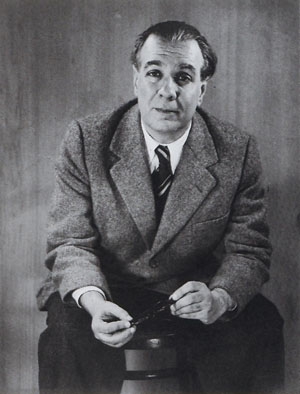

Jorge Luis Borges in 1951

Borges also had his own library - The Library of Babel - which he created as a project for an Argentine publisher:

Jorge Luis Borges in 1951

Borges also had his own library - The Library of Babel - which he created as a project for an Argentine publisher:

Although he disliked the bureaucratic boredom of library work, Borges was better suited than perhaps anyone for a curatorial role. Given this reputation, Borges was asked more than once to select his favorite novels and stories for published anthologies. One such multi-volume project, titled Personal Library, saw Borgesselecting 74 titles for an Argentine publisher between 1985 and his death in 1988. In another, Borges chose “a list of authors,” Monroe writes, “whose works were selected to fill 33 volumes in The Library of Babel, a 1979 Spanish language anthology of fantastic literature edited by Borges, named after his earlier story by the same name.”

Borges' fictional Library of Babel was slightly different than a mere collection of well-chosen books:

The Library of Babel is different from any other library. In it, we find all books that have been written and those that will be written, those that make sense and completely absurd ones, works that group meaningless sequences of letters compiled into random arrangements with no purpose whatsoever. Everything that has been and will be thought can be found in a forsaken corner of the endless library.

Borges clearly had in mind a geometrical rendition of the cosmos for his library: “The Universe (that some call the Library) is composed of an undefined, maybe infinite number of hexagonal galleries.”

Read at NPR: Borges, The Universe And The Infinite Library

His fans hnoured Borges by making this infinite library a reality, of sorts:

Jonathan Basile, who lives in Brooklyn, New York, has spent six months creating a digital version of The Library of Babel – which contained all possible books with “all possible combinations of letters”.

Mr Basile described his online library as having "more books than the universe has atoms". He said: “If completed... it would contain every book that ever has been written, and every book that ever could be – including every play, every song, every scientific paper, every legal decision, every constitution, every piece of scripture and so on."

Read at The Independent: Jorge Luis Borges fan brings his infinite library to life online

Did Borges really understand the science that lay at the heart of his work? Marcus DuSautoy considered this question for BBC Radio 4:

Listen at iPlayer Radio: Great Lives - Marcus du Sautoy on Jorge Luis Borges

The Economist has dipped into its archive and produced a profile from 2004:

The writer's passionate anti-Peronism led him towards the contradictory position of embracing, briefly, the murderous military dictatorship of 1976-83. It was, he said, a “necessary evil”. Despite this political naivety, Borges had a nobler vision than many of his narrow-minded critics. An Anglophile, he insisted that he was part of a universal culture and refused to be pigeon-holed as an Argentine writer, though he was that, too, of course. As a young man, he idealised the Buenos Aires underworld—its knife fighters provided him with a recurring theme. Yet in a conscious snub to Argentine nationalism, he chose to die in Geneva.

Read at The Economist: Sightless seer of Buenos Aires

Borges film reviewing career ended by the time he was 55, when his degenerative eye disease left him totally blind. Before that time, though, he'd reviewed many movies which had gone on to become touchstones of cinema. Films like King Kong:

A monkey, forty feet tall (some fans say forty-five) may have obvious charms, bust those charms have not convinced this viewer. King Kong is no full-blooded ape but rather a rusty, desiccated machine whose movements are downright clumsy. His only virtue, his height, did not impress the cinematographer, who persisted in photographing him form above rather than from below—the wrong angle, as it neutralizes and even diminishes the ape’s overpraised stature. He is actually hunchbacked and bowlegged, attributes that serve only to reduce him in the spectator’s eye. To keep him from looking the least bit extraordinary, they make him do battle with far more unusual monsters and have him reside in caves of false cathedral splendor, where his infamous size again loses all proportion. But what finally demolishes both the gorilla and the film is his romantic love—or lust—for Fay Wray.

Read at Flicker: Jorge Luis Borges On Film

Interrelevant has Borges' review of Citizen Kane:

A kind of metaphysical detective story, its subject (both psychological and allegorical) is the investigation of a man’s inner self, through the works he has wrought, the words he has spoken, the many lives he has ruined. The same technique was used by Joseph Conrad in Chance (1914) and in that beautiful film The Power and the Glory: a rhapsody of miscellaneous scenes without chronological order. Overwhelmingly, endlessly, Orson Welles shows fragments of the life of the man, Charles Foster kane, and invites us to combine them and to reconstruct him. Form of multiplicity and incongruity abound in the film: the first scenes record the treasures amassed by Kane; in one of the last, a poor woman, luxuriant and suffering, plays with an enormous jigsaw puzzle on the floor of a palace that is also a museum. At the end we realize that the fragments are not governed by any secret unity: the detested Charles Foster Kane is a simulacrum, a chaos of appearances. (A possible corollary, foreseen by David Hume, Ernst Mach, and our own Macedonio Fernandez: no man knows who he is, no man is anyone.)

Read at Interrelevant: Borges Reviews ‘Citizen Kane’

For an full overview of his life and work, The New York Times obituary published on his death in 1986 is a good place to start:

For Mr. Borges, the short story - a literary form ''whose indispensable elements are economy and a clearly stated beginning, middle and end'' -was the most compelling form. Once he wrote: ''In the course of a lifetime devoted chiefly to books, I have read but few novels and, in most cases, only a sense of duty has enabled me to find my way to their last page. I have always been a reader and rereader of short stories.''

Read at the New York Times: Jorge Luis Borges, A Master of Fantasy and Fable, is Dead

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews