Until the late eighteenth century, the predominant mode of landscape representation was the bird’s-eye view. This type of image offered the onlooker a high viewpoint outside the subject depicted within the frame of representation, whether a city, a coastline, or a pastoral scene. The aim to show as much as possible outweighed the concern for true perspective and straight sightlines. Robert Harbison captured the dynamic of the bird’s-eye view when he commented, of Wenceslaus Hollar’s 1648 “Long View” of London, “This is not exactly London as anyone experiences it, but London laid out neatly in the mind’s eye, where one can enumerate its features and remind oneself of many separate things at once”

Detail from Long View of London from Bankside, a panoramic etching made by Wenceslas Hollar in Antwerp, 1647. The image is six plates that join together, each consisting of drawings made from a single viewpoint, the tower of St Saviour in Southwark (now Southwark Cathedral) Select image for the full panorama

Detail from Long View of London from Bankside, a panoramic etching made by Wenceslas Hollar in Antwerp, 1647. The image is six plates that join together, each consisting of drawings made from a single viewpoint, the tower of St Saviour in Southwark (now Southwark Cathedral) Select image for the full panorama

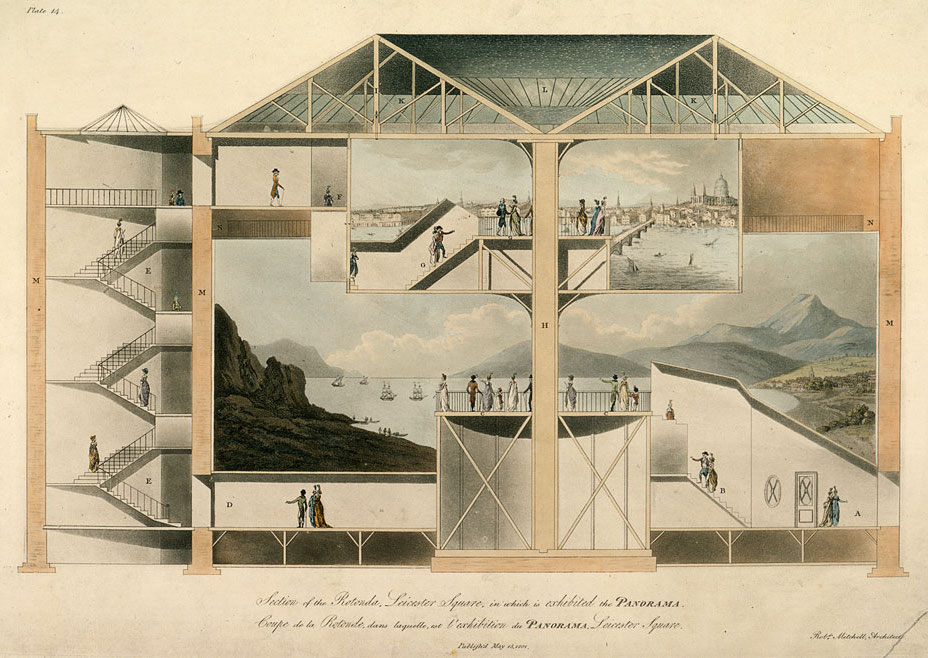

The panorama — patented by the Scottish portraitist Robert Barker in 1787 — consisted of a new method of displaying a landscape image. Barker’s proposal was to exhibit a painted landscape in a 360-degree view, on a circular canvas strip surrounding the viewer. This was not really a new kind of image: the manipulation of perspective, with multiple viewpoints made to appear visually consistent, was already a constituent feature of bird’s-eye views. Barker’s innovation was rather in the viewer’s interface with the image. The panorama was an apparatus that would isolate and control what it was possible to see. His specifications included lighting from above, an isolated central viewing platform exactly halfway up the height of the canvas, restrictions on the viewer getting too close to the picture, entrance from below, and ventilation without windows. The edges of the image were covered by a canopy that, at the top, also hid the source of light. Barker wasn’t taking the picture out of the frame, he was making the frame big enough to include the spectator as well.

