Exploring the Pantheon further

The Hadrianic Pantheon is an example of Roman architecture at its most ingenious, partly because of the construction of the dome but also because of the ability to improvise, which Wilson Jones argues is what we see in the construction of the porch. Several hypotheses have been mooted to explain the aesthetic disharmony caused by the short columns which support the portico. The columns intended for the Pantheon may have been used by Hadrian in the Temple of Deified Trajan instead. Fifty-foot (15-metre) columns were difficult to quarry and transport, and even with exclusive control over the quarry from which the stone came (Mons Claudianus, in Egypt’s eastern desert) the emperor might not have been able to acquire the necessary components for both the Pantheon and the Temple of Deified Trajan. Time may also have been a factor. With Hadrian spending so little time in Rome, there were small windows of opportunity in which to complete – and celebrate the opening of – new public buildings (see also Wilson Jones, 2013, pp. 44–5).

The Pantheon is one of the few monuments to survive from the Hadrianic period, despite others in the vicinity having also been restored by him (SHA, Hadrian 19). What is unusual is that rather than replacing the dedicatory inscription with one which named him, Hadrian kept (or more likely recreated) the Agrippan inscription, reminding the populace of the original dedicator. At first this gives the impression that Hadrian was being modest, as he was not promoting himself. Contrast this with the second inscription on the façade, which commemorates the restoration of the Pantheon by Septimius Severus and Caracalla in 202 CE (CIL 6. 896). However, by reminding people of the Pantheon’s Augustan origins Hadrian was subtly associating himself with the first emperor. This helped him legitimise his position as ruler by suggesting that he was part of the natural succession of (deified) emperors. It is worth noting that Domitian had restored the Pantheon following a fire in 80 CE (Dio Cassius 66.24.2), but Hadrian chose to name the original dedicator of the temple, Agrippa, rather than linking himself with an unpopular emperor. In addition, the unique architecture of the Pantheon, with its vast dome, was a more subtle way for Hadrian to leave his signature on the building than an inscription might have been – and it would have been more easily ‘read’ by a largely illiterate population.

The Pantheon was embellished with a wealth of exotic materials. The porch was supported by columns of grey granite from Mons Claudianus and pink granite from Aswan (although most of the pink granite columns that survive today are seventeenth-century restorations). Those columns had bases and capitals of Pentelic (Greek) white marble, traces of which also remain on the exterior panelling. Yellow Numidian marble from Chemtou in Tunisia was used for the steps. Much of the interior decoration has been restored, but traces remain of Numidian yellow, as well as Phrygian purple and Lucullan black, both from different parts of Turkey, and roundels of red porphyry from Egypt.

The granite columns intended for use in the Pantheon may have been appropriated by Hadrian for the Temple of Deified Trajan. Coming from Mons Claudianus, these grey granite columns represented the southernmost frontier of Rome’s vast empire. Egypt had been an imperial province since its annexation by Augustus following the defeat of Antony and Cleopatra at Actium in 31 BCE. Consequently, the Egyptian granite columns, which no one but the emperor was entitled to use, also represented the far-reaching power of the emperor.

The Pantheon was a showcase of imperial power and the extent of the empire. In Hadrian’s case the Pantheon, and his other building projects, reflected his penchant for bringing aspects of the empire into Rome. This is nowhere more apparent than in the architecture and sculpture of Hadrian’s villa at Tivoli, but the Temple of Venus and Rome, which we will look at a little later in this course, is another good example.

Next in this section you will study the written sources for the Pantheon, to see what they can tell us about its meaning and purpose. Remember that our main sources for the Hadrianic period, Dio Cassius and the SHA, were written much later and are not entirely reliable.

Activity 5

Read the following sources:

- Primary Source 1: SHA, Hadrian 19. For this activity just read from ‘Although he built countless buildings …’ to ‘… the names of their original builders’

- Primary Source 3: Dio Cassius 53, 27.1–4.

What do the sources tell us about the meaning and purpose of the Pantheon? What was it used for? Did its meaning and purpose change in its different phases?

