2.2 Power over space

Space has always been used to enact power. Historically, corporate power worked on the bodies of Black people through capturing and enslaving them – forcing them out of their home spaces to toil and die in foreign spaces. Segregation works by applying restrictions on who can and can’t enter certain spaces. However, power can also work on space to open up possibilities for equity – for example, by building residential accommodation and social infrastructure in ways that enhance sociality and participation.

It is possible to think about how power works on and through space at a number of different scales.

Global power

Globally, the ‘dispossession’ of land and resources from people in colonised spaces has been, and continues to be, significant for how economies function globally (Harvey, 2019). Capitalism, to a degree, is premised on uneven spaces, with certain spaces exploited so that others can flourish (Smith, 2010). Even though such power dynamics stretch across global spaces, their effects are felt on bodies in specific spaces. For example, cobalt mining, which is essential for rechargeable batteries in products such as smartphones, laptops and cars, is an industry built upon the ‘modern-day slavery’ of miners in the Congo who ‘do extremely dangerous labour for the equivalent of just a few dollars a day’ (Gross, 2023).

The bodies of one group of people (miners in this case) are placed in precarious positions so that bodies in other spaces can experience more freedom – to communicate, to move around. The counter to this position is that enthusiastic supporters of global trade maintain that it ultimately improves the standard of living for everyone and that more time and regulation are needed to allow international market forces to run their course, delivering prosperity for more people.

Another key global spatial dynamic is what the geographer David Harvey (2018) refers to as the ‘spatial fix’. This means the tendency of corporations to keep moving through space to maximise profits. The most obvious example of a spatial fix at work can be seen in the relocation of factory production to maximise cheap labour. Such movements can leave communities in the UK and other post-industrial contexts gutted of meaningful economic activity. Meanwhile, workers in newly ‘fixed’ spaces abroad save corporations money by working for worse terms and conditions.

As Harvey (2019) states, this movement is continuous. As workers in new spaces (e.g. China) develop more power through organising and succeed in improving their pay and conditions, so corporations continue to move in search of cheaper options (e.g. from China to Vietnam) (Braw, 2022). You can also think of the spatial fix as working in relation to technology. As digital technology improves, it becomes possible for corporations to employ more people remotely, in locations where it can pay lower salaries. Artificial intelligence is an extreme version of the spatial fix, because it involves replacing people with software programmes that can learn and adapt.

National power

Governments use their spending power to stimulate economic activity in sectors deemed of strategic importance. Hence in 2023 the UK government’s Levelling Up Fund distributed £2.1bn of funding to projects it believed held the possibility of boosting economic activity – funding a range of projects in the areas of tourism, artificial intelligence and transport, amongst others (UK Government, 2023). Governments can also use their national power to invest in public services. National investment from government shapes local spaces – providing jobs and infrastructure that support some activities over others. National housing policy and legislation leverages power over how people live. For example, legislation introduced in the UK in 1980 by UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher gave tenants of council homes the right to buy their properties – which allowed a growth in the number of home owners, but also a national shortage of affordable housing for people who either could not or did not want to own their own homes.

Local power

Power works on space through shaping cities and neighbourhoods in its image. Hence in addition to cities growing, their spaces can also be repurposed over time, depending on economic forces and the commitments of local political leaders. One of the effects of urban spaces changing as a result of economic forces is referred to as ‘gentrification’.

Gentrification

The phenomenon whereby former working-class areas of cities are changed and adapted to the lives and lifestyles of the better off is commonly known as gentrification. The dynamics of gentrification are extensively discussed and debated by academics and policymakers, although broad agreement exists that gentrification has both significant economic and cultural aspects. Economically, residents are forced out of certain areas of cities as rents rise and the cost of home ownership becomes unattainable. In the UK, gentrification tends to work from the centre of cities outwards, meaning that people are pushed ever further to the peripheries of cities, forced to travel greater distances to work. However, an irony is at play in the fact that the process of gentrification tends to feed off an existing culture that long predates it (Harvey, 2019). The food, craft, music, art and broader social practices established by Black people in certain parts of a city are marketed as part of that area’s core appeal, which is leveraged to push up rental and purchase prices. The outcome is that the very people whose identities and practices were drawn on to increase profit are also the same people who are forced to move away.

Local councils have power to determine how space is used in a particular area – to develop spaces for people to socialise, receive information, learn, live, and so on. However, councils are also restricted by national legislation and available budgets, meaning that their discretion is often curtailed – for example, councils might want to build more council housing but legislation prevents them from borrowing enough money to build to the scale they would like. Reductions in the budgets of local councils mean that local spaces can become more shaped by private, corporate entities than the public sector. One example of this tendency to privatise public space is the selling off and closing down of public toilets in city centres, meaning that to go to the toilet, people increasingly need to purchase something in a café, restaurant or bar (Smolović Jones, 2022).

It can often feel that changes to local spaces are driven by economic powers so large that it is impossible for local people to do much about them. But that is not always the case, and there are many examples of successful leadership of local spaces that you can learn from.

Activity 2 Community leadership

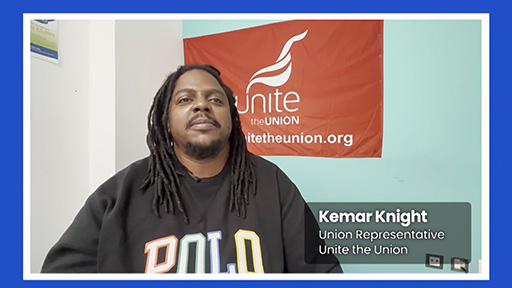

Watch the following interview with Kemar Knight, who talks about his work as a Unite trade union representative at the Park Royal Bus Garage. In the interview, he explains Unite’s approach to building collective forms of power to represent the members. As you watch the video take notes of the practices highlighted by Kemar in building collective forms of power.

Transcript: Video 1 Kemar Knight – Building collective forms of power

Comment

At the heart of Unite’s approach is building collective forms of power amongst people who learn to fight for themselves. They work towards a position where people are less reliant on representation from others – such as MPs, councillors or professional organisers – and instead can work together to make change happen.