1.1 Throwing a spotlight on research in action

Case study 2.1 A glimpse into a classroom in India

A research and development project led by The Open University was carried out in India, where academics from the UK worked to support teachers to better understand their classrooms through carrying out video observations. Different subject specialist teacher educators from the UK worked with subject specialist teacher educators in India as part of the TESS-India (2020) project [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] (make sure to open this link in a new tab/window so you can easily return to this page). The teaching and learning contexts were chosen to become recorded assets for use by local teacher educators.

In Activity 1, you will watch one of the films in which children aged 14–15 years were being taught English as a second language in a school in Delhi, India. It features some students reading aloud and other students in pairs writing out, in English, passages from a book, and then correcting themselves.

Before filming, and in order to allow observation of such an activity, there are questions a researcher should ask:

- Should the observation be captured by filming?

- Would filming be considered overly invasive?

- Would it be more appropriate to do an audio recording of the activity, accompanied by field notes? Audio records can now be digitally identifiable, so this would not be better at protecting identities than filming, but could be less intrusive.

It can be difficult technically to record audio of different participants (and groups of participants) in a busy setting. Collecting good quality data is in itself an ethical issue: participant voices must be heard if the study is to do justice to those in the setting. In the activity, you will watch this video and have a chance to think about researcher choice.

Activity 1 Observation and researcher choice

Watch the four-minute long film of an Indian classroom referred to in Case study 2.1.

Transcript

NARRATOR: In this video, a secondary English teacher uses English to give instructions and to organise an activity. The activity involves students dictating short passages to each other in pairs. This kind of activity gives all students the chance to speak in English.

TEACHER: Now we are going to begin a dictation activity here where we're going to divide the whole class into pairs. Fine? You are a pair. You are a pair.

You are a pair. You are a pair. You, you, you, you all are divided into pairs.

This is A, this is B. You're A, you're B. You're A, you're B.

You're A, you're B. You're A, you're B. You're A, you're B. You're A, you're B.

Now, all the A's, please raise your hands. All the B's will raise their hands now. What is a dictation activity? That one is going to read out a passage, and the other one in the pair is going to write it.

If you're A, you're going to open your texts. Open your textbook. Turn to page number 23. And focus your attention to passage nine.

So A is going to read passage nine to B. Right? I'll give you a time limit of three minutes. After three minutes, I'll ask you to stop, and we are going to swap the rules. A can start reading now.

[STUDENTS READING]

STUDENT 1: In pursuit of his ambitions, he worked hard. We had to give him the credit-- hard.

STUDENT 2: He worked hard.

STUDENT 1: We had to give him credit--

STUDENT 2: Spelling?

STUDENT 1: He badgered--

STUDENT 2: Spelling?

STUDENT 1: B-A-D-G-E-R-E-D. The instructors with questions. With questions.

STUDENT 3: [INAUDIBLE]. Not only [INAUDIBLE], tireless.

STUDENT 4: [INAUDIBLE] is not [INAUDIBLE] at the end of [INAUDIBLE].

TEACHER: B will stop writing now. Now, we are going to swap the roles. Now, A will close their textbooks. Please close your textbook. All the A's will close their textbooks.

Now, B will open the textbook. Now, B is going to dictate, or read out, paragraph number 11. Be very clear with your speaking please so that A is able to understand what you are speaking, all right? Start.

STUDENT 5: With a ringing--

STUDENT 6: With a ringing--

STUDENT 5: Beautifully--

STUDENT 6: Beautifully--

STUDENT 5: Beaming.

STUDENT 6: Hm?

STUDENT 5: Beaming.

STUDENT 6: Beaming.

STUDENT 5: Comma. Inverted commas again. The professor will publicly correct him. Full stop.

TEACHER: All right, we stop here. We stop here. Stop writing, everyone.

Now, we are going to check what we've written. We are going to see whether we've written it correctly or not. And we are going to check it from the textbook itself.

Swap your notebooks, please, your work. Swap your notebooks. Open your textbooks right in front of your eyes. Whenever you were wrong, just circle it and correct yourself.

Then reflect on the following.

Think about:

- What are the possible research benefits of observing classrooms like this?

- What are the possible concerns those in the setting might have when researchers contact them to request permission to record a classroom session?

- What are the possible negative consequences that could result from collecting data this way?

- What steps can researchers take to minimise negative consequences?

- What options do the researchers have to maximise the benefits?

Discussion

There can be benefits from recording behaviours in particular settings. Recorded activities are often used when training teachers, doctors, social workers and nurses to aid reflection, to see the bigger picture of what has taken place than even those in the space at the time could sense, and to help prepare those who have not yet experienced such situations. Such recordings can be used for research to collect data about patterns of behaviours and the use of space within and across situations. This can lead to new revelations about what happens in these spaces, that wouldn't be possible just from those in the settings themselves.

However, by creating a record and sharing this with those who were not present, there are risks for those who have been shown in the recording. What they said and did can be seen by others they don’t know and may be used in ways over which they have no control. Their actions and words might be misinterpreted or used against them if considered inappropriate; for example, by employers. Researchers, as well as journalists and those using such materials for teaching, need to take responsibility for what is recorded and should prepare those involved in and affected by the implications for making data collection public. Researchers should respect the wishes of those being recorded (or those responsible for those involved) and limit how public the data is made, if they express reservations about making the data more widely available.

