The Gaia mission

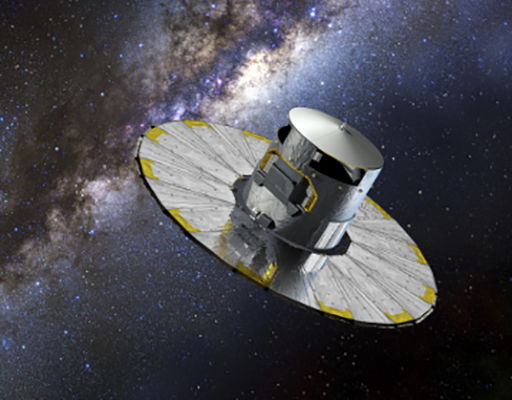

Gaia is not designed just to look for exoplanets. Instead, its task is to make the most accurate 3D star catalogue so far. This is a pretty ambitious task – and it isn’t just mapping out the precise positions of over a billion stars, it is also revisiting them many times during its mission to find out if they have moved, and by how much. It’s making an average of 40 million observations a day!

You learned in Week 3 about how we can identify the presence of planets from measuring wobbling stars using the radial velocity (RV) technique. Sometimes, if the planet is massive enough and the orbit is wide enough, it may be possible to see the tiny star movements directly – a technique called ‘astrometry’. Gaia can make astonishingly precise measurements of star positions, equivalent to measuring the width of a human hair 1000 km away! With this capability it is expected to detect tens of thousands of new Jupiter-like planets. See the European Space Agency’s webpage about astrometry [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] .

While Gaia will certainly add to the planet haul, it’s probably not going to help us in our search for an Earth twin. It’s going to be much easier for Gaia to find larger planets that make stars wobble more. For smaller worlds, we need to turn to TESS, and the future mission PLATO.

Activity 3 Exoplanet.eu website

Revisit the Exoplanet.eu website. Are there any planets that have already been found using the astrometry technique? If so, how many? (Reminder: the website is http://exoplanet.eu/; to get to the catalogue click the ‘All Catalogs’ link, select ‘Show All entries’, then use the ‘Detection’ drop-down menu.)

Answer

At least one planet has already been detected using astrometry. By the time you do this activity, there may be more. You can find the amount by changing the ‘Detection’ option to show ‘Astrometry’.

You may have noticed that some of the objects listed don’t seem to follow the exoplanet naming conventions you learned about in Week 3. In particular, upper-case rather than lower-case letters are used. These objects are so massive that they may in fact be failed stars – brown dwarfs – rather than gas giant planets. The boundary between such objects is a bit fuzzy, so the labelling convention for binary star companions has been used.