3.1 Seeing through machines

Crucially, this matters because when we make sense of digital data we are always doing so through a machine and not directly with our own senses. Metadata matters because what it records may result in bringing the text into sharper focus, blurring it, or hiding it from view. If readers can only retrieve what is in the library catalogue, and can never browse the shelves, then metadata becomes a gatekeeper and not simply a set of observable ‘facts’ about a text.

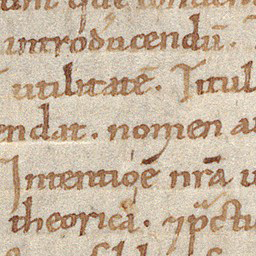

Medieval scholars developed a practice designed to guide them in asking sets of standardised questions to enable rigorous interpretation of texts. The accessus ad auctores preceded editions and commentaries of classical authors. As in our digital world, the accessus functioned as a kind of metadata standard which helped establish the provenance and reliability of the text and facilitated the traceability of the content across different media and locations, sometimes over hundreds of years.

Activity 4 Medieval metadata

Visit a version of the accessus ad auctores [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] . Find an item of digital content online (such as a webpage, an online video, a digital book or report). Can you answer these questions?

- Who (is the author) (quis/persona)?

- What (is the subject matter of the text) (quid/materia)?

- Why (was the text written) (cur/causa)?

- How (was the text composed) (quomodo/modus)?

- When (was the text written or published) (quando/tempus)?

- Where (was the text written or published) (ubi/loco)?

- By which means (was the text written or published) (quibus faculatibus/facultas)?

Discussion

If you chose a digitised version of a material book or document look again at the questions, did you answer them for the material or digital version? Are there any differences? Would being aware of these differences change your interpretation of the contents?