Background (Simple harmonic motion)

Background

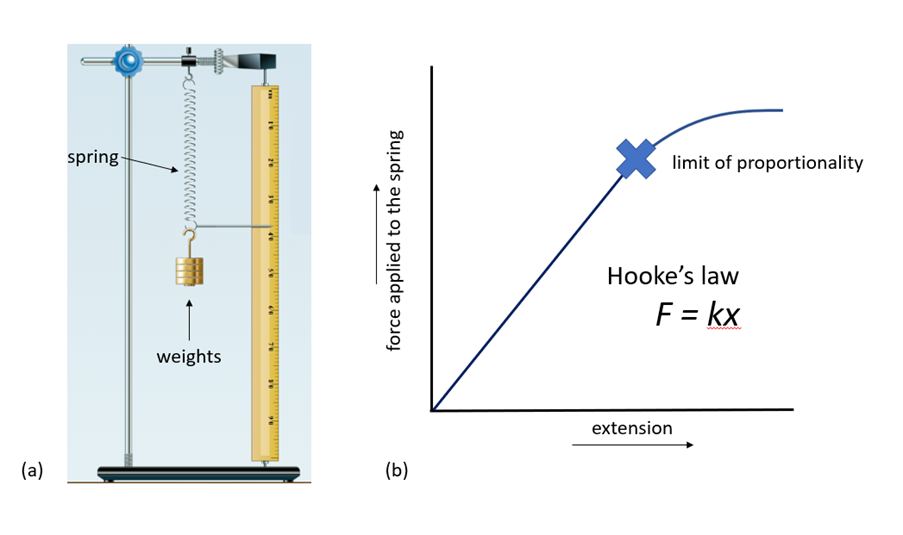

In a previous lesson ‘Determining a spring force constant’ you learnt that as force is applied to a spring, it will extend in a linear and proportional manner until it reaches its limit of proportionality or elastic limit. You also learnt that Hooke’s law can be used to calculate the force constant of a spring – a measure of a spring’s stiffness within the limit of proportionality.

Figure 1 (a) a spring mass system used to measure the extension of a spring when force is applied in the form of weights, (b) a graph showing the extension of a spring with increasing applied force. Hooke’s law is used to calculate the spring force constant (k), where F is the applied force and x the extension of the spring. Note: Hooke’s law only applies below the limit of proportionality when the extension of a spring is proportional to the applied force.

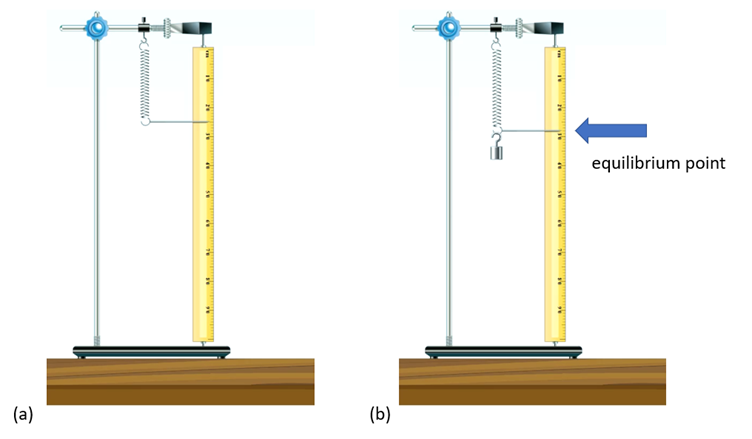

When a weight is added to a spring it will cause the spring to extend downwards to a new resting extension or equilibrium point, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 (a) a spring at rest. (b) the same spring as in (a) but now extended to a new resting position by the addition of a weight, this new position is called the equilibrium point indicated by the blue arrow.

