2.1 Assessing the evidence

We shall return to the idea of Alexandria’s universal library at the end of this free course – but before getting too caught up in these dizzying, seductive images, it’s important to assess the historical evidence carefully. Can we confidently state that this was a universal library? Indeed, can we confidently say anything about it? The library of Alexandria may symbolise the totality of the world’s knowledge – but we actually know very little with any certainty. Scholars have long argued that the Letter of Aristeas is fiction, a piece of Jewish propaganda aimed at Greek audiences, and there is no reason to believe its claims for the library’s universality, especially since it is riddled with other factual errors (such as wrongly naming Demetrius as the library’s first director). Indeed, many things that we think we know about the library prove to be mistaken, or uncertain at best, as the next activity will demonstrate.

Activity 2

Read Roger Bagnall, ‘Alexandria: library of dreams’ [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] (2002), from the start of the article up to ‘… hundreds of thousands of rolls’ (p. 356). You do not need to read the footnotes. As you read, pay careful attention to Bagnall’s account of the historical library, and the evidence he uses. What kind of picture of the library does he build up? Are you surprised by any of it?

Discussion

Bagnall’s article is an uncompromising and valuable account of the troubling gap between the popular image of the library of Alexandria and the limited reliable evidence that we actually possess. Each of the library’s key features is shown to rest on questionable historical foundations, not least the idea that it housed a ‘universal collection’; Bagnall argues that it is implausible to imagine a library housing the vast numbers of papyrus rolls (up to half a million) mentioned by many of the sources, since the figures could only be accurate if the library held a great many more ancient texts than we know about today – an unlikely scenario. He also doubts the often-repeated anecdotes about how the library acquired its collection – by ransacking passing ships, for example – and the assumption that the poet and scholar Callimachus could have catalogued the holdings of an entire library, especially a universal one. Even the founding of the library is uncertain, suggests Bagnall: impossible to attribute confidently to either of the first two Ptolemies.

You might also have noticed how the literary and archaeological records – or, rather, the lack of them – work together in Bagnall’s account. We might be able to say more about the library if the sketchy and unreliable ancient texts could be supplemented by useful archaeological evidence, but there is very little to go on – as Bagnall shows, the so-called granite papyrus containers are unlikely to have been used for this purpose.

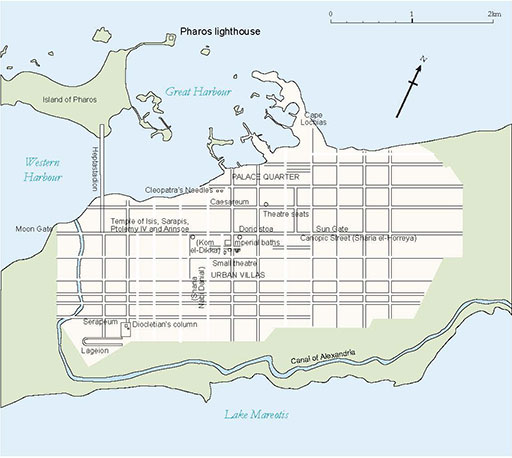

You might also have noticed how the literary and archaeological records – or rather, the lack of them – work together in Bagnall’s account. We might be able to say more about the library if the sketchy and unreliable ancient texts could be supplemented by useful archaeological evidence, but there is very little to go on – as Bagnall shows, the so-called granite papyrus containers are unlikely to have been used for this purpose. In a 2008 article Jean-Yves Empereur, the leader of excavations in Alexandria, explained why archaeological evidence for the library is in short supply. We know that the library was part of Alexandria’s Palace Quarter – which the map in Figure 1 shows as adjacent to the harbour – but seismic activity over the centuries has left this area of the city underwater, and the extent of the modern city also impedes access to its ancient remains. Moreover, if the library were to be found, suggests Empereur, would we even recognise it as such? Papyri would not have survived in Alexandria’s humid conditions (unlike the arid desert which preserved the Oxyrhynchus rolls), and the buildings would likely have consisted of simple stoas and other large spaces, making them possibly indistinguishable from other large buildings. Perhaps an inscription would give a key to the building’s identity, but interpreting inscriptions is itself rarely straightforward. Although the Egyptian authorities have occasionally trumpeted the discovery of so-called lecture halls, other archaeologists are sceptical.

You can read one such report from 2004, David Whitehouse: ‘Library of Alexandria discovered’, via the BBC News website.