3 Mapping: redrawing the world

Maps have long been central to how empires are created, governed, imagined, and represented. The map is an integral part of the imperial claim. Mapping, and more broadly, the ability to dispassionately observe and record was seen by eighteenth-century Europeans as evidence of their superior civilisation (Edney, 1997). Knowing and claiming was also linked.

A common reaction to an old map is to compare it with what we know, to check how ‘accurate’ it is. But a map is not a mirror of nature; it communicates knowledge through representation. We need to think both about the knowledge that is being transmitted (including how accurate it is) and the process by which this is done.

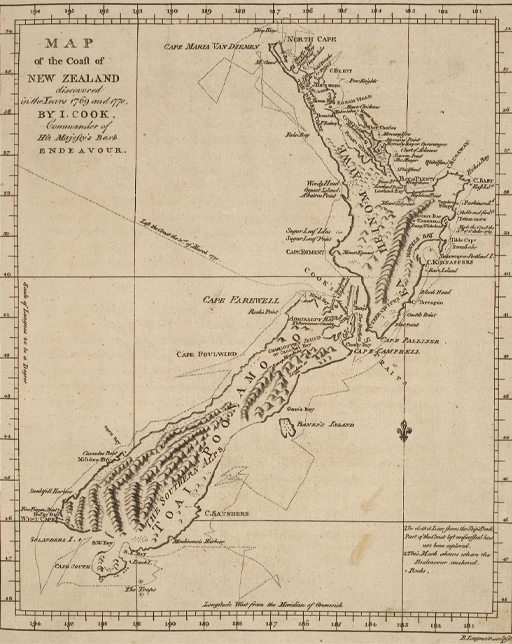

To explore further the politics of map making we are going to look at Captain Cook’s mapping of Australia. Cook was a skilled cartographer who tried to chart what he and his colleagues observed. The naming practice they adopted were part of this way of seeing the islands: this was a pristine new world for them to discover and name.

Cook’s expeditions were also encounters with local peoples. Cook’s map included some information gained from such encounters. It used, for instance, English transcriptions of Māori names for the two main islands. Cook was keen to question the indigenous inhabitants about place names so he engaged a translator – Tupaia – who travelled with him from Tahiti. Tupaia was not just a linguist, he was also a tahu’a (high priest), a bearer of religious knowledge, political advisor, and navigator (Salmond, 1991). Cook followed a route proposed by Tupaia who was able to draw on a huge body of Polynesian knowledge about navigating the southern Pacific. Tupaia’s ability to converse with the Māori inhabitants was based on this earlier age of exploration.

Cook and his companions were impressed by Tupaia’s navigational skills, which were rooted in a knowledge of the stars, winds, and currents. Some of his knowledge of Polynesian islands is contained in several maps and lists of islands within the archives of Cook’s expedition. Although we do not know precisely how these maps were compiled, historians Lars Eckstein and Anja Schwarz have suggested they can be understood as an attempt by Tupaia to map his knowledge of the islands of Polynesia according to European mapping conventions. Tupaia, they argue, was ‘a unique cultural intermediary whose ability to translate one highly complex system of wayfinding … into a very different order of knowledge far exceeded the abilities of any of his European interlocutors’ (Eckstein and Schwarz, 2019, pp. 90–1).

Reflecting on Cook’s map we can see that it is both a tool – allowing Aotearoa/New Zealand to be found again and for ships to navigate its shores – and a representation of British ownership. It proclaimed Cook’s discoveries, and the naming conventions symbolised British possession. Most of the names given by Cook are still in use. Eventually, the process set in motion by Cook’s expedition was to lead to the occupation and settlement of the islands.

Activity 3 Imagining empire

Please look again at the map above (Figure 4). Jot down the place names that you see. Make a note of anything you would expect to see that is absent.

- What does the map tell you about how Cook imagined the territory he was seeing?

Discussion

The only features shown are physical ones; no settlements have been marked. Cook presented the land as an empty place which made it easier for the British to claim it for themselves. This is reinforced by the names he chose. Apart from the two main islands, nearly all the names are English. This enabled him to render strange lands familiar – once they were knowable could they then become habitable? Other features are named after members of the crew: as well as the Cook’s Straits, there is an island named after Joseph Banks who went on the voyage. Deciding what the name for the lands should be and then imposing it was one way of claiming ownership.