Cross-section of the Rotunda in Leicester Square in which Barker's panorama of London was exhibited (1801)

Cross-section of the Rotunda in Leicester Square in which Barker's panorama of London was exhibited (1801)

To audiences anticipating a conventional bird’s-eye view, it must have been strangely thrilling to walk through a tunnel and up onto a viewing platform and find themselves entirely surrounded by an illuminated scene. Initial responses to Barker’s inaugural panorama in 1792, a view of Edinburgh from Calton Hill, compared it to recent feats of illusion and visual trickery, such as Philippe de Loutherbourg’s Eidophusikon. But Barker was emphatic in his wording when defending the show against these comparisons:

There is no deception of glasses, or any other whatever; the view only being a fair sketch, displaying at once a circle of a very extraordinary extent, the same as if on the spot; forming perhaps, one of the most picturesque views in Europe. The idea is entirely new, and the effect produced by fair perspective, a proper point of view, and unlimiting the bounds of the Art of Painting.

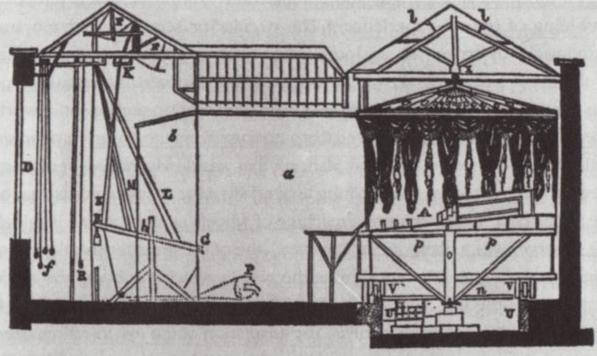

Barker’s insistence on the “fair” (twice), “proper” and artistic character of his panorama painting was a counterweight to the startling sense of hyperreality that must have been experienced by visitors. Barker and subsequent proprietors (after his patent lapsed in 1802) emphasised the verisimilitude of the scenes they presented, whether of cities or battles, and invited verification from figures who had visited the places or witnessed the events. Panoramas began not only to serve as a means of satisfying curiosity about the wider world when travel was difficult or impossible, but also to represent current affairs – The Battle of the Nile, the Coronation of George IV – in a time before illustrated newspapers had made up-to-date imagery cheap and accessible . Modifications of the viewer-scene relationship established by the panorama were also essayed. The moving panorama — a long painting revealed horizontally or vertically on rollers — became popular in the 1820s. Here the audience stayed in their seats and the image moved. Theatregoers in 1824 at the Theatre Royal watched Grimaldi the clown “ascend” in a balloon against a scrolling vertical panorama backdrop designed by Thomas Grieve. A different kind of movement was achieved by the “diorama”, invented in 1823, which worked by moving audiences between two different “sets” showing scenes from nature in changing time and seasons, the transitions effected by lighting.

