1.2 Four Is of resistance

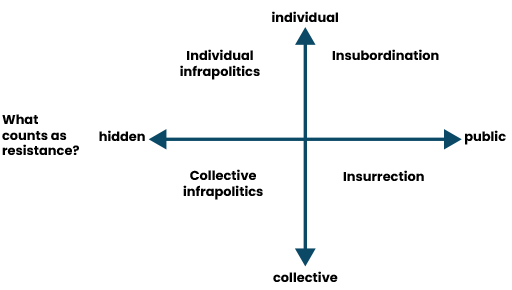

The map of resistance generates four forms of resistance, with each sitting in a particular quadrant of the map, as shown in Figure 5.

These different types of resistance are referred to as the ‘Four Is’:

Individual infrapolitics

Resistance that is hidden and individual. Infrapolitics is a word meaning political activity that is concealed from open view. The identity of the resister in this type of resistance would be secret, and the effects of the act of resistance more or less effective depending on how many people engage with it and take resistant action themselves as a result. An advantage of this kind of resistance is that it can be difficult for the dominant power to stop, but can nevertheless galvanise wider agency for resistance. A disadvantage could be lack of reach and impact, as there are limits on what an individual working alone can achieve. A good example of individual infrapolitics could be a whistleblower publishing an anonymous blog article exposing wrongdoing in an organisation.

Collective infrapolitics

Resistance that is hidden but collective. Such resistance is common where you have a network of people organising behind the scenes, usually under the radar of the powers they resist. Technological developments in messaging and web software have made such resistant organising easier over time. Indeed, trade unions rely on collective infrapolitics to connect workers and share experiences. An advantage is that the hidden nature of collective infrapolitics can provide a safe space where people can explore sensitive topics and gain reassurance from others – as has been the case with the Everyday Sexism Project, which enables women to share experiences and plan action without experiencing sabotage from the powerful men they are resisting (Vachhani and Pullen, 2019). A disadvantage of collective infrapolitics could be that the actions of the group remain limited by their secrecy if they are unable to openly challenge power.

Insubordination

This is an individual and public form of resistance. Others can see the identity of the resister, who is openly oppositional. Most obviously in recent memory is the example set by climate campaigner Greta Thunberg. Her global Fridays for Future movement of young people taking strike action from school started as a solitary but public protest from Thunberg, as she sat outside the Parliament building in Sweden protesting the lack of action from political parties on the climate crisis. A whistleblower could also be a good example, if that person exposed wrongdoing publicly, such as through the media. As an advantage, such public but individual demonstrations of resistance can be powerful in providing a symbol of hope to others – the David vs Goliath underdog figure. Such resistance is more or less effective depending on how many people relate to it and join the cause. Insubordination, however, can also be isolating and expose the resister to hostility, even danger.

Insurrection

This is resistance at its most public and collective. Strike action or street protest are excellent examples. The effectiveness of insurrection is measured by the degree to which it manages to force concessions from those in power or whether it enables resisters to take power themselves. There are of course risks. Sometimes it is unclear where the leadership comes from and what the strategy is, because power is shared by so many people. However, a large body of people, if properly organised and led, can provide a powerful mass that can be hard to ignore. In the case of strike action, it is the number of people refusing to work and the disruption caused, combined with how long they are prepared to go on strike that can determine success – it is then a matter of which side concedes first. Insurrection is not necessarily aimed at demanding concessions from an organisation, but can instead try to harm or destroy it if the organisation’s ethics are considered to be beyond repair – the practice known as dissensual leadership, which you explored in Week 3 (Barthold et al., 2022). Climate activists using their bodies to prevent fossil fuels being extracted is one example of such leadership, likewise direct and peaceful action from race equality campaigners.

Groups rarely stick to only one form of resistance. They can move between the four quadrants over time. This is usually from individual and hidden to more public and collective – as was the case with Greta Thunberg and her movement. However, the direction of travel can migrate the other way – an example may be collective action on racial equality inspiring individuals to take action (private or public) in their workplaces and/or communities.

You will now practise identifying types of resistance by engaging with a real example.

Activity 2 Identifying resistance types

In this video Kemar Knight discusses limitations of individual complaints (individual infrapolitics practices). As you watch the video, try to identify one or more of the Four Is.

Do the experiences in the video speak to your own? If you wanted to start some resistance leadership in your own context, which of the Four Is would you choose? Make some notes about your thoughts.

Transcript: Video 1 Kemar Knight – Limitations of complaints

Comment

There is no right and wrong answer to which type of resistance you should apply to your own context. What is worth noting in conclusion, however, is the fact that individual resistance rarely gets substantial results in and of itself. At some point in time, if resistance is to win, it nearly always needs to become more collectivised so that it can build more power.

The framework offered by Mumby et al. (2017) is a useful one, but it does not cover all types of resistance. You will now move on to consider a framework that defines types of resistance according to how they respond to power.