it would be good to take this knowledge with you.

Use it to help make communication easier and accessible to all. Far too many assume that a deaf person can read perfect English, including whatever jargon that is thrown at them. Please recognise that this is not always the case.

To offer you some further insight the following activities are a series of short scenarios to get you thinking of what you could do to help.

5.1 Supporting a deaf student

Activity 5: Alex in the classroom

Alex is in his Year 6 classroom on a Monday afternoon. His class is noisy and bosterous as usual. He’s finding it a challenge to complete the task in front of him: not quite sure how to answer the questions. Although it was explained by the teacher, a lot of disruption occurred and Alex didn’t have the confidence to ask for the information to be repeated.

What could the teacher or tutor do in this scenario to help Alex? What measures could the school put in place to ensure that deaf and hard of hearing students don’t struggle in this way? Write down your thoughts.

Discussion

As a deaf pupil in a mainstream school, trying to access your education and create a social circle can be a daunting challenge.

Ideally, the school would have access to a group of tutors that are able to sign. Having deaf awareness can help those students feel comfortable to comunicate to their tutors freely.

Resources such as a signer, notetaker, Teacher of the Deaf and Speech and Language therapist are invaluable for a deaf or hard of hearing student. Having access to these professionals right from preschool to degree level makes a difference to being able to access the world around them. Far too often students have to endure difficulties due to not having access to these resources.

To help students such as Alex in the classroom, teachers could provide information in advance such as key words, a visual glossary, and generally supply additional information in order to support the deaf. In fact, a lot of this is not specific to deaf students and writing with deaf students in mind can be helpful to ensure that teaching resources are accessible for all students.

5.2 Working with a deaf employee

Activity 6: Zahara’s struggles at work

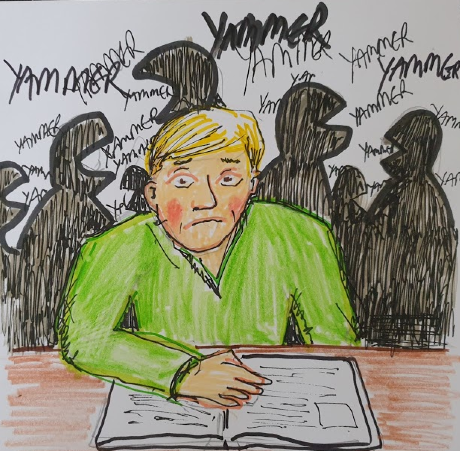

Zahara is profoundly deaf. She works in a fast-paced office which operates a hotdesk policy. More often than not, nobody says ‘hello/good morning’ etc to Zahara. On this particlar day, Zahara and the team are called into a meeting at short notice. The meeting makes no sense as everyone is speaking simultaneously so it is extremely difficult to lip-read. In the end Zahara gives up. As a result, Zahara has no idea what’s going on and what to do.

Write down your thoughts on this scenario and what you could do to help as a manager/colleague in your place of work.

Discussion

Having a deaf employee within your team can be incredibly isolating for the individual. Imagine not really having anyone to speak to within that environment, not being able to ask how your weekend was or how you’re getting on at work.

Learn some basic BSL and even the key jargon words. Doing this not only helps your team member to feel included, but also helps them to understand what you’re trying to communicate to them.

Write in plain English. This helps the deaf person to understand the message you are trying to relay to them.

Use other resources, such as an interpreter or a notetaker. Using an interpreter will help eliminate that communicate barrier, allowing for smooth communication to take place. Notetakers can be useful for those who are hard of hearing that don’t use BSL.

Take your time when talking and make sure it is easy for them to lip-read you.

In busy meeting scenarios, allow the deaf employee time afterwards to proecss the information and follow up with the invidiual to ensure that they fully understood what was discussed in the meeting.

5.3 Supporting a deaf friend/family member

Activity 7 Ian and his family at home

Ian, like many deaf people, always finds it a challenge when he’s trying to convey how he feels about a matter that’s important to him to his parents. They just don’t quite get it. They know the basics of BSL and have even completed several courses. However, they don’t often seem to understand Ian’s emotions fully when he opens up to them.

Write down your thoughts on this scenario and what you could do to help if this was your friend/family member.

Discussion

Within the immediate family, it is highly beneficial if parents are proficient in sign language. For friends, siblings and members of the wider family it would be useful to be able to do some of the basics. However, it is a big challenge!

During family time, try to speak one at a time: that way everyone feels included and you’re not intentionally excluding your loved ones. For those family members that may wear a hearing device such as a hearing aid, there are quite a few hearing aid drop-in clinics where a battery or tube can be easily replaced.

Encouraging deaf family members to write some of their thoughts down can be really helpful too, especially when they would like to explain a difficult situation or complex set of emotions. Putting pen to paper can be a good starting point but always try, where possible, to follow it up with face-to-face interaction. There can be no substitute for this interaction.

Being able to communicate and understand with our family and friends is something that we take for granted. These communication methods will hopefully help a deaf or hard of hearing person feel included and, more importantly, listened to and loved.

6 Summary test

a.

The correct answer is a.

a.

Tinnitus

b.

Accute deafness

c.

Profound deafness

The correct answer is b.

a.

1921

b.

2010

c.

1967

d.

1979

The correct answer is d.

a.

Subject, verb, object

b.

Verb, subject, object

c.

Object, verb, subject

The correct answer is a.

Match up the sections of the ear.

Using the following two lists, match each numbered item with the correct letter.

Auricle

Incus

Cochlea

a.Inner Ear

b.Inner Ear

c.Middle Ear

- 1 = a

- 2 = c

- 3 = b

7 Conclusion

Congratulations, you’ve completed the course in Deaf awareness for education.

Hopefully you now have an understanding of the different types of hearing loss, and strategies to use to ensure deaf and hard of hearing students can be included in their everyday learning, as well as how to be more inclusive in everyday scenarios.

Thank you for taking the time to complete this course and taking a first step to removing the communication barrier.

If you are interested in learning more about deafness and hearing loss you might find it useful to read: A Self-Guide Book on Deafness, Hearing Loss and Tinnitus.

8 About the author

J’enna Flynn is an experienced signer, a published author and Specialist Support Professional Tutor (SSPT). Having fallen in love with the language at the age of 16, J’enna embarked on her signing journey to one day become an interpreter. J’enna graduated from the University of Wolverhampton with a BA Hons in Deaf Studies and Linguistics and then went on to become a BSL level 6 signer, gaining qualifications with PTLLS and TEFL.

J’enna has worked within the Deaf community for numerous years, not just as a signer but also as a Specialist Support Professional Tutor, supporting deaf and hard of hearing students access their education. J’enna is experienced in signing within the education sector and signs for many deaf clients within the workplace via Access to Work.

Should you require any support from J’enna, please contact her at jflynnbsl@gmail.com.

References

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements

This free course was written by J’enna Flynn and was first published in September 2020.

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence .

The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this free course.

Video

Course introduction video by Jamie Lakes.

Images

Figure 2: Image by Taylor Wilcox from Unsplash

Figure 4: Image by Gordon Johnson from Pixabay

Figure 6: Image by Bang Oland from Dreamstime

Figure 7: Image by adriaticfoto from Shutterstock