Water, water, every where,

And all the boards did shrink;

Water, water, every where,

Nor any drop to drink.

The Rhyme of the Ancient Mariner (1834 text), Samuel Taylor Coleridge

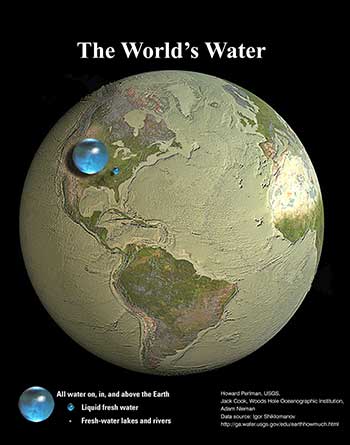

The World's water in 3 spheres

The World's water in 3 spheres

As the Ancient Mariner realised, almost all of the water on Earth is seawater. Of the total volume of water on Earth (1.4 billion km3), only 2.5% is freshwater (35 million km3).

And even most of this is ‘locked’ in glaciers and ice or underground rock. Which leaves a mere 1% of all water on Earth readily available to ecosystems in lakes, rivers and other surface water bodies. And readily available to us in our societies, our economies, our cultures, our politics and our daily lives. In a climate changing world, our collective future depends on how we manage this 1%.

The largest blue sphere is all water on, in and above the Earth, including seawater. The second smaller sphere is liquid fresh water. The almost invisible third sphere (just above the Florida panhandle) is fresh water in lakes and rivers. This approximates to the 1%.

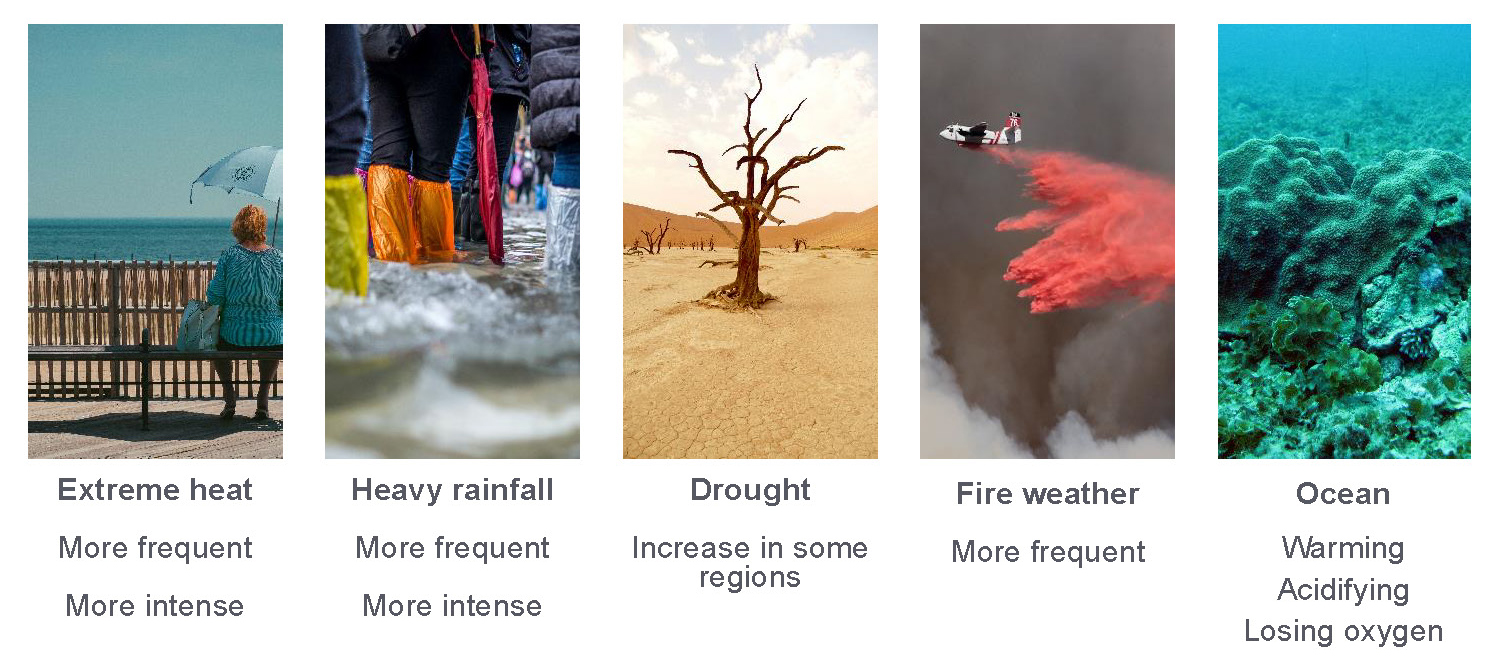

Globally, we now use 8 times more water than in 1900; an increase from 500 km3 to 4,000 km3. About 70% of this is for irrigation, about 22% for industry and about 8% for domestic use. But geographical distribution and access is very unequal. Even with stable weather patterns over the last century, some 2.4 billion people lack access to basic sanitation facilities. Around 663 million lack basic access to drinking water, particularly in sub-Sahara Africa and South Asia. Climate change will intensify these inequalities and impacts on lives and livelihoods. A report to the COP26 climate conference in Glasgow warns that a 1.5 oC increase in global temperatures will mean a heatwave that occurred only once in 50 years before human influence on the climate, is now likely to occur 8 times during the same period. Droughts that happened once every decade will now occur twice and intense rainfall events will now occur 1.5 times.

The impact of climate change relating to weather

The impact of climate change relating to weather

The western tradition of water management of meeting demand by building reservoirs and using groundwater has immeasurably improved the lives of billions. But in a climate changing world, investing to meet increasing consumption is to recognise only half the problem and solution.

Cape Town, South Africa experienced an intense drought in 2018 and teetered on ‘Day Zero’ – the complete end of the municipal water supply. This was narrowly averted by a massive city-wide campaign to reduce demand. In California, increased demand during the 20-year megadrought has seen historic lows in 2021 for Lake Oroville, supplying 27 million people in Los Angeles and Las Vegas, and the Hoover Dam supplying 120 million people. The Oroville dam also reached dangerous highs during extreme rainfall in 2017, forcing evacuation of 180,000 people downstream.

But change in understanding and managing the 1% is happening. One of the most innovative ways has been to give rivers legal status. In 2017, New Zealand recognised the Whanganui River as a legal entity after pressure from Maori leaders that the river is a ‘living whole’ rather than an extractable resource. Adrian Rurawhe, Māori member of Parliament, explained:

It's not that we've changed our worldview, but people are catching up to seeing things the way that we see them.

In 2019, the Bangladesh government granted all of its rivers the same legal status as humans, making damage to rivers a criminal offence. Water, rivers and their catchments are also increasingly being co-managed by their communities. In the Limpopo river in South Africa and Mozambique, collaborations with farmers have re-emphasised the role of water in food security, health and economic and social well-being.

A map of catchment partnerships in the UK

In Argentina, Bolivia, Paraguay, and Brazil, communities on the Pilcomayo River have collaborated to develop early flood warning systems, with knock-on positive changes in women’s roles and access to education.

A map of catchment partnerships in the UK

In Argentina, Bolivia, Paraguay, and Brazil, communities on the Pilcomayo River have collaborated to develop early flood warning systems, with knock-on positive changes in women’s roles and access to education.

My own research and teaching have developed systems thinking and collaborative or social learning approaches to water management. Systems thinking acknowledges the holistic nature of water and our own roles and collaborative responsibilities as managers in water systems, rather than just as consumers. In England, this approach has helped develop catchment partnerships between government and national and local groups. From very small beginnings, the partnerships are now working in every locality to improve rivers and their catchments.

These new initiatives recognise that water is essential to all life on Earth, not just for human use. A changing climate means we need to be collaborative, creative, adaptive and caring in how we manage the 1% for humans and biodiversity to thrive.

Click on the banner to explore the COP26 hub

Click on the banner to explore the COP26 hub

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews