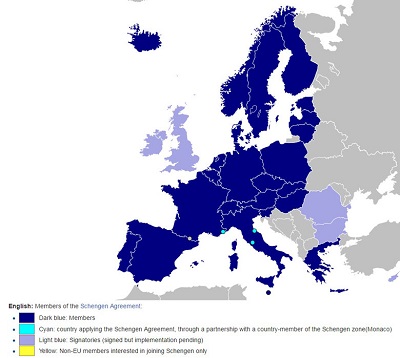

Borders are supposed to be at the edges of sovereign territory, a place where access and entry is controlled through checkpoints and passport controls. In the case of the European Union, responsibility for policing its external borders lies with FRONTEX, a European-wide agency that exists to secure the EU’s borders from illegal migrants, smugglers and terrorist threats. Security, one of the key themes of the OU interdisciplinary module International development: making sense of a changing world, lies behind the notion of ‘Fortress Europe’ – an outside closed off from external threats and an inside of border-free travel and movement.

Borders are supposed to be at the edges of sovereign territory, a place where access and entry is controlled through checkpoints and passport controls