1.2 The Second Sex, the 1960s and the feminist revolution

Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex became a crucial work for the feminist movement that developed from the 1960s onwards, although it was first published in 1949. Beauvoir was not only aware of the delay of its impact, but also regarded it as consistent with the inevitable obstacles that women encounter in understanding their own situation. In fact, she herself had not grasped the social condition of women, incorrectly projecting her own lucky situation as a financially independent, respected and successful intellectual, onto other women. In an interview with an American magazine in the early 1970s, Beauvoir said that only when writing The Second Sex had she ‘understood that the vast majority of women simply did not have the choices that [she] had had, that women are, in fact, defined and treated as a second sex by a male-oriented society’ (Beauvoir, 1976).

If the ‘vast majority of women’, as Beauvoir thinks, are oppressed everywhere, why do they often accept their situation? She thinks that women, like all ‘economically and politically dominated peoples anywhere’ first have to realise that they are in a disadvantaged and unfair position, and then they have to think it possible to change it. She also explains the reasons why it is not a matter of course that women are united in their struggle:

… those [women] who have the most to lose from taking a stand, that is, women like me who have carved out a successful sinecure or career, have to be willing to risk insecurity – be it merely ridicule – in order to gain self-respect. And they have to understand that those of their sisters who are most exploited will be the last to join them. A worker’s wife, for example, is least free to join the movement. She knows that her husband is more exploited than most feminist leaders and that he depends on her role as the housewife-mother to survive himself. Anyway, for all these reasons, women did not move.

The last sentence of the quotation, ‘…for all these reasons, women did not move’, refers to the time when The Second Sex was published. Although she had written a seminal feminist book, there was no feminist movement to join. Then, as she put it, ‘came 1968, and everything changed’. She continued:

[Women] became activists. They joined the marches, the demonstrations, the campaigns, the underground groups, the militant left. They fought, as much as any man, for a nonexploiting, nonalienating future. But what happened? In the groups or organizations they joined, they discovered that they were just as much a second sex as in the society they wanted to overturn. Here in France, and I dare say in America just as much, they found that the leaders were always the men.

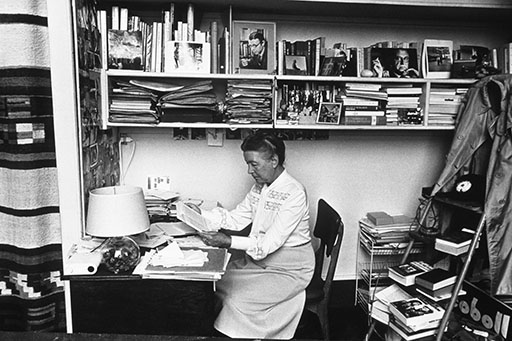

Beauvoir thought that it is important that women fight their own specific struggle. Here, though, you will study her philosophical writings, rather than following her on demonstrations and political activities – although in a sense, this cannot be separated from her philosophy. In several pictures in this course, you can see her in action!