The main risk is in identification of the individuals present and/or the space, therefore impacting the right to privacy. Researchers can consider whether anything can be done to reduce the revelation of specific information in the space, such as ensuring no organisational-specific logos or branding are visible. However, this is usually considered to be too intrusive. Alternatively, only the backs of people can be shown so that their features are not considered identifiable, which would mean careful consideration of where the camera is placed.

Usually de-identification takes place by selection of which parts of the recording can be shared, or through digital manipulation, erasing features of people and places. Agreement as to what can be shared should always be gained.

Now think about another example of research in action to reveal additional considerations. Case study 2.2 refers to an individual researcher’s reflections on research aimed at understanding the needs and experiences of those who have been displaced across national borders by local conditions.

Case study 2.2 Who should be involved in research with displaced people?

Victoria is a humanitarian consultant and researcher whose work focuses on migration, voice and community engagement. Her narrative focuses on fieldwork experiences examining communication-as-aid with refugees and humanitarian workers in refugee camps on the Thai–Burma [Myanmar] border. She offers the following reflections:

The fieldwork formed part of a study that sought to understand the information and communication needs of refugees deciding whether or not to return to Burma [also known as Myanmar]. The majority of refugees in these camps were of Karen ethnicity, with smaller numbers of other ethnic groups, including Burman, Kachin, Mon, Shan and Rakhine people, represented…

Prior to commencing the fieldwork, I prepared an ethics application for the Institutional Review Board (IRB). Advice I received from academic colleagues was either ‘Give up. It will be impossible to get approval’ or ‘Treat the IRB process as a box-ticking exercise’. The first anticipated the risk-averseness of IRBs towards research with vulnerable populations. The second implied their decision need not prevent me from taking in-field decisions... After a stressful few months of back and forth, approval was granted.

In reflecting on the role the IRB had played in ‘approving’ my study, I appreciated how this manifest an imperialist epistemology. The IRB appointed itself as the arbiter of ethical practice with the refugee communities I was to study—irrespective of the degree of knowledge it possessed about the studied groups. In requiring that I seek ethics clearance before traveling to Thailand, the approval process did not demand nor support me in incorporating into my application the perspectives of members of the refugee communities themselves. It was not possible—due not least to the lack of internet access in the camps—to build relationships with refugees prior to arriving in Thailand.

Instead, I sought input from several aid agencies working on the Thai–Burma border. Whilst international aid workers typically live and work in locations far from the camps and have very little contact with the refugee communities, they are accessible from Australia via Skype and email…

If IRBs seek to promote research ‘for’ and ‘with’ refugee communities— and thereby do more than simply equipping institutions with a legal safeguard against liability—they must find a way to ensure that the voices of the displaced are heard in the research process. In the field, ethical challenges different to those anticipated in my ethics plan arose on a regular basis. For example, I became aware of the limitations of my approved approach to participant recruitment after learning about the frustrations held by refugees from non-Karen backgrounds as feeling excluded from refugee leadership and organisational structures. By recruiting people through committees, I accessed Karen perspectives but concealed the voices of those who viewed themselves as marginalised in the camps…

It is possible to address unanticipated ethics issues by applying for a variation to the approved ethics plan…This was again a protracted approval process, preventing me from nimbly adapting—in consultation with members of the refugee communities—to further ethical problems as they became apparent. Furthermore, the delays created a financial burden for me as a self-funded postgraduate researcher, forcing me to extend the duration of the fieldwork and face the prospect of financial penalties if I submitted my thesis beyond my agreed registration period. The threat of such consequences creates an incentive for researchers to comply with a pre-approved IRB ethics plan.

In Activity 2, you will imagine yourself as Victoria and think about all those who influenced and are affected by her research.

Activity 2 Micro, meso and macro layers of involvement in research

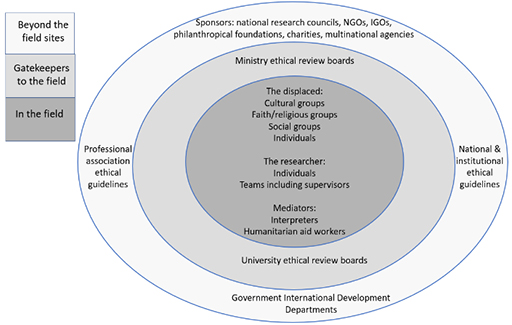

In Case study 2.2, Victoria described the need to be involved with a range of other individuals and groups in trying to carry out her research with displaced people. This involved her acknowledging her responsibilities and building relationships.

On a piece of paper, draw three concentric circles with:

- a.the inner circle for those likely to be involved in research with refugees ‘in the field’ – a microscale for the study

- b.the second circle out from the centre for the gatekeepers needed to get ‘access to the field’ – a mesoscale for the study

- c.the outer circle for those ‘beyond the field sites’ who are related to, affected by and affecting the study at its macroscale

Within each circle, note down individuals you think may have been relevant to Victoria in her research. Then click on ‘Reveal discussion’ to view an example of those you might have included.