Patent image of Daguerre's London Diorama, 1823

Patent image of Daguerre's London Diorama, 1823

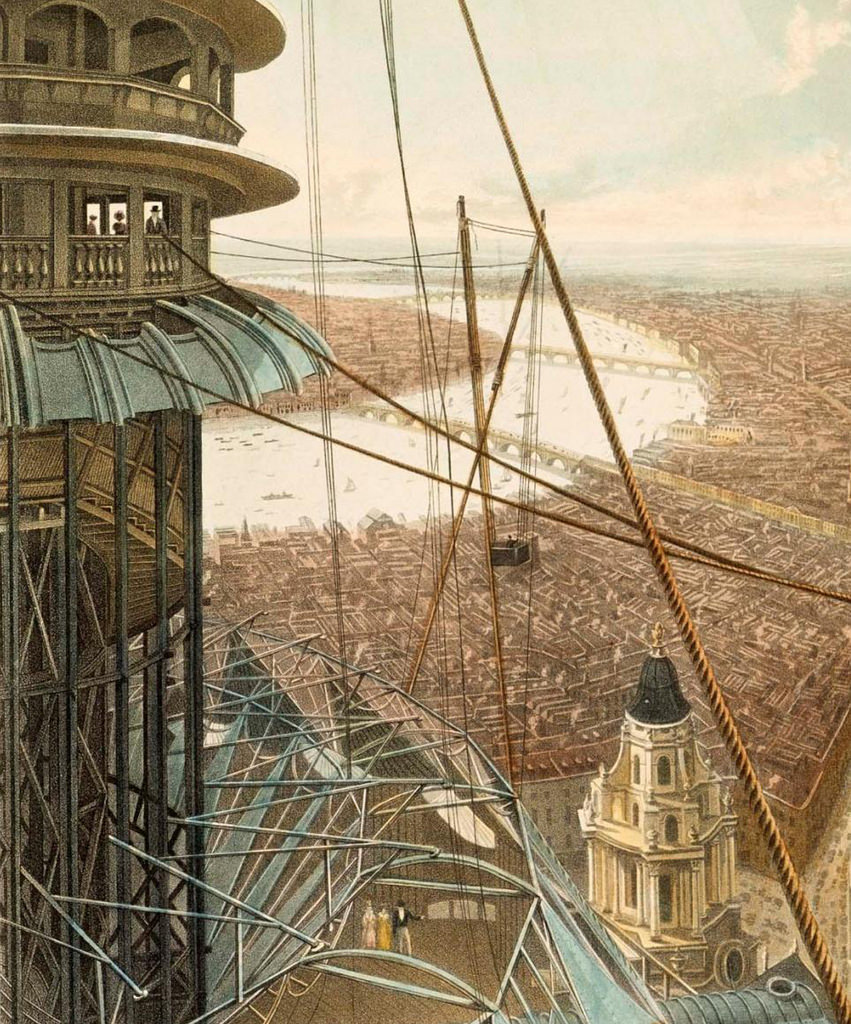

With the viewer at the centre of the view, the frame was dissolved. No longer was the experience of landscape representation mediated by the baroque perspectival constructions of traditional city views. The visitor was invited to encounter the landscape directly. Of course, this was still an image, but every effort was made to support the illusion that the visitor had been transported to the very point from which the image had been captured. Barker claimed the view was “the same as if on the spot”. Sometimes this “spot” was actually physically recreated in the panorama’s rotunda, to form the viewing platform, as is the case in the 1829 Colosseum Panorama of London from St Paul’s Cathedral. The structure of the model of the cathedral tower is evident in a contemporary engraving by Rudolph Ackermann.

Detail from Bird's Eye View from the Staircase & the Upper Part of the Pavilion in the Colosseum, Regent's Park (1829), a coloured aquatint by Rudolph Ackermann. The distant image of London you see is not a view to the ground below but rather the painted backdrop of the panorama

Detail from Bird's Eye View from the Staircase & the Upper Part of the Pavilion in the Colosseum, Regent's Park (1829), a coloured aquatint by Rudolph Ackermann. The distant image of London you see is not a view to the ground below but rather the painted backdrop of the panorama

But many of those entering the rotunda to admire the view found themselves disoriented, and it was not unusual for a first-time visitor to a panorama to be sick.

The disruption of the conventional relationship between viewer and canvas — the removal of the frame, the legends, the hierarchy that reminded the viewer where they stood — could induce a powerful sense of dizziness and nausea. Visitors encountered the limits of their own bodies by being immersed and yet unable to see everything at once.

