What was the Empire Marketing Board?

The Empire Marketing Board (EMB) was founded in May 1926, as a small government body with committees for research, marketing and publicity. Much of its effort (up to 65% of its yearly expenditure) went into encouraging research and analysis, including into how to improve the quality, storage and distribution of British and colonial produce.

It was set up with the Secretary of State for the Colonies (then Leopold Amery) as its Chairman, with a civil servant (Stephen Tallents, Sir Stephen from 1932) as its Secretary.

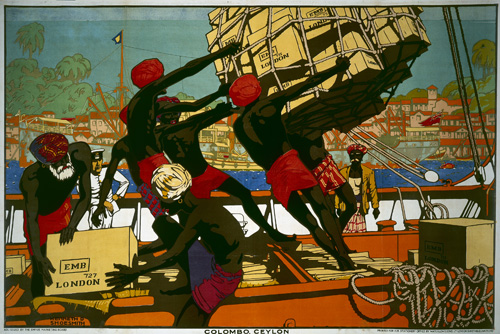

But it also employed people from the media, advertising and commercial world more generally, as well as giving commissions to some of the most talented poster artists of the day. The 1928 poster ‘Colombo, Ceylon’, for instance, was made for the ‘Our Trade with the East’ series by Kenneth D. Shoesmith. Shoesmith was already famous for his pictures of ocean ships and liners, and for depicting them in their exotic if not romanticised destinations.

'Colombo Ceylon', by Kenneth D. Shoesmith; 60 x 40 ins, displayed December 1928; Waterlow and Sons Ltd, London; from the 'Our Trade with the East' series of posters; EMB ref AD1.

'Colombo Ceylon', by Kenneth D. Shoesmith; 60 x 40 ins, displayed December 1928; Waterlow and Sons Ltd, London; from the 'Our Trade with the East' series of posters; EMB ref AD1.

Look at the image above. What does peoples dress, posture, roles and general depiction suggest about race, class and hierarchy in empire?

The EMB nevertheless had a fairly small budget, which was further cut due to general austerity measures in the depression, with the organisation as a whole being disbanded in September 1933.

After its demise, the film collection it had built up at the Imperial Institute in London changed hands, but was still maintained there. Influential EMB personnel such as Sir Stephen Tallents also took their ideals and experience to new bodies, such as the General Post Office.

Why did a power that spanned a quarter of the globe need to persuade people to ‘Buy Empire’?

Despite other countries increasing tariffs on British exports, Britain had failed to establish ‘Empire Preference’. A commitment to fostering global free trade, entrenched since the 1840s, made that difficult. A 1923 imperial conference did suggest Britain should charge tariffs on imports while exempting Empire produce. But this might raise food prices, and the issue contributed to Conservative losses in 1923 elections.

When the Conservatives came to power in October 1924, therefore, they were acutely aware that Britain’s traditional commitment to free trade and its hunger for cheap food imports still made ‘Imperial Preference’ politically toxic. They were not yet willing to risk raising tariffs on non-Empire imports.

They also wanted to boost Empire sentiment and links more generally, at a time when jingoistic appeals had become less potent in the wake of grinding trench warfare. In addition, the notion of imperial control as trusteeship – rule that should be specifically for the benefit of the ruled – was growing, as was the electoral strength of a Labour Party that was generally more suspicious of imperialism.

The Conservative Government’s solution to these dilemmas was the EMB, in the hope that it could boost empire trade by raising the quality of British and colonial produce, and by influencing consumer behaviour.

The EMB’s marketing, meanwhile, marked a wider shift in emphasis: from empire as an arena for military prowess and the display of superior metropolitan character; towards Empire as an actively interacting economic and cultural community, and a way of enriching metropole and colonies alike.

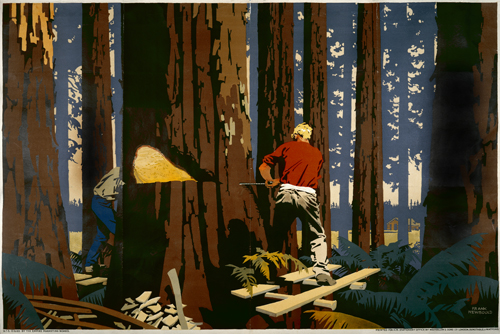

'Canadian Lumbermen', by Frank Newbould, from the 'The Empire is Still Building' series of posters; 60 x 40 ins; displayed September-October 1930; (TNA) CO956/225

'Canadian Lumbermen', by Frank Newbould, from the 'The Empire is Still Building' series of posters; 60 x 40 ins; displayed September-October 1930; (TNA) CO956/225

What killed the Empire Marketing Board?

The board’s demise in 1933 was partly due partly due to severe government cuts, which had already eroded its budget. But it was also due to Imperial Preference becoming politically viable. The World Depression that developed after 1929 held down commodity prices, reduced world trade generally, and saw tariffs and barriers against British and Empire exports rise. The 1932 Empire Economic Conference in Ottawa saw Britain and the Dominions agree to implement Imperial Preference, and by 1 October 1933 the EMB was gone.

Did the Empire Marketing Board succeed?

Empire’s share of Britain’s imports increased from 27% in 1930 to 39% in 1935. But that was also driven by increasing protectionism in international trade, and by the 1932 Ottawa preferential tariffs, which put higher tariffs on non-empire than on empire goods. While de Bromhead et al (2019 ) have argued that the EMB underlay two-thirds of this change, Higgins and Varian (2019, 2021) argue that ingrained consumer preferences (for instance for Danish over empire butter, and Argentinian over Australian beef), and consumer price sensitivity, amongst other things, meant the impact was far less. Examining the data for trade shifts after key product campaigns, they conclude changes attributable directly to specific campaigns were marginal. It seems likely, however, that the EMB had a more general effect on consumer awareness, and on general perceptions of empire.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews