3.1 On love: growing ethically with others

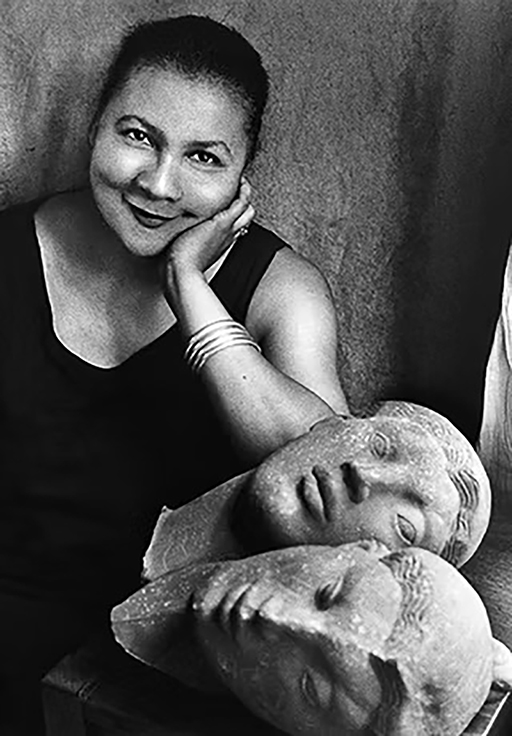

The feminist author bell hooks dedicated a significant portion of her career to outlining a theory and practice of love. Expanded upon over three books, hooks provided a framework for how we can all live joyful, meaningful and ethical lives. Her work includes romantic relationships and family but extends further to incorporate friendships and collaborations.

hooks states that love is frequently misunderstood and misappropriated as only equating to a feeling of affection and/or attraction. This is a limiting view for two reasons. The first is that it is superficial. The second is that it allows for restrictive and, worse, abusive relationships. All kinds of destructive and harmful behaviours can be enacted in the name of love.

This is why hooks insists that love is a practice rather than a feeling. If you accept that love is something that needs to be actioned for it to exist, you assume ‘accountability and responsibility’ for it (hooks, 2016a, p. 44). Love needs to break free from only standing for affection and attraction to include ‘various ingredients – care, affection, recognition, respect, commitment, and trust, as well as honest and open communication’ (p. 36). Later in the book she adds more practices, namely knowledge and responsibility. When you combine all of these practices, you abide by a definition of love that is ‘the will to nurture our own and another’s spiritual growth’ (p. 37). These are practices that we can all develop and become better at.

Being open to love can be difficult, particularly in societies where certain people must continue to fight so hard for respect, equality and justice. hooks dedicates a whole book to the struggle of Black people to experience and give love (hooks, 2016b). hooks makes the case that in the US, routine violence and racism experienced by Black people at the hands of white people has led to a general (but not universal) hardening of attitudes in relation to society and personal relationships. She charts this as a move from love to power within Black civil rights struggles. While the US has its own particular features, there is no doubt that police brutality and other forms of racism in the UK are bound to take their toll on the feelings of victims.

hooks does not advocate for blindly trusting others. On the contrary, her account of love is a mutual process between people – other people have to show themselves capable of giving and receiving love. The same could be said for self-love, another important theme for hooks. Loving oneself is not selfishness, but giving yourself permission and space to adapt and grow, while also asserting yourself as an important and equal person within your society.

The implication of an emphasis on love is that it’s a practice that should be encouraged to develop widely within groups, communities and then societies. Love therefore has a revolutionary potential.

This is so for two reasons. First, because loving practices – care, affection, recognition, respect, commitment, trust, honest and open communication, knowledge, and responsibility – are so central to the experience of being human. Repressing these under antagonism, greed and violence is to disavow human joy itself. Second, because these practices contradict many of the behaviours taught in organisations and societies, where we are pushed to compete relentlessly against other people, to care about self-image more than the good of the community, to chase short-term and superficial pleasures.

hooks’ case is that most people do not want to live like this – rather they yearn for love. We can start this journey of challenging power by looking to ourselves and those we can team up with in leadership, because by ‘intensely connecting with another soul, we are made bold and courageous’ (hooks, 2016a, p. 220).

Activity 3 Where is the love?

Adopting hooks’ definition of love can be a difficult process of realisation and reflection. It encourages us to consider whether we have been true to those people we have expressed love towards. It also leads us to think about the ‘love’ that we have received, and to re-evaluate whether that love would pass hooks’ definition. Such thoughts can lead to difficult reflections.

There are three things to say in response. The first is that love is a relational process for hooks – it requires mutual understanding of the meaning of love. If one person loves but the other does not, this is not a loving relationship, and growth between people is impossible. Secondly, love requires practice – you keep trying until you become good at it. It is not instantaneous. Thirdly, love is enabled and restricted by social, economic and political forces – often when people are unloving, it isn’t because they are necessarily bad people, but it could be because they have spent their lives starved of love. This is not the same thing as saying that you need to give predatory people more chances – absolutely not. Rather, you gravitate to people and situations that seem open to the mutual growth demanded by love.

So, this activity invites you to reflect on hooks’ words and find other people to talk them through with. This process never really ends, so there is no need to place a time limit on this activity – you have the rest of your lives.

Box 1 Love and Ubuntu

hooks’ emphasis on love is in line with an ancient sub-Saharan Ubuntu worldview. Johann Broodryk suggests that Ubuntu is underpinned by ‘intense humanness, caring, sharing, respect, compassion and associated values, ensuring a happy and qualitative human community life’ (2002, p. 56). Nelson Mandela concurred with hooks’ love message and suggested that we should promote love across the society because we are ‘all branches on the same tree of humanity’ (2006, p. xxv). Archbishop Desmond Tutu went further, stating that love should define what it means to be a person: ‘open and available to others, affirming of others, does not feel threatened that others are able and good; for he or she has a proper self-assurance that comes with knowing that he or she belongs in a greater whole’ (1999, p. 34-35).

Love and Ubuntu informed the establishment of the Post-Apartheid South African Government’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) that was chaired by Tutu. The TRC was established in 1996 to help heal the wounds of the Apartheid regime that treated Black people as third-class citizens and the rebel movements, including uMkhonto we Sizwe (affiliated with the African National Congress and founded by Nelson Mandela among others), as criminals. To embed love in their activities, rather than prioritising retribution for the perpetrators of crimes, the TRC adopted the restorative justice approach. Doing so allowed the perpetrators to confess their actions before the relatives of their victims, and in exchange they could seek forgiveness and ask for amnesty. Restorative justice was prioritised over the victor’s justice. In 2000, the TRC was replaced by the Institute for Justice and Reconciliation.