In the mid AD 80s, after the Romans withdrew from their forward positions in what is now Scotland, they constructed a timber fort half way along their supply road running from sea to sea, between modern Newcastle and Carlisle. They called it Vindolanda, probably putting into Latin a native name for the place that meant ‘white meadows’ or something similar.

Over the next 320 years Vindolanda was almost continuously occupied by a variety of Roman army regiments and the attendant camp followers. A succession of short-lived timber forts was eventually replaced by stone successors, and archaeologists have now recognised the presence of at least ten different forts on the site.

Until Hadrian’s Wall was constructed in the AD 120s, Vindolanda was one of a small number of forts guarding the supply road known now as the Stanegate, and during Wall construction it probably served as a supply base for the legionary builders. When the Wall was commissioned, Vindolanda was maintained as a fort ‘on the frontier’, taking its place between Housesteads and Great Chesters.

Like most Roman fort sites, Vindolanda had been used as a source of building stones by local landowners from times immemorial, but it was remote enough from the main modern roads to escape the worst of the destruction. Limited excavation in the early nineteenth century revealed a number of magnificent stone altars, with inscriptions naming the garrison as the Fourth Cohort of Gauls, 500 strong and part-mounted, and in the 1930s more excavation showed that some of the stone buildings were well preserved.

The modern excavation campaign started in the late 1960s. It was on a small scale, and conducted only with the grudging approval of the landowner, the farmer Thomas Harding. But in 1970 the farm was purchased by a benevolent Roman enthusiast, Daphne Archibald, who gave the field in which the principal remains lay to a newly formed registered charity, The Vindolanda Trust. Following this if the funds could be acquired, it would be possible to excavate on a large scale, hopefully to examine the entire site. Fortunately, sufficient members of the public came to see the work in progress to meet most of the bills, and gradually the Trust was able to employ staff, create its own Museum and offer its visitors decent facilities.

When the Trust started its work in 1970 and appointed me to the post of Director of Excavations, I estimated that it might take 25 years to complete the examination of the site. Now, 36 years later, I know that it will take at least another 100 years to achieve the target. I now realise that Vindolanda was a much larger place than previously thought, and that multiple layers of occupation extend down to six metres in places – and in many parts those earliest layers are preserved in anaerobic conditions.

Such conditions are very rare in Britain, but they can provide the most vivid picture of life on the Roman frontier, for virtually everything that was left behind by the occupants survives in good condition, including all the normally perishable items like leather goods, textiles, wooden objects, flora and fauna – and their waste paper.

As far as we know, Vindolanda was never more than a normal garrison fort on the northern frontier, with the camp followers – wives, children, merchants, slaves, and so on – living outside the fort walls. Unlike most Wall forts, however, it had been in existence for some 40 years before Hadrian’s Wall was constructed, and therefore the remains were more extensive. But Vindolanda’s anaerobic anaerobic layers were found to include quantities of ink-written documents – private and official correspondence, stores lists, military orders, quotations from the Classics, and even drawings. The collection forms the earliest written archive in British history, and it has had a dramatic impact on our knowledge of Roman army life on the northern frontier.

There is only so much information that can be gained from a normal archaeological investigation of even the best preserved of remains, although for Roman Britain there has always been the chance of finding a meaningful inscription – the record of a building’s construction, a religious dedication or a tombstone, that give names and refers to specific events.

But Vindolanda’s writing tablets provide brilliant shafts of light on aspects of daily life than would otherwise remain entirely unknown. The names of hundreds of individuals have appeared, ranging from senior commanding officers to private soldiers, from officers’ wives to personal slaves, and from the Governor of Britain’s groom to baths orderlies, brewers, pig keepers, pharmacists and clerks. We learn of problems with the weather, of the shortage of beer supplies, of the slang name for the British (Brittunculi, or wretched little Brits), of appeals for mercy by a man claiming his innocence, of dinner and birthday parties, of hunting expeditions and problems with the supplies of goods, due to poor road conditions. It all amounts to a positive feast of information.

Something like 2,000 different tablets have been found so far, but the bulk of them are no more than scraps from deliberately shredded documents. But the complete scripts are wonderful, as the two examples below show. But to read them you have to be able to decipher the Roman cursive script, which is handwriting rather than the fine capital letters found on stone inscriptions, and you have to know your Latin! Even so there are problems, for many of the writers were somewhat careless with their spelling and punctuation, and they had a nasty tendency to use slang words that do not appear in Classical dictionaries.

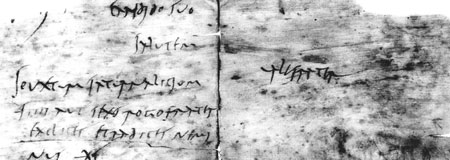

A letter between two slaves, in a fine script, but including a totally unknown word (the first word in line 3).

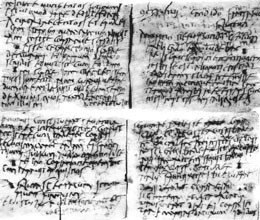

The letter of the left-handed Octavius to Candidus, reporting on the acquisition of considerable supplies and the urgent need for more money – and including the interesting statement that he would not send his mules down to Catterick to collect a wagon load of leather hides, because the roads were so bad.

The exceptional information in the writing tablets has to be combined with the archaeological information gained from 36 years of modern excavation. The finds include vast quantities of leather, ranging from army tents and footwear of every description to sling pouches and tool bags, and there are hundreds of textile fragments, wooden objects and even a hair-net and a wig woven from local moss. The architecture of both military and civilian buildings emphasises the impact of the Roman army on the traditional native structures, and the evidence for the extensive mining of iron, lead and coal reminds us that the local area experienced an industrial revolution when the army took control.

All this evidence has put flesh on the bare bones of that 300 and more years of Roman occupation. The soldiers and their dependents experienced a far higher standard of living than the natives were used to. They ate their meals off ceramic bowls imported from as far away as Southern Gaul, and they enjoyed Spanish olive oil, Portuguese fish sauces and pepper from India. Soldiers of all ranks, and their wives and slaves, maintained contacts with families and friends through written correspondence, and the sending of parcels was by no means uncommon.

The soldiers could use their pay – international currency - to acquire goods and services in the villages outside the fort walls, or they could purchase a wide variety of useful items from the regimental quartermasters. Obviously there were problems from time to time.

The tablets speak of thefts, of broken promises, of failures to answer letters, of sickness and even of army deserters, but there is nothing surprising in that. It appears to have been a pretty good life, far removed from Kipling’s view of ‘lonely Roman soldiers’.

After nearly 40 years of almost continuous excavation at Vindolanda, a fascinating and vivid picture has been presented. But to complete the examination of the site, another 100 years of work will be needed, and many new stories will emerge.

Find out more

Explore Hadrian's wall

Study history with The Open University

This article was originally published in 2006 as part of the OpenLearn Timewatch collection

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews