The beginning

Elouise Chandler was born in what is now known as Guyana, South America on 28 December 1932. Her parents Erica and Samuel Chandler had ten children: five boys and five girls. Elouise was just six years old when her mother died aged only forty-two. She went to boarding school and studied at the Ursuline Convent school in Georgetown. In the holidays she would go home and spend weeks with her father moving up and down by barge between settlements on Guyana’s great Potaro river as her father carried out his engineering job. He was a dredgemaster for the industry mining for gold in the river.

In 1955, in Georgetown, British Guiana, Elouise Chandler married Mr Beresford Edwards. Little did they know then that it was the beginning of a powerful partnership that would have a lasting impact on the development of the West Indian community in Manchester.

At the time British Guiana was a UK colony and the Empire’s colonial people were British subjects with all the rights that this implied including free movement of people. In 1960, Beresford came to work in England and to study lithography. The following year Elouise came to join him bringing their young son. It was Beresford Junior’s third birthday when their ship docked at Plymouth. They then had a train journey to London. Elouise remembers it vividly:

It was June when I arrived and it was freezing cold. I remember the panic I felt ... it was all so different ... My son was three years old the day he landed. The poor kid, he was crying, he wanted to go back home.

The family lived in shared rental accommodation in several places in Moss Side, Manchester, until they finally owned their own home at 78 Platt Street. This was a real achievement. The anticipated warm welcome to the Mother Country had not materialised. Hostility towards the growing West Indian community was widespread. Rental accommodation was hard to find. The notorious “No Blacks, No Irish, No Dogs” signs in windows were all too common. Getting a mortgage was impossible. The West Indian community responded with “Pardner”. This was a system of communal saving based on trust. A group would join together to pool their regular savings. The money was kept by a trusted “banker” and the members took it in turn to have access to the lump sum. This enabled many families to put together the down payment on a house.

As Elouise’s husband, Beresford described it:

I used to throw what is called ‘pardner’ with some Grenadian people I know called Henry who used to live in Talbot Street. They used to work in the same factory as me. They assisted me by what you would call an early hand, you know, and I was able to send the passage home to pay for my wife and eldest son. Then on the next pardner round, I bought a house.

The West Indian Organisations Coordinating Committee

The home of the Edwards family became a place where people from all parts of the West Indies who were experiencing similar problems could meet and share advice. Elouise and her husband, popularly known as Berry, became increasingly involved in community affairs. People from the different West Indian territories were beginning to organise themselves to deal with the shared experience of exclusion and prejudice. In 1964, the couple, along with Betty Luckham, were among the founding members of the WIOCC, the West Indian Organisations Coordinating Committee.

The group, which included six West Indian territories, has created a lasting legacy which can be seen in the West Indian Centre on Carmoor Road in Longsight and in many organisations connected with the African Caribbean community in Manchester. The WIOCC became a focus for West Indian settlers in Manchester to build a base from which they could work together to develop strategies for overcoming the barriers they met. It became an influential umbrella group which could represent their shared interests to official bodies such as the City Council. In the early days, it posted on its notice board a list of employers willing to hire African Caribbean people, landlords who would rent to them and solicitors offering legal advice at the centre.

These initiatives addressed the economic wellbeing of the community and later led to the successful campaign to establish the Cariocca Enterprise Parks. However, the WIOCC was also established with the broader aim of promoting the social and cultural life of its members. They had a strong emphasis on provision for young people – organising play schemes, skills training and a Saturday Supplementary school in response to concerns about the underachievement of West Indian children in school

The Family Advice Centre

Elouise worked for many years at the Manchester University refectory and then at the Hotel Piccadilly in Manchester city centre before joining the Family Advice Centre in Moss Side in 1975. She worked first as a neighbourhood social worker and later as a community development officer. By now firmly rooted in the community, she brought her knowledge of people’s lives, her empathy with their struggles and triumphs and her understanding of how the official systems worked. Through her inspiration and guidance, several different groups were formed. This enabled individuals to come together to share experiences and organise strategies for addressing the issues that concerned them most. Elouise continued in this influential role until her retirement in 1998.

As her friend and colleague of many years, Judy Barnor, put it: “Elouise would be the instigator. She had the vision; she saw the need, she sowed the seed and she brought together the appropriate people to carry it out.”

Black Women’s Mutual Aid

In the early 1980s, with a group of local women, Elouise established the Black Women’s Mutual Aid. This provided a forum for mothers to support each other in addressing issues concerning their children’s education. The group met on Sunday afternoons to share experiences. In response to concern about their children’s negative experiences at school, they organised a conference for parents to consider the issues. They were addressed by women’s speakers from campaigning organisations in Manchester, Liverpool and London.

The group’s philosophy was inspired by the principle of “Each one, teach one”. This sharing approach was based on the African American experience during enslavement. Denied access to education, the enslaved who had learned to read and write undertook to pass on those skills. So members of the women’s group would support each other by being available to accompany parents on school visits, parents’ evenings, pupil case conferences and to make representation to the City Council Education Department on various issues. Recognising the need to fill a cultural gap in their children’s education, the group established the annual Roots Festival.

The Roots Festival

The name of the annual celebration was influenced by the television series of Alex Haley’s book Roots, which told the story of the eighteenth-century African Kunta Kinte’s enslavement in American and its impact on his descendants. The festival took its motto from the words of Marcus Garvey, the political activist and orator who is one of Jamaica’s national heroes: “A people without knowledge of their past history, origin and culture is like a tree without roots”.

The first festival was held in 1977 at Ducie High School in Moss Side. Nurtured and developed by Elouise and her determined co-campaigners, it was held annually for 13 years. One of the motivations of the festival was concern about the gulf between schools and their local communities and the adverse effect this had on the aspirations and academic achievement of children of African Caribbean heritage. The festival programmes regularly quoted Amilcar Cabral, Guinean Pan-Africanist: “Our children are the flowers of our struggle and the principal reason for our fight.”

The event provided a platform for the community, particularly young people, to showcase their talents, to learn about African and Caribbean cultures, and to celebrate the achievements of Black people in the fields of science, education and enterprise. It aimed to create a setting where parents and teachers, children and local people could develop better mutual understanding through working creatively together.

The festival motivated St Margaret’s Primary School in Whalley Range to organise a project where pupils interviewed older Caribbean people about their lives before and after coming to Manchester. The Roots organisers were inspired by this and decided to develop the research further. This became the Roots Oral History Project resulting in recorded interviews with men and women of the Windrush generation. With the support of the African Caribbean Language Unit in 8411 Moss Side Community Education Centre, a selection of these were published in 1992 in a booklet called ‘Rude Awakening: African Caribbean Settlers in Manchester - an Account’.

Abasindi

The influence of OWAAD, the Organisation for Women of Asian and African Descent, 1978–82, led to the creation of a number of Black women’s organisations. The activist Olive Morris was one of the founding members. In Moss Side, the Manchester Black Women’s Cooperative was formed. It initially focused on employment training for young Black mothers, but its purpose grew to become a more radical space for women’s activism, political growth and cultural development. Reflecting this evolution, in 1980 the group became Abasindi, the Zulu word meaning ‘survivors’. Their work expanded to include a Saturday school and cultural activities directed at celebrating Black identity through dance, drumming, crafts and hair grooming. They learned from visiting artists and musicians from parts of the Caribbean and Africa. They travelled to attend and to perform at cultural festivals in West Africa and the Caribbean. Throughout their development, Elouise was a committed supporter and worked in close partnership with the group on many cultural events and political campaigns.

Years later, after her retirement, Elouise reflected:

I was asked to explain what the Abasindi Black Women’s Cooperative means to me. I am grateful for the opportunity to do so as I’m only just beginning to realise the depth of feelings I experienced when I look back and remember the women and the things that they accomplished. Some of these women have since passed away and some have returned to their homelands but I shall never forget the strength that emanated from each and every one of them. It was that strength and courage that enabled me to become the person I am today.

This observation is very revealing of Elouise’s personality: while working in the community she was herself receptive to growing, learning and gaining insights from the people she interacted with as she moved from initiative to initiative, from group to group.

She was a supporter and an inspiration behind many services and provisions for the wellbeing and development of the African Caribbean community in Manchester. They include the African and Caribbean Mental Health Services for people aged 16 and over, the Sickle Cell Centre and the Chrysalis Family Centre on the Alexandra Park Estate, to name a few. Julie Asumu, Chrysalis Centre Manager, described Elouise’s influence in this way:

She is a woman with a vision which she shares with those who are ready to support and improve the lives of others while pursuing issues that benefit the community. ... Her involvement and encouragement led to Moss Side being the cradle of community development in Manchester. She exchanged positive ideas about community development with the government of the day to bring progress to the Black community. She was a peacemaker and never allowed small-minded people to override the giant strides she took in community development among her people.

Better Affordable Housing

Elouise was also deeply involved in the campaign to provide better affordable housing in the multicultural neighbourhoods of Manchester. She is one of the founding members of the Arawak Walton Housing Association. Established in 1994, this organisation is the result of a merger between the Walton Housing Association which has its roots as far back as 1978 and Arawak Housing inspired by Louise Da-Cocodia and founded in 1987. Arawak Walton Housing is now the largest independent black and minority ethnic housing association in north-west England.

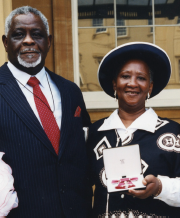

Recognition

Mama Edwards, as Elouise became affectionately known as, retired in 1998 and returned to Guyana. The organisations that she helped to build carry on her lifelong campaign for social justice. Pat Berkeley, who knew her through social events and community campaigns as well as through her work as a social worker, thinks of Elouise with love and respect:

“Where would many of us be today without the support of our elders. Mrs. Edwards set the standard for us to follow. She supported, guided, educated and encouraged us to be the citizens we are now. She lifted us all up ... to live in peace, security and harmony in the village she helped to build.”

In 1994, Elouise Edwards was awarded an MBE for her remarkable services to the Manchester community. Here was her response when the official letter arrived from the palace:

In addition to the MBE, Mama Edwards has received many other commendations for her services to the community, including an honorary MA from Manchester University and an honorary Chieftancy from the Nigerian community in Manchester. Throughout her extraordinary career, Mama Edwards was a full-time working wife, mother and later a devoted grandmother and great grandmother. These roles she held as among her greatest achievements. Echoing the Ashanti proverb, we can clearly see that Mama Edwards was a true warrior woman who fought with courage and not with anger.

After retiring to her beloved Guyana in September 2017, in January 2021 Elouise passed peacefully in her homeland. In the words of one of her favourite sayings, ‘A luta continua!’ – the struggle continues.

May she rest in peace.

Timeline for Elouise Edwards

1932 Elouise Chandler is born in Georgetown, British Guiana

1955 Elouise marries Beresford Edwards

1960 Beresford moves to England

1961 With 3-year-old Beresford Junior, Elouise joins Beresford in Manchester, England

1966 British Guiana becomes the independent republic of Guyana

1975 After years working in catering, Elouise joins the Family Advice Centre

1994 Elouise is awarded an MBE for her tireless service to her local community. Elouise also receives an honorary MA from Manchester University

1995 Elouise is honoured with a Chieftaincy by Manchester’s Nigerian community

1998 Elouise retires from the Family Advice Centre but continues to be an influential community activist

2017 Elouise retires to her beloved Guyana

2021 In January, Elouise dies in her homeland, aged 88 years

Web links and sources

Olive Morris: Google Doodle: Who was Olive Morris?

Rate and Review

Rate this video

Review this video

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Video reviews