Is there a Peace Dividend?

The Northern Ireland Economy can be described as a curate’s egg: good in parts, but the impacts of the Troubles have worsened the trajectory what can be called a hybrid economy. That is, some of the path dependent weaknesses of the economy (productivity difficulties, skills and training deficiencies) have continued in spite of benefits of greater peace over the last 25 years.

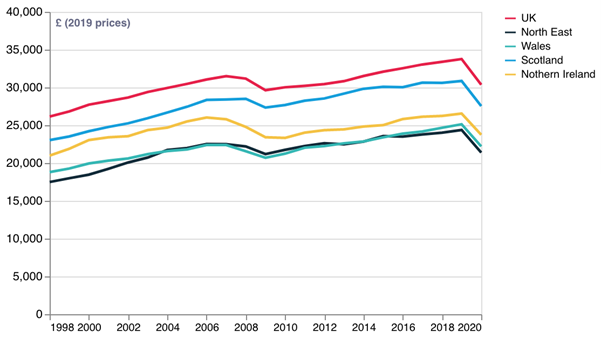

The Troubles are estimated to have reduced Northern Ireland’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) by up to 10%. GDP per capita that was 20% lower than the overall UK level in 1998, but higher than either Wales or the North East of England. The term peace dividend has several meanings and contextual connotations. For some writers, it represents a revival in aggregate output following the cessation of conflict during a civil war, as for Northern Ireland. The Global Peace Index has estimated a positive multiplier of 1.49 for every single reduction in its conflict index measured on a scale from 1 to 5.

In the case of Northern Ireland, there are myriad reports and academic papers examining this question and in one case of the impact of a peace dividend on tourism and investment and house prices, respectively, positive effects are found. However, the arguments that the weakness of the NI economy is driven by a bloated public sector since the GFA do not stand up to scrutiny. Rather a successively weak private sector and a historical legacy of large staple industries seems a better explanation. Figure 1 below displays the relative performance of Gross National Product (GDP) per head in Northern Ireland since 1998.

What appears to be common to all conflicts is that economic inequality is a major driver of setting one community against another, and sadly this remains a legacy for Northern Ireland. In looking to potentially emulate the performance of wealthier regions.

Figure 2: Relative real GDP per capita (2019 prices)

Source: Office for National Statistics (ONS), 2022; regional gross domestic product, all ITL

regions

Northern Ireland carries an economic legacy of conflict that no other devolved nation or region in the UK has had to endure.

Hybridity and Path Dependency

There have been three main interpretations of the challenges facing the contemporary NI economy:

- ‘The silver bullet’ or ‘game changer’ interpretation that looks to imitating certain parts of the Irish Celtic Tiger model.

- The weaknesses of the NI economy as being a failure to invest in capital of both physical and human form with deficiencies in education that explain low productivity.

- The NI economy being locked in a kind of underdevelopment trap that is an important element in explaining the persistence of weak economic performance linked to productivity.

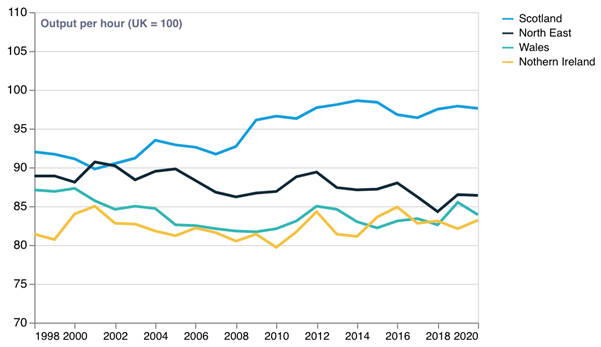

Figure 2 shows the continuing productivity challenge since the GFA in relation to the rest of UK.

Figure 2: Productivity, output per hour (UK=100)

Source: ONS, 2022; regional productivity time series

On the brighter side, employment growth since the GFA has been the highest outside London and wages for the lowest paid has improved relative to the rest of the UK, but economic inactivity remains high.

The combination of Brexit and the Covid-19 pandemic represent a place-based shock to the economy. In the case the former, the Windsor Framework of the Northern Ireland Protocol (NIP) has been preserved the special position of NI within the UK to some degree. Consequently, there are several possibilities for some sectors to take advantage and break out underdevelopment traps.

Revitalising the NI Economy?

In the last decade or so there have been a number of economic and industrial strategies aimed at contributing to revitalising the economy. There has been a focus on what are called the MATRIX priority sectors:

- Agrifood Technology;

- Sustainable Energy;

- Information & Communications Technologies (ICT);

- Life & Health Sciences;

- Advanced Manufacturing & Materials

There has also been recent growth in sectors like Fintech, tradable advanced business services, cybersecurity, film and television and consulting services. The danger is that key sectors like Agrifood and tourism become disconnected from these high-value sectors. Both are closely related to all-Ireland markets and beyond. Agri-food sector’s importance to the NI economy goes beyond is nominal size in that it is not only a large employer, but it is part of a key Global Value Chain (GVC) within an All-Ireland market that’s cuts across Great Britain and international markets. It is currently one of the few sectors to benefit from “the best of both worlds” of the NIP. Irish agriculture has been in the forefront of sustainability for time now and connects to tradeable business and consulting services.

In the case of tourism, the peace dividend since GFA has stimulated growth and made NI an increasingly important visitor economy. Revenues peaked at £1bn in 2019 but like many places has been hit by the pandemic. There is now a Tourism Recovery Plan in place and given the growth of NI as a destination for the Game of Thrones film franchise, the growth of local film services also contributes to the revival of the tourist sector.

Connecting the Peace and Devolution Dividends

The direct economic benefits of the peace dividend have been variable but not large. It has, however, brought significant externalities for NI. A key issue is that of governance and in particular devolution. The concept of an ‘economic dividend’ has been used to encompass the benefits of devolution. The principal outcomes are identified as generating allocative and productive efficiencies, alongside the accountability and participation benefits of devolution for decision-making and co-ordinating collective policy action. The important point is that the devolving of powers tends to be create a more coherent framework for regionalised economic policy making by incorporating key local agencies and stakeholders into decision-making structures and processes. Consequently, forms of institutional and partnership decentralisation lower the transactions costs of policy making. A similar argument applies to fiscal decentralisation in respect of targeted expenditures and embedded taxes.

The problem for NI is that since the Assembly’s inauguration in 1999, it has been without a government for nearly nine of the past 23 years. Most recently, the Assembly was suspended for two periods to the present day. These are recent examples of how poor governance has plagued NI since 1998. The negative impact of poor governance has now been recognised, however, accompanied by a better diagnosis of challenges that feed into more effective public policy prescription and implementation. Devolution also provides a platform for addressing localised inequalities of wealth and income as well as contributing to levelling up poor places. But, if the promise of revitalising the NI economy is to occur 25 years after the GFA, the economic dividend of devolution will have to be grasped again in combination with increasing the peace dividend to the benefit of all Northern Ireland citizens.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews