3.1 Sacred I: The Byzantine Church

According to Saint Germanos, Patriarch of Constantinople between 715 and 730, ‘the church is the earthly heaven in which the heavenly God dwells and moves’ (Acheimastou-Potamianou, 1987, p. 38). During the long life of the Byzantine Empire (330–1453), a number of architectural church types were developed to host and facilitate the liturgy, the religious rituals and worship. Some periods showed preference for larger-scale church buildings, while others favoured smaller-scale construction, especially during the late Byzantine period (1261–1453), which has sometimes been associated with the dire and declining economy of the Empire (see the downloadable document Appendix 1 [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] ). Regardless, size in no way affected the symbolism embodied in the construction of an Orthodox church. A standard Byzantine church faces eastward. In a large-scale construction, the edifice is fronted at the west end by a narthex, which represents the things that exist on earth. It is followed by the nave in the middle, which represents the things that exist in Heaven, and finally the sanctuary or holy bema, which represents the things that exist above Heaven. The latter is only accessible to the clergy and off limits to any form of female presence, except images of the Virgin.

According to the esteemed Byzantine scholar Otto Demus:

a Byzantine building does not embody the structural energies of growth, as Gothic architecture does, or those of massive weight, as so often in Romanesque buildings, or yet the idea of perfect equilibrium forces, like the Greek temple. Byzantine architecture is essentially a ‘hanging’ architecture; its vaults depend from above without any weight of their own.

The latter element is a very important contribution to the concept that the Byzantine church is the earthly heaven, since, once inside the building, the boundaries where the man-made structure ends and sky (or rather the illusion of it) begins have evaporated through this ‘weightless hanging’. In modest-scale constructions, the importance of the lacking dome and vaults is transferred to the vault of the sanctuary apse and the barrel-vaulted roof that also convey this ‘hanging’ element. Icons, in the broader sense of the word, form the iconographic programme that decorate all spaces of an Orthodox church.

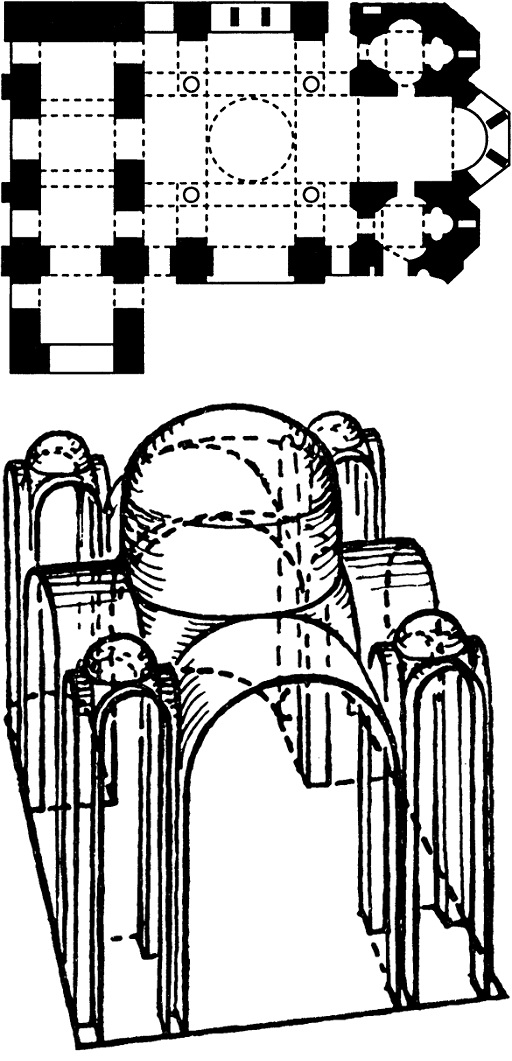

One of the most popular and standard forms in Byzantine architecture was the ‘cross-in-square’ or ‘inscribed cross’, evident from the ninth century onwards (i.e., from the Middle Byzantine period – see Appendix 1). Its plan has nine bays, the central one with a dome carried on four columns; this is supported by four bays, usually barrel-vaulted, which form a Greek cross (hence its name ‘cross-in-square’) with the dome effectively buttressed at its centre; four small corner bays complete the square outline (Figure 5).