Repairing or updating products to extend its lifespan

Repairing or updating products to extend its lifespan

You may be asking what has product repair got to do with action to mitigate against a warming planet? Every new product produced, distributed, used and disposed of contributes to environmental impacts, including the production of carbon dioxide and other climate warming gases. Producing less products and using existing products differently and for longer, will reduce lifecycle emissions and impacts.

Globally we generate approximately 40 million tons of electronic waste (e-waste) each year of which only 12.5% is recycled. That’s a lot of valuable resources being mined, produced and displaced, with resultant toxic substances such as mercury, cadmium and chromium polluting air, soil and water systems. These figures illustrate significant impacts from a consumer electronics sector that is growing by about 8% each year as new markets expand and demand for replacement products, such as phones, rise (theworldcounts, 2021).

An assortment of well-worn tools

A response to this cycle of production, use and disposal is to produce less stuff and make things last longer. Thrift, frugality, ‘make do and mend’ are words and phrases associated with a lifestyle necessitated through crises, invoked - in the UK anyway - by the experiences of living through WWII. I remember my gran coming to live with us when I was 12 years old, bringing with her the practices of make do and mend. She darned our socks – caring and repairing for clothing items, now deemed disposable. Our then neighbour, a retired engineer in his 80s, carefully maintained his work tools, accompanied by boxes of nails and screws of all shapes and sizes just in case they were ever needed.

An assortment of well-worn tools

A response to this cycle of production, use and disposal is to produce less stuff and make things last longer. Thrift, frugality, ‘make do and mend’ are words and phrases associated with a lifestyle necessitated through crises, invoked - in the UK anyway - by the experiences of living through WWII. I remember my gran coming to live with us when I was 12 years old, bringing with her the practices of make do and mend. She darned our socks – caring and repairing for clothing items, now deemed disposable. Our then neighbour, a retired engineer in his 80s, carefully maintained his work tools, accompanied by boxes of nails and screws of all shapes and sizes just in case they were ever needed.

These memories are remnants of a recent time when, in everyday life, we had the capability to re-jig, alter, mend, maintain the material world that flowed through our homes. And just as this was once commonplace for whole generations of folk, those practices have gradually disappeared, and with them the knowledge and skills that were once familiar, now forgotten by generations growing up in a technological, information-based world. Today, ideas of repair are not about looking back nostalgically on times where necessity required extreme resourcefulness, but given the multiple current crises of economy, health and climate, it is perhaps useful to consider how we can develop capabilities for the care of our material world and provide new opportunities to decarbonise our product environment through better design and different practices of use.

In the last fifty or so years we have seen huge advancements in technology and yet product lifespans, in many cases, have decreased in length. We are not surprised today if the toaster or kettle only lasts 2 or 3 years. Perhaps we should be. Perhaps we should expect more. A fast turnaround of products adds to the linear flow of resources, much of which ends up in landfill or incineration.

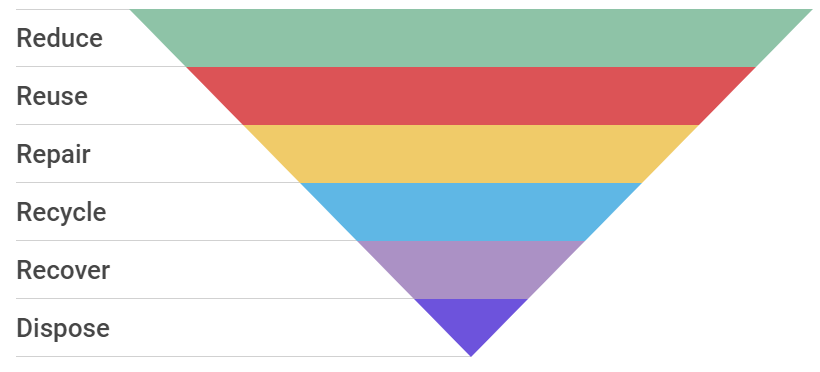

Increasing product lifetime and increasing its utility, are strategies that encourage greater resourcefulness. Waste management begins with prevention and ends with disposal, with many steps in between. You may recognise the Reduce, Reuse, Recycle hierarchy. If we can prevent and reduce e-waste at its current levels, then we can deliver impactful reductions in the carbon emissions of products.

A revised waste hierarchy with a focus on reducing the generation of waste.

A revised waste hierarchy with a focus on reducing the generation of waste.

We know that it is generally better for products to last for extended periods of time. Traditionally when you had a product with a mix of slow and fast technology, it was felt that the fast-moving technology should be replaced more often to provide a better overall environmental performance in use. An example being the increasing energy efficiency of refrigerators and washing machines. However, in recent years that gain in efficiencies has plateaued and it is no longer the case that energy consuming products should always be replaced by slightly more efficient ones. In fact, it would be quite useful, in environmental terms, if products could last much longer: for example, a washing machine that lasts for 20 years (Bakker et al, 2014). Design strategies that enable good care and maintenance, facilitate repair and create opportunities for servicing and life extension are all part of resourceful thinking focused on the prevention of waste.

Reducing the environmental impact of product also relies on new behaviours and practices of use. There is not much point in creating a mobile phone that could last ten years if people expect a new phone in 2 years. Product information that displays ‘invisible’ environmental impacts or that links to carbon emissions, may help many understand the whole impact of product lifecycles and the different habits of use that are also required to extend product lives.

As part of our ongoing design for sustainability research and teaching, we are interested in understanding the difference between actual and expected product lifetimes and what might encourage greater levels of product repair. We would like to encourage learners to respond to this short survey by clicking the link and answering a few questions based on your own product and repair experiences. Thank you.

Product Life & Repair Survey (using surveymonkey)

Click on the banner to explore the COP26 hub

Click on the banner to explore the COP26 hub

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews