4.1 Assessing coughs or difficult breathing

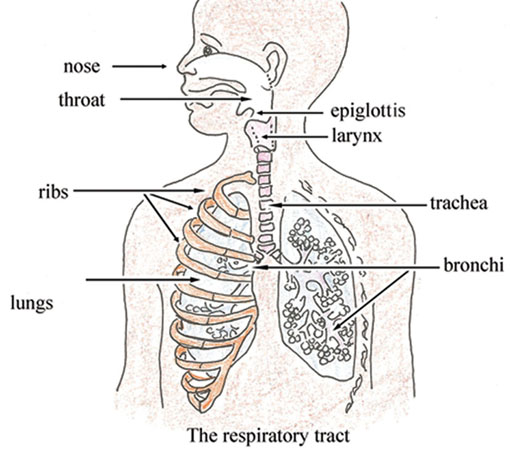

In order to assess coughs or difficult breathing, you need to know about the structure of the airways. Figure 4.1 shows the terms for the main structures that you need to know. You may already be familiar with some or even all of the terms.

You can see in Figure 4.1 that the airway (or respiratory tract) structures include the nose, throat, larynx, trachea and bronchi (the main air tubes inside the lungs). Coughs or difficult breathing may occur when there is an infection of the respiratory tract. These infections may be severe respiratory tract infections such as pneumonia (acute) which require antibiotics for treatment, or they can be mild infections such as a cold, which can be treated by the family at home.

Health Extension Practitioners must be able to identify the few very sick children who have cough or difficult breathing, which need treatment with antibiotics. Fortunately, it is possible to identify almost all cases of pneumonia by checking for these two clinical signs: fast breathing and chest in-drawing. Stridor in a child (see the definition below) can also be a sign of pneumonia or another very severe disease.

For all sick children who come to your practice, ask the mother if the child has cough or difficult breathing.

You are now going to look at the steps involved in assessing and classifying children with cough or difficult breathing.

For all sick children whom you encounter in your practice, you should ask the mother or caregiver whether the child has cough or difficult breathing. You should then ask how long the child has had cough or difficult breathing.

Then you need to assess for the following:

Fast breathing: breathing rate per minute higher than normal for the age group.

Chest in-drawing: the lower chest wall (lower ribs) goes in when the child breathes in.

Stridor: a harsh noise which is made when the child breathes in.

Stridor is pronounced ‘stry-dore’.

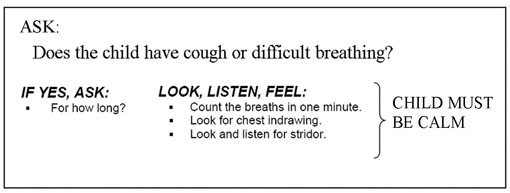

Box 4.1 below is taken from the IMNCI Assess and Classify chart booklet and summarises the steps you should take when assessing a child for a cough or difficult breathing.

Box 4.1 Assessing cough or difficult breathing

You are now going to look at each of these steps in more detail.

ASSESS whether the child has cough or any difficult breathing

Difficult breathing is any unusual pattern of breathing. Mothers describe this in different ways. They may say that their child’s breathing is ‘fast’ or ‘noisy’ or ‘interrupted.’

If the mother says the child does not have cough or difficult breathing, you should still look at the child yourself to see whether you think the child has either of these symptoms. If the child does not have cough or difficult breathing, you do not need to assess the child further for signs related to either of these symptoms. You should go on to ask about the next main symptom, which is diarrhoea (you will read about how to assess and classify diarrhoea in Study Session 5).

If the mother answers ‘Yes’ to your question about whether the child has cough or difficult breathing, you should ask her the next question.

ASK: how long has the child had cough or difficult breathing?

A child who has had cough or difficult breathing for more than 21 days has a chronic cough. This may be a sign of tuberculosis, asthma, whooping cough or another respiratory problem.

COUNT the number of breaths the child takes in one minute

Count the breathing rate as you would in a young infant. The cut-off for fast breathing depends on the child's age. Young infants usually breathe faster than older infants and young children.

| If the child is: | The child has fast breathing if you count: |

|---|---|

| 2 months up to 12 months | 50 breaths per minute or more |

| 12 months up to 5 years: | 40 breaths per minute or more |

You should note that the child who is exactly 12 months old has fast breathing if you count 40 breaths per minute or more.

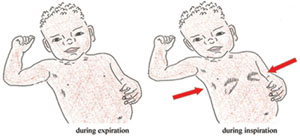

LOOK for chest in-drawing

You learned about chest in-drawing (also called subcostal redrawing or subcostal retraction) and how to examine a young infant for this sign, in Study Session 3 of this Module. In a child age two months up to five years, if chest in-drawing is clearly visible and present all the time during an examination, it is a sign of severe pneumonia or very severe disease (see Figure 4.2 which illustrates in-drawing). Unlike in the young infant, mild chest in-drawing is not normal in older infants and children.

LISTEN for stridor

Stridor happens when there is a swelling of the larynx, trachea or epiglottis (see Figure 4.1 to remind yourself where these structures are). This swelling interferes with air entering the lungs. It can be life-threatening when the swelling causes the child's airway to be blocked. A child who has stridor when calm has a dangerous condition.

Listen for stridor when the child breathes in. Put your ear near the child's mouth because stridor can be difficult to hear. A child who is not very ill may have stridor only when crying or upset. Be sure to listen for stridor when the child is calm.

What three signs in a sick child indicate the possibility of pneumonia or another very severe disease?

If you identify any general danger sign, fast breathing, or chest in-drawing, and if you hear a harsh noise from the child when calm and breathing in (stridor), the child is likely to have severe pneumonia or another very severe disease.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 4