Discussion

The extract from the SHA confirms that Hadrian restored the Pantheon and other Agrippan monuments in the Campus Martius, and notes that he ‘dedicated all of them in the names of their original builders’ (SHA, Hadrian, 19.11). This corresponds to the evidence we have of the Agrippan inscription on the porch, as you saw in Activity 4 – M(arcus) AGRIPPA L(ucius) F(ilius) COS TERTIUM FECIT: ‘Marcus Agrippa, son of Lucius, three times consul, made this’. But the SHA tells us nothing about the meaning or purpose, and for that we must turn to Dio Cassius.

However, Dio Cassius seems unsure of the meaning of the Pantheon, though he does say the building was decorated with statues of Rome’s ‘many gods’ (53.27.2). He does not specifically describe the Pantheon as a temple. His account is also somewhat anachronistic, as he refers to Agrippa’s building projects in the Campus Martius, but goes on to describe the dome of the Hadrianic Pantheon (‘because of its vaulted roof, it resembles the heavens’: 53.27.2). In other words, his opinion of the meaning of the building is based on the structure he visited in his lifetime, rather than the original Agrippan building. This may lead us to question the reliability of his interpretation. The rest of Dio Cassius’ account suggests that Agrippa’s Pantheon was intended as a temple for worship of the emperor, but that Augustus balked at this. Nevertheless, statues of his divine ancestors, Venus, Mars and ‘the former Caesar’ (Divus Iulius), were placed in the Pantheon, along with statues of Augustus and Agrippa in the ‘ante-room’ – probably the porch (53.27.3). This collection of statues is not dissimilar to that found in Augustus’ Forum. An association with the imperial cult is perhaps corroborated by a later inscription (CIL 6. 2041) which reports that the Arval Brethren, who made regular vows for the well-being of Rome and the imperial family, met in the Pantheon in 59 CE.

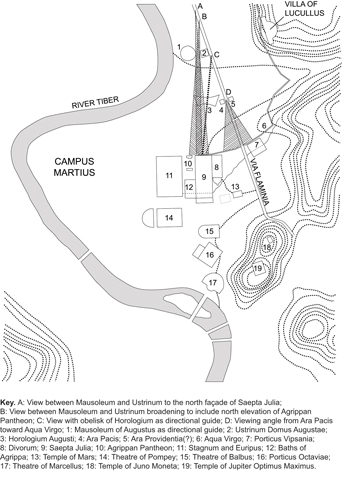

Ultimately, while we know little about the design and function of the Agrippan Pantheon, it is clear that it was an integral part of Augustus’ appropriation of the Campus Martius. Figure 12 shows that there was a direct line of sight from the entrance of Agrippa’s Pantheon to Augustus’ mausoleum (which you’ll study in Section 3). The Campus Martius was stamped with Augustus’ authority and legacy, much of which harked back to the myths of Rome’s foundation. In rebuilding the Pantheon, and keeping its original inscription, Hadrian wove himself into the Augustan narrative, although by then the line of intervisibility had been blocked by later buildings. It is perhaps unsurprising, though, that we find Hadrian’s mausoleum in the vicinity of both monuments.

Dio Cassius describes Hadrian’s use of the Pantheon, with an emphasis on public business rather than religious ritual:

He transacted with the aid of the senate all the important and most urgent business and he held court with the assistance of the foremost men, now in the palace, now in the Forum or the Pantheon or various other places, always being seated on a tribunal, so that whatever was done was made public.

This has much in common with the functions of the Imperial Fora, where divinely sanctioned public business took precedence. Both the Pantheon and the temples of the Imperial Fora seem to have represented the legitimacy of imperial rule, as the gods watched over the multifarious aspects of government. They were also arenas in which the emperor could remind Rome’s populace of the extent of the empire, and his personal control of it.

Imperial Rome, and Hadrianic Rome in particular, was a place that was embellished and influenced by the riches of empire. The materials used in the construction and decoration of the Pantheon show that Rome and the empire were integrated rather than separated, but they also acted as reminders of the power and wealth of the emperor. The following sections continue to explore these themes.