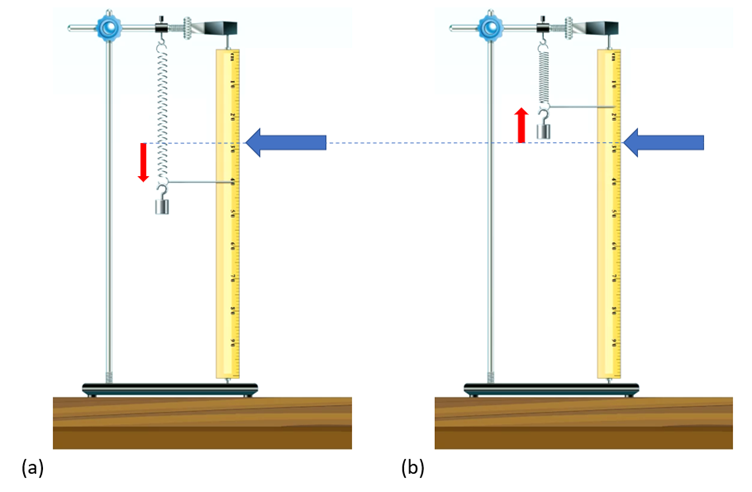

If the weight is pulled downwards (displaced) and then let go, the spring will start to oscillate around the equilibrium point (Figure 3).

Figure 3 (a) a weighted spring is pulled downwards (red arrow) away from its equilibrium point (indicated by the blue arrow and blue dashed line). (b) when the downward force is released, the spring will move upwards, passing through the equilibrium point and reaching a point where the upward motion ceases (red arrow).

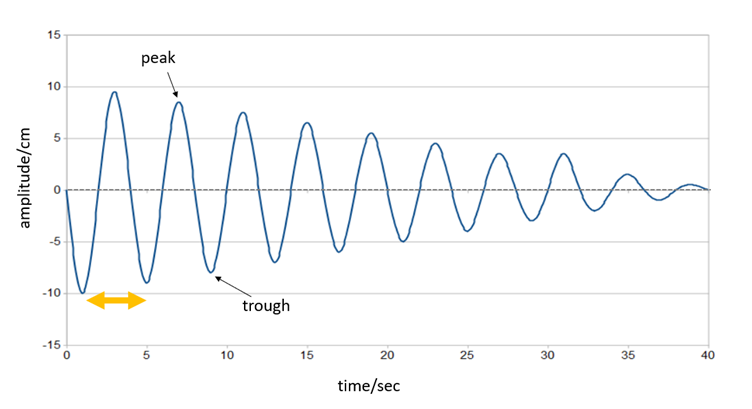

Figure 4 shows a plot of the motion of a weighted spring that was displaced by 10 cm and then released. As you can see, the weighted spring oscillates, moving up and down in a regular rhythm until it comes to rest – this type of oscillation is called simple harmonic motion. A defining feature of harmonic oscillation is that the rhythm is regular, that it is a series of repeated cycles occurring at a fixed frequency. The reason why a weighted spring oscillates is that the applied displacement initiates a complex interaction between kinetic energy and stored potential energy that sustains the oscillatory motion until it stops.

Figure 4 The oscillatory motion of a weighted spring resembles a series of waves with peaks and troughs as it moves up and down around its equilibrium point (indicated by the dashed line). A full cycle (yellow double-headed arrow) is the movement of the spring as it starts from a starting point, for example the trough, moves upwards to the peak and then returns to its starting point. In the example shown, the cycle takes about four seconds.

The example of a harmonic oscillation shown in Figure 4 has a slow cycle (taking about four seconds) and because a cycle is measured using units of time it is called the period (T). You will also notice that the oscillations do not continue indefinitely, they eventually stop – this is because of friction, both from the air and the microstructure of the spring itself.

|

If it takes an oscillating spring 5 ms to move from its equilibrium point to the peak of an oscillation, what is the period? |

The period of an oscillation can also be expressed as a frequency. The unit used for frequency is hertz (Hz). A frequency of 1 Hz is equal to a period of 1 second, or in other words, one cycle per second. An oscillating spring with a period of 500 ms will complete two cycles in 1 second and in this case the frequency is expressed as 2 Hz (two cycles per second).

|

If it takes an oscillating spring 5 ms to move from its equilibrium point to the peak of an oscillation, what is the period? |

In the practical activity you will explore the relationship between mass, the displacement of a spring and the period. You will also use the period and mass to measure the spring force constant.

Previous: Lesson objectives Next: Practical activity