2.2 Reconstruction

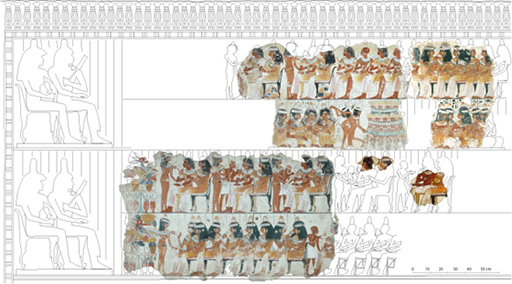

Look now at the speculative reconstruction of the entire wall (Figure 11). What is immediately noticeable?

The scene is reconstructed on the basis of evidence from other tomb-chapels. It is likely that each of the two main groups, the top two registers and the bottom two, would have been directed towards two over-sized figures of Nebamun and his wife, to whom the guests are, as it were, paying their respects. It could be a representation of Nebamun’s funeral/wake itself, or a banquet in his honour at one of the festivals for the dead held annually in the valley. The overall effect – of the registers, of the differences in scale across the composition as a whole – is to push the decorative scheme towards stylisation. Yet to the modern viewer, these kinds of non-realistic conventions of the mise-en-scène (composition of the scene) are counterbalanced by the dramatically realistic details that capture our attention.

It is as if one aspect of the technique and decorum of Egyptian art pulls us towards an acknowledgement of cultural difference, a life inaccessible in both its routines and its animating beliefs, while another simultaneously invites us to leap across the centuries and identify with people who are extraordinarily like ourselves, individuals who were alive three thousand years ago, and who were capable of the same sensory responses, and pleasures, as we are.

The point, perhaps, is that both are true; that this gap between familiarity and difference is one we cannot close. A measure of translation is permanently on the agenda of cultural exchange.