Building shapes and climate

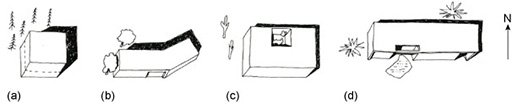

It is nevertheless possible to consider the overall shape of a building and its orientation on an idealised open site and to reach conclusions about the best design that is suited to a particular climate. There are four principal types of climate: cold, temperate, hot-arid and hot-humid that lead to different forms of building (Figure 5).

In cold regions the need to conserve heat is very important and leads to trying to minimise the outer surface area of the home, in order to reduce heat loss. This minimum surface area is achieved, for example, in the hemispherical (half-sphere) form of the igloo.

In temperate regions (such as the UK) a rectangular plan is desirable, with the shorter sides facing east and west. Such a home has a long southern face, which catches the Sun when it is available. Because the climate is not so extreme in temperate regions, however, more diversity in home shapes is possible in without significantly affecting heat gain or loss.

In hot-arid (desert) regions the extreme conditions demand a return to a more compact shape, with the addition of special features such as internal, shaded courtyards cooled by water to help create a comfortable ‘micro-climate’ within the home and its immediate surroundings.

In hot-humid (tropical forest and swamp) regions the actual temperature is usually not so excessive as in hot-arid regions, but the high humidity significantly affects discomfort. So long as the roof provides adequate shelter against rain and Sun, an open-sided elongated shape has the advantage of being able to catch any cooling breezes.

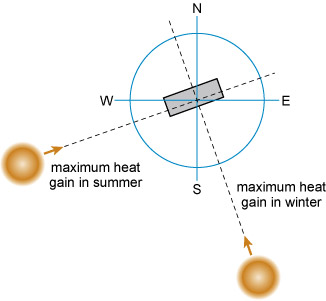

The orientation of the home is obviously important for elongated shapes. Usually the dominant factor is the orientation of the main facade towards the Sun, though other factors (for example, wind direction and ease of access) can be just as, or more, important in planning the orientation of the home. In temperate regions this is a matter of trying to arrange the home shape and orientation so as to collect as much heat as possible from the Sun in winter, while avoiding overheating from solar gain in the summer. In temperate regions in the northern hemisphere the maximum summer solar gain in fact comes from a south-westerly direction, whereas the maximum winter solar gain comes from slightly east of south. These comments apply to the whole home, not just to window orientation, and to the build-up of heat during the whole day. This conveniently means that, in northern temperate regions, the optimum orientation for the longer facade is just to the east of south so as to receive the most winter warmth, thereby turning the shorter facade to the south-west, the direction of highest solar gain in summer (Figure 6).