Portrait of Claire ClairmontHowever, Mary Shelley left out one further person who was present on that night at the Villa Diodati – her stepsister, and Byron’s lover, Claire Clairmont. The erasure would have been made with Claire’s blessing. In 1831, when Mary wrote about this scene of origin for her novel, Claire was struggling to make a living as a governess in the polite drawing rooms of Europe, and the last thing she needed was to remind potential employers of her scandalous past. Claire also managed to prevent mentions of herself in other biographies and memoirs published at the time. She was happy to be forgotten.

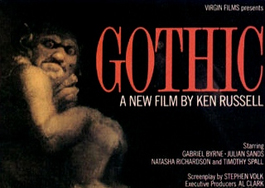

Portrait of Claire ClairmontHowever, Mary Shelley left out one further person who was present on that night at the Villa Diodati – her stepsister, and Byron’s lover, Claire Clairmont. The erasure would have been made with Claire’s blessing. In 1831, when Mary wrote about this scene of origin for her novel, Claire was struggling to make a living as a governess in the polite drawing rooms of Europe, and the last thing she needed was to remind potential employers of her scandalous past. Claire also managed to prevent mentions of herself in other biographies and memoirs published at the time. She was happy to be forgotten.In the two hundred years since, she has been reinstated in the many retellings of that night, in both fact and fiction. However, she doesn’t emerge well from many of them, being depicted as a talentless hanger-on or spurned lover. She is often a foil to the poised and talented Mary, or presented as Byron’s mistake. At first glance, her depiction in Ken Russell’s 1986 film Gothic (released by the BFI on Blu-ray) is of a piece with these portraits, if not the apotheosis of them.

Gothic takes place over one night, with the five of the original party staging the famous ghost story competition, as well as a séance to ‘conjure up their darkest fears’. These events form the pivotal points of the narrative. As each of the group in turn confronts their demons in a house that may or may not actually be haunted, hysteria builds. Are the demons real? Conjured up by their séance? Or are they hallucinations produced by too much laudanum? It is a classic Ken Russell concoction, an orgiastic riot of sex, drugs and horror that every gossipmonger of the time, and probably since, has dreamed of.

Myriam Cyr as Claire is wild and irreverent, and counterpointed with Natasha Richardson’s composed and gracious Mary Shelley. Lord Byron is played by a glowering Gabriel Byrne, while Percy Shelley is an exuberant adventurer of the spirit, as depicted by the late Julian Sands. A young Timothy Spall as a frankly unhinged John Polidori completes the quintet.

An interview with the actress Myriam Cyr, in which she talks about playing the role of Claire Clairmont in Gothic:

As with any Russell film, an already dramatic scene is heightened further by the performances and mise-en-scène. Cyr’s curly hair is teased into a huge halo around her face, and her naturally large eyes are used to their full advantage, giving a feral touch to her portrait of youthful high spirits. She is more sexually assertive than Mary and delights in Byron’s demonic transgressiveness. She scampers, giggles, and runs everywhere. In the elegant setting, compared to the composure of the other characters, she seems out of keeping. All in all she is loud, inappropriate, sexualised – characteristics of many female characters in popular culture dismissed as ‘unlikeable’. But rather than dismiss her, instead – as a number of feminist commentators have been doing recently – it’s worth taking a closer look at this portrait.

She enjoys a volatile, not to say masochistic relationship with Byron. We see her push boundaries with him, referring at one point to his club foot as a ‘cloven hoof’ which sends him into a violent rage. This provokes fear in her, but also pleasure. Although Byron is the dark leader of the revels, Claire is his partner in crime. And like him, she can also be cruel: taunting Polidori, running shrieking amongst the quietly labouring servants, saying of a child in one of the ghost stories they read that ‘they should have butchered the little brat.’

In many visual cues in the film she is also made physically repellent, despite Cyr’s attractiveness: she froths at the mouth during the séance, Shelley has a vision of her with eyes in her nipples, and in a typical moment of Russellian Grand Guignol, Byron bullies her at dinner by squeezing her cheeks viciously, forcing the spaghetti she’s eating to pour grotesquely from her mouth in close-up. Worse still, she doesn’t appear to care about any of this. She is resilient, even irrepressible in the face of Byron’s efforts to cow her.

The real Claire outlived all her companions in that 1816 summer by several decades, while her daughter by Byron, Allegra, died in an Italian convent at the age of five. She never married, always determined to retain what she called ‘my independency’. She travelled and worked across Europe during a revolutionary nineteenth century, including several years in Russia. This independence was always going to discomfit her contemporaries, so that she comes down to us distorted and judged for her attempt to live freely. In an age when we’re beginning to celebrate unlikeable female characters and anti-heroines, perhaps Claire Clairmont’s time has come.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews