3 Becoming informed

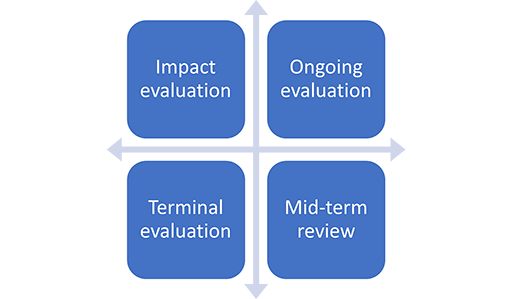

Evaluation is about generating evidence of practice and how effective it is. But it is also about making judgements about the value of the evidence, and the knowledge it gives rise to. There are various stages at which evaluation can happen as shown in Figure 2.

It is important to recognise that the knowledge created in an evaluation is not as certain as proponents of the RBM approach would have you believe. This approach to evaluation rests on the notion that it is possible to achieve value-free, objective, rational and certain knowledge, and that such knowledge can inform evaluations.

However, there are aspects of life and the human experience that are not reducible to scientific description and yet are meaningful and important to human well-being and are, indeed, at the heart of many development interventions. Moreover, some kinds of knowledge tend to be prioritised over others, for example, scientific knowledge is invariably prioritised over local knowledge. The latter may hold unwanted truths, or indeed, multiple truths.

RBM is based on scientific evaluation, which produces facts, measured through supposedly objective procedures and manipulated into causal relations. The facts can then be deemed to ‘speak for themselves’, which legitimates supposedly objective management and policy decisions, and makes redundant the need for judgement-making about worth and value. This gives rise to a single truth for those that have commissioned the evaluation, upon which they will make further resource allocation decisions, perpetuating the ‘cycle of certainty’. But the objectivity and impartiality of the knowledge produced by the scientific method are only ever partial.

It is important that the role of judgement is not excluded from evaluations, and that evaluation brings different voices and different perspectives into play. This will change how development management is understood and practised, being prepared to expose both the limitations of development management and its capacity for bringing about bad, as well as good, outcomes. Evaluation is the most powerful tool in challenging dominant or established interests, values and practices. It needs to be as rich, enlightening and challenging as possible if it is to serve its true purpose.