2 Belief in an afterlife

Why, it might be asked, did the ancient Egyptians in general, and Nebamun in particular, go to such extraordinary lengths to construct and decorate their own private tombs?

One of the most persistent modern myths about ancient Egypt is that it was a culture obsessed with death. In fact Egyptian art is full of the details of life as it was lived by human beings on Earth many thousands of years ago, and the artefacts that have come down to us indicate a keen appreciation of the good things in life, at least for the elite. At the same time, however, it would be futile to claim that ancient Egyptians were not concerned with ensuring their rebirth into the much-desired afterlife.

Key point

The important point is two-fold:

- that the modern distinction between sacred and secular scarcely applies, the whole of life was imbued with a spiritual dimension involving gods who were ever-present

- that an Egyptian conception of the afterlife was closely modelled on the fears and hopes, needs and desires experienced in life on Earth (Figure 6).

We have to be careful not to impose a Christian conception of life on Earth and life after death (not to mention a modern secular concept of life on Earth and nothing after death) upon Egyptian representations of their beliefs about humans, gods and what happens to the human body (as well as to the more intangible aspects of life) after the individual has died.

One thing in particular is of note. In a Christian conception the body tends to carry negative connotations and to be associated with sin, whereas notions of a reward for a good life in heaven tend to be couched in rather more ethereal terms. A case in point would be the contrast between Dante's Inferno (Figure 7), where most of the torments are resolutely and literally corporeal, and his Paradiso, where the experience of ascending into heaven is described in predominantly abstract terms of light and colour. The ancient Egyptians, however, (and once again one has to make the qualification that here we are speaking about the well-to-do) seem to have combined an abstract ‘spiritualised’ element with an altogether more worldly aspect.

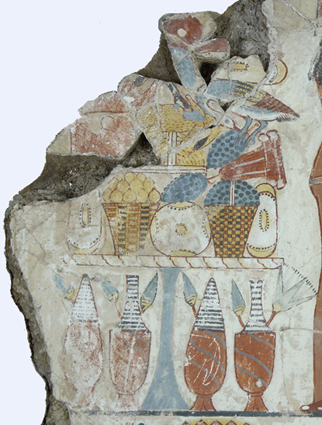

At one level, the ancient Egyptians held ideas of posthumously joining the cosmic cycle and becoming one of the ‘imperishable stars’, while at another, they regarded their afterlife as being, at least in part, an idealised continuation of life on Earth: food, drink, sexual love, luxurious surroundings, even down to the matter of having adequate supplies of servants to do all the work (Figure 8).