2.3 Power over life

One way of making sense of power that affects the body is the concept of ‘necropolitics’. The term was devised by Achille Mbembe (2019) as a way of describing power that determines how certain groups of people are made more deserving of being alive than others. Mbembe’s case is that certain people are identified by those in power as scapegoats for a society’s problems, and are dehumanised, marked as less deserving of life. Hence people in many societies are given the status of the ‘living dead’ (Mbembe, 2019, p. 92), their lives considered more disposable and of less value than others. Historically in the UK and other contexts, Black people have been victimised by such necropolitics, subjected to abuse by dominant powers.

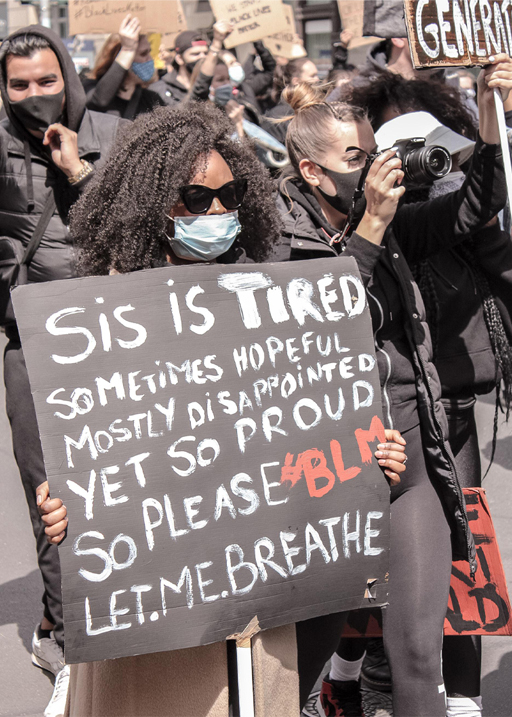

Necropolitics can also be understood on a global scale as tied to colonialism. A sense of misplaced superiority seems bound up with this legacy, with those who have benefited from the exploitations of colonialism feeling entitled to the resources and lives of people in colonised contexts. In the UK and other contexts the most obvious examples of necropolitics are found in the policing and criminal justice systems, with Black lives being made to count for less than white lives. Indeed, Black Lives Matter is a movement whose main focus is on a person’s right to life – power at its most fundamental.

However, necropolitics is not restricted to a UK or US context – its dynamics can be identified globally. One example of such necropolitics can be found in the way that migrant workers are treated in Russia. In their study, Round and Kuznetsova (2016) highlight Russia’s dependency on foreign labour, largely from Central Asia, for performing essential, precarious and dangerous work. Yet foreign workers are also made a scapegoat by the government, demonised as responsible for the country’s problems. The authors therefore identify a contradiction experienced by people who are made victim of necropolitics. On the one hand they are made hyper visible – demonised as causing a country to lose its values, resources and identity. On the other hand, foreign workers are made invisible when it comes to accessing welfare, employment rights and public services, with government and employers using their positions of power to deprive workers of essential protections and services. The dynamics of necropolitics identified by the authors in Russia will be recognisable in many other national contexts.