The use of a conventional linear perspective both projected and demanded an observer situated at an exterior, elevated point; it was a way of making sense of the large space and depth of a city view. The viewer of the picture needed to occupy this ideal viewpoint, imagine themselves into the landscape, while they read the image. From the late eighteenth century the panorama modulated this scopic regime, by immersing the viewer within the image while maintaining a certain separation and elevation of viewpoint. The impossibility of seeing the whole canvas at once, and the emphasis on verisimilitude in what was evidently an illusion, generated a new awareness of the limits of vision. The panorama inaugurated a mode of vision that was more subjective and self-reflexive, in which the beholder described not so much what there was in the image, but what they saw there and what it looked like to them. It was a peculiarly appropriate mindset with which to experience the newly elevated view enabled by the hot air balloon, which made its first manned ascent in France in 1783.

The fact that the balloon and the panorama were invented within five years of one another, and the similarity of the 360-degree views they offered, is remarkable. In his The Panorama: History of a Mass Medium, Stephan Oettermann argued that the new visual experience gained in the balloon led to the development of a format for recreating the immersive view. He qualifies this claim with the suggestion that the panorama responded indirectly to more sophisticated demands on vision and representation, by no means all to do with the balloon. It is not, I think, a simple case of cause and effect, with the balloon coming first, nor did both devices emerge from the same set of circumstances, for example, the balloon’s uptake depended on the availability of hydrogen that had only just been successfully combined. But the panorama undoubtedly schooled its visitors in a mode of viewing that was compatible with ballooning. And though the balloon was five years older than the panorama, far fewer people directly experienced balloon travel than the tens of thousands who visited a panorama. Before 1836, a total of 313 people had ascended in a balloon in England by one contemporary compiler’s reckoning; in contrast, as an example, the Colosseum’s Panorama of London received more than that number in a single day during its 1829 season. In the first fifty years of these two technologies, the idea of the “panoramic” view was far more widely disseminated than the idea of the balloon view.

The impact of the panorama can be traced in balloonists’ accounts. Those trying to describe their airborne experiences found the panorama and its related devices to be a useful point of comparison. Before its appearance in 1792, authors of balloon accounts struggled for analogies to describe their experience. “I can find no simile to convey an idea of it”, wrote Vincent Lunardi of his elevated view of London. Thomas Baldwin was never lost for words, but flitted through analogies — fairyland, Lilliput, a table-top model of Paris, an “elegant Turkey-Carpet” — the only one bearing repetition being that of a “coloured Map”.11 Another 1780s balloon narrator also referred to “a coloured map or carpet” — the apparent flatness of the landscape was a new and unimagined feature of the aerial view. Both Lunardi and Baldwin related their views at one point to bird’s-eye views, mentioning “oblique” and “common” prospects or perspectives. But they insisted on the newness and difference of the view, and, in deference to Edmund Burke’s Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful (1756), professed a sublime-inflected inarticulacy at the vastness and beauty of the vista.

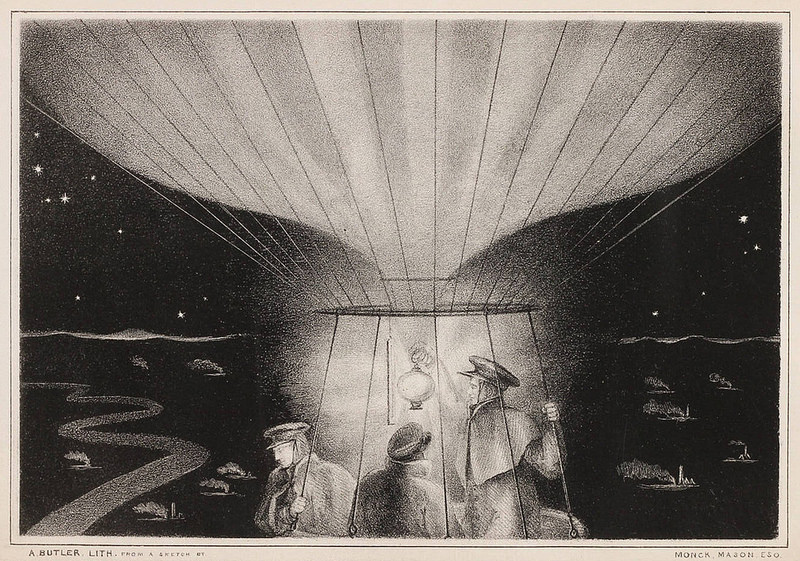

"Environs of Liege, Seen From the Balloon at Night", a plate in Thomas Monck Mason's Aeronautica (1838)

