2.2 Parasite, food webs and energy flows in aquatic ecosystems

The example just looked at is dramatic and, for many, increasingly familiar. It illustrates a broader point: that the influence of parasites on the population dynamics of their hosts is deeply embedded in ecosystems and directly impacts interspecific competition and the structure of food webs. A well-known land-based example is the introduction of the rinderpest virus in 1889: the disease killed the majority of the African Savannah grazing ungulates, thus starving and reducing the population of predatory carnivores. With no grazers left, the grass grew tall and increased the frequency of fire, reducing resources for tree-feeding species such as giraffes.

Similar situations have been documented for aquatic ecosystems, for which the influence of parasitism on food web structure and energy flow is vastly recognised. In all environments, and at all trophic levels, parasites and pathogens are increasingly being considered of equal importance with predators for ecosystem functioning, both in pristine and disturbed ecosystems.

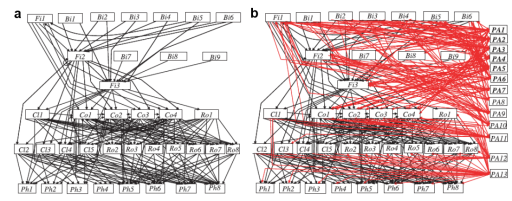

Figure 6 shows the complexity of ecosystem links. The thing to note is the significance of parasites: they typically account for the majority of total food web links and as such accelerate the recycling of organic matter.

2.1.4 Infection of Cochlodinium polykrikoides by Amoebophrya