Overview of genebank processes

The contribution your genebank makes to the successful conservation of crop genetic resources is key to addressing global challenges to food security. Seed storage is an efficient and cost-effective way of conserving plant germplasm ex situ. Over the past half century, the science of seed conservation has developed a well-documented sequence of processes to achieve this.

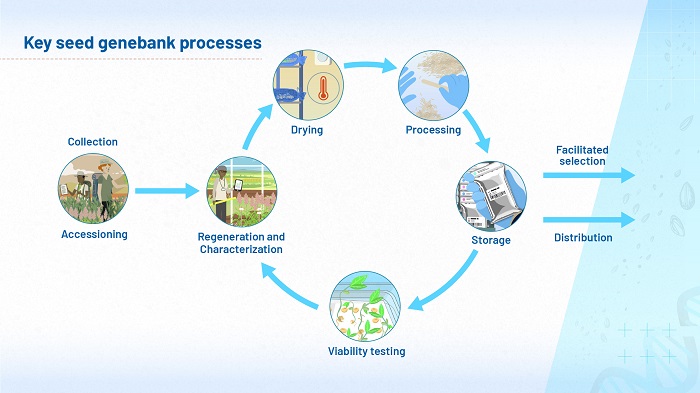

Figure 1 (above) summarises ‘business as usual’ at a typical seed genebank. When a sample first arrives at the genebank, the genebank manager decides whether or not it should be added to the genebank’s collection as an accession. The sample is assessed based on origin, name and the uniqueness of its traits, as well as whether it has been provided according to relevant international and national laws. If it has been sent from a different country, it may be necessary to grow the original sample under quarantine conditions and check for the presence of disease.

The sample is then multiplied (by growing the seeds and harvesting from the resulting plants) to produce a sufficient number of seeds for storage. Then begins an on-going cycle of drying, cleaning, packing, storage, viability testing and regeneration. The idea is to ensure that the seeds remain viable, and that there are always enough of them in stock to respond to demand from users. Characterization allows scientists to check the unique features of the germplasm in their care, while phytosanitary testing is carried out to eliminate pests.

Many genebanks have medium-term and long-term storage facilities, and all genebanks are encouraged to carry out safety duplication. The active collection (medium-term) is stored at around 5°C, while the base collection (long-term) is usually stored at around -18°C.

The detail varies between seed genebanks, genebanks using in vitro methods, and genebanks conserving crops that show vegetative propagation. However, all genebanks aspire to a cyclical sequence of processing, storage, safety duplication and recovery of vigor, leading to a steady supply of viable germplasm.

Among the worst things that could happen to a genebank’s carefully curated samples is for seeds to perish in storage, due to inappropriate storage conditions. Underpinning the success of the entire conservation stage are two important attributes of seeds, longevity and viability. In this course you will learn about recent discoveries made by scientists working in genebanks: scientists like you. You will benefit from the experience of CGIAR genebanks, in their search for ways to improve the viability and longevity of seeds. After you have finished this course, you may even be able to make your own contribution to our knowledge about the science of seed quality.

Introduction