"Environs of Liege, Seen From the Balloon at Night", a plate in Thomas Monck Mason's Aeronautica (1838)

By contrast, in the first half of the nineteenth century, the heyday of the panorama, balloonists did not need to look far for an appropriate analogy. “We found ourselves… the motionless spectators of a vast panorama” wrote Dr. Forster of his first ascent. Henry Mayhew, the journalist and social reformer who wrote about his first balloon experience for the Illustrated London News in 1852, drew heavily on this new vocabulary:

And here began that peculiar panoramic effect which is the distinguishing feature of a view from a balloon, and which arises from the utter absence of all sense of motion in the machine itself. The earth appeared literally to consist of a long series of scenes, which were being continually drawn along under you, as if it were a diorama beheld flat upon the ground, and gave one almost the notion that the world was an endless landscape stretched on rollers, which some invisible sprites were revolving for your especial enjoyment.

The first sentence suggests that by the middle of the century balloon views were often described as “panoramic”. His references to a diorama and a moving panorama show these contemporary entertainment technologies providing a shorthand for the expansive scope and numerous points of interest available in a balloon view. They also presage the comparison between the aeroplane view and the cinema in the twentieth century. Both the balloon and the panorama educated observers in techniques of engaging with the image that anticipated cinematographic techniques such as tracking, where the camera moves through space, and panning, where the camera swivels on a stationary point.

