4.2.2 Institutional hygiene and healthcare-associated infections (HCAIs)

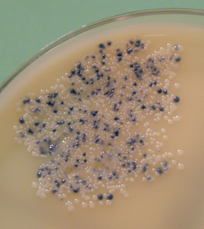

In the first five years of the twenty-first century, the news media in the UK reported increasing alarm over rising numbers of cases of two bacterial infections believed to have been acquired by patients in hospitals, nursing and residential care homes and rehabilitation centres. The conditions are methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) (Figure 12), which is resistant to the antibiotic methicillin, and ‘C.diff’ or Clostridium difficile infection (CDI). (Note that the antibiotic generally referred to as ‘meticillin’ in the UK, is known as ‘methicillin’ in most other parts of the world.)

MRSA and CDI are not the only healthcare-associated infections (HCAIs), but they are responsible for the most serious, sometimes fatal, cases in the UK. Often overlooked in media reports of HCAIs is the increasing transmission of methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) and some other pathogens.

Why are staphylococcal infections a significant problem in healthcare settings, particularly in surgical wounds?

Staphylococci are normal commensal bacteria found in the upper respiratory tract, on the skin and the lining of the large intestine and vagina. Although they are endogenous on these external surfaces, they are easily transferred into wounds, where they cause tissue-damaging infections.

C. difficile is also found naturally in the large intestine, but only in about 3% of adults in the UK, where it is normally kept in check by competition with commensal gut bacteria. However, C. difficile can ‘overgrow’ in elderly or frail patients who are taking broad-spectrum antibiotics, which destroy competing bacterial species. It is easily spread as spores, which may be hard to eradicate from healthcare institutions where susceptible patients are most at risk of becoming infected. CDI results in severe ulceration of the large intestine (a condition known as pseudomembranous colitis), with painful, copious diarrhoea (NHS Choices, 2012).

The blame for outbreaks of HCAIs is attributed to poor institutional hygiene, including inadequate hand washing by staff in contact with patients. A vigorous campaign to reduce the transmission of HCAIs was initiated in UK hospitals and other healthcare institutions in the late 1990s, and has had significant success. But these infections still cost the NHS an estimated £1 billion per year, in addition to the pain and suffering of patients who acquire an HCAI (DH, 2012).

Surveillance

Surveillance has played a key role in tackling the problems posed by HCAIs.

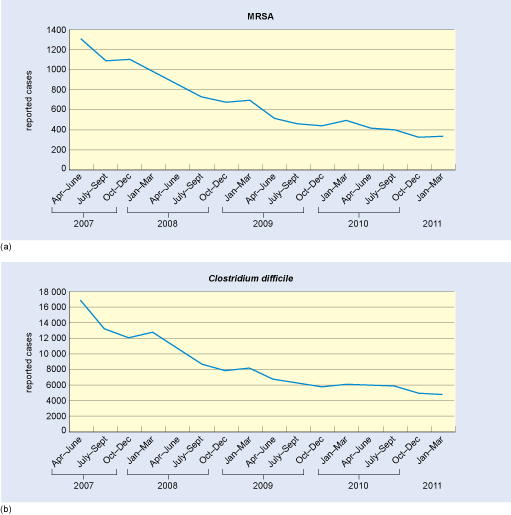

Mandatory surveillance in England began in 2001 for MRSA and in 2005 for CDI, and all cases in English NHS hospitals have been reported to the Health Protection Agency since April 2007 via a web-based Surveillance Data Sheet. So-called ‘lab returns’ on the number of positive blood cultures (MRSA bacteraemia), and CDI-infected stool samples, are collected from each location.

Patients are now routinely screened for nasal carriage of MRSA before and at admission to NHS hospitals, and all stool samples received from people aged over 65 years with diarrhoea are tested for CDI, including samples sent in by general practitioners or GPs (family doctors in the UK).

Strict surveillance has enabled outbreaks of HCAIs to be tackled quickly by isolating patients, initiating ‘deep cleaning’ regimes of wards and equipment, and installing numerous alcohol-based hand-rub dispensers for use by staff and visitors (Figure 13).

Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) service

Every NHS hospital now has an Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) service responsible for the prevention, surveillance, investigation and control of infection. This is achieved through mandatory education and the development and implementation of effective policies and procedures. Data on the rates of MRSA and CDI cases and the standards achieved by the IPC service are regularly reviewed by quality standards bodies in the four UK nations, for example the Care Quality Commission (CQC) in England.

Patients and staff are interviewed on their assessment of cleanliness in the environment, staff hygiene and on the availability of the equipment and services necessary to achieve the prevention and control of infections. If there is a cause for concern, the CQC makes unannounced inspections to ensure that appropriate guidelines are in place and being observed by staff.

Figure 14 illustrates the steady success in reducing the rates of MRSA and CDI in recent years, through the systematic application of two traditional public health measures – hygiene and surveillance.