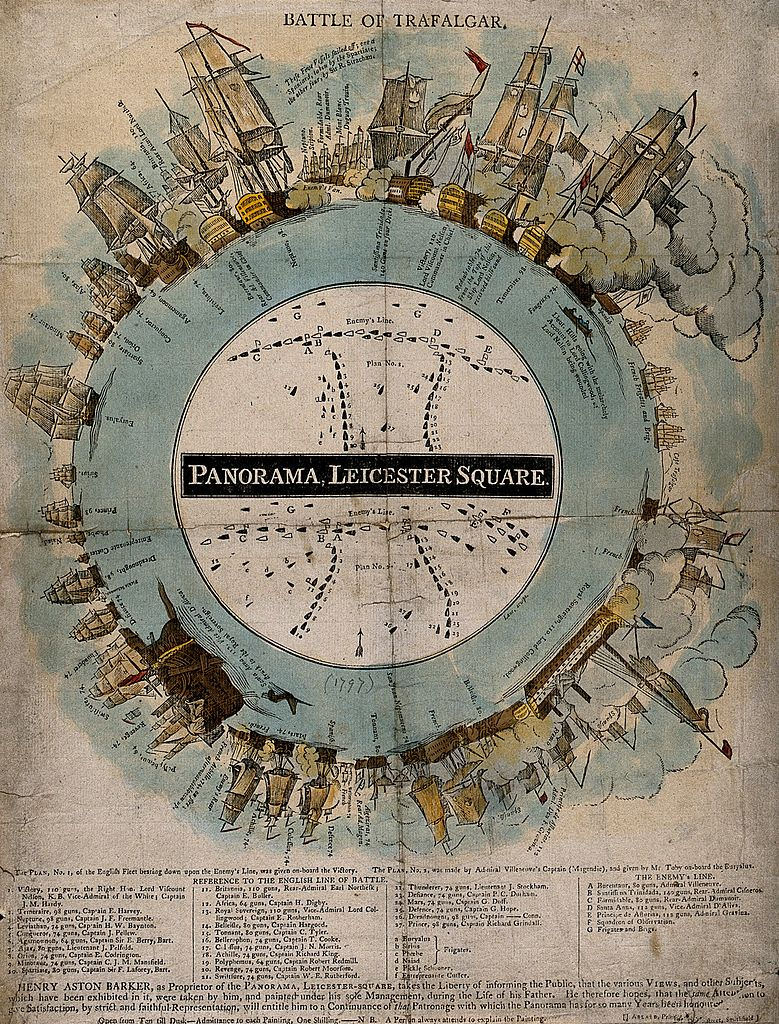

An advertisement for the Panorama, Leicester Square, London: showing the battle of Trafalgar. Coloured engraving by Lane, after H. A. Barker, 1806

An advertisement for the Panorama, Leicester Square, London: showing the battle of Trafalgar. Coloured engraving by Lane, after H. A. Barker, 1806

Mayhew flew in Henry Green’s balloon, the Royal Nassau, on its five-hundredth ascent. A professional balloonist with a mind for business, Green had constructed a giant balloon which could be inflated with coal gas (much cheaper than hydrogen) and begun a residency at Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens in 1836. His long distance balloon journey in the same year, an unprecedented 18-hour drift across Europe with two passengers (one of whom, Thomas Monck Mason, wrote a lengthy and fascinating account of the trip), brought welcome attention to the venture.

The ascents constituted a spectacle in themselves, drawing the attention of passers-by within the Gardens as well as providing the passengers with an exciting new experience — Mayhew noted “a multitude of upturned faces” as he ascended. As Richard Holmes notes, the cultural associations of the balloon changed in the 1830s, from the pioneering and dangerous image of its first fifty years to a more accessible “recreational” object. With a “passenger” balloon regularly ascending at Vauxhall, it became easier for the general public to experience flight. For a moderate fee, anybody could go up in the Royal Nassau and see the capital city from the air. Balloons joined panoramas on the London entertainment circuit; both types of view offered up the metropolis — the whole at once — to the gaze of the casual spectator. In 1839, it was even possible to go to Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens to experience, in a moving panorama, a simulacrum of the very balloon ascent made from the same site.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, the balloon experience had been well and truly disseminated. A map of London produced for visitors to the Great Exhibition was (inaccurately) named a “balloon view” to give it more appeal. The professional balloonist Henry Coxwell recalled that he was able to prepare for his first ascent, in 1844, simply by reading widely.

This, then, was my first real ascent; but such was the amount of thought I had bestowed on the subject in previous imaginary flights, built upon the descriptive accounts of others, that I seemed to be travelling an element which I had already explored, […]. In most respects I found the country beneath, including the busy humming metropolis, the River Thames, shipping, and distant landscape, pretty much as I expected, and had been tutored to see in the mind’s eye;

An important shift had occurred in the experience of landscape. The panorama and the balloon disrupted the previously rigid interface between spectators and their surroundings, by dissolving the frame of representations and bringing possibilities of height and movement to the viewing subject. Thomas Baldwin’s ballooning pictures were a rare attempt to reflect these possibilities, but were too strange and too new to make much impact. Some fifty years on from Baldwin’s pioneering ascent in 1785, many more people had experienced being at the centre of the view, in a static panorama, and a great deal more had been written to convey the visual rewards of aerial mobility. “[T]he aeronaut quits the earth to assume a station in the zenith of his own horizon”, wrote Thomas Monck Mason after the Nassau flight, where “all the most striking productions of art, the most interesting varieties of nature, town and country, sea and land, mountains and plains, mixed up together in the one scene, appear before him as if suddenly called into existence by the magic virtues of some great enchanter’s wand.” He brings to mind both a panorama and a diorama in his invocation of artifice. The new bounds of reality, visible from this suspended vantage point, were best articulated using the vocabulary of virtual reality.

This article was originally published by the Public Domain Review under CC-BY-SA licence; the original includes full sources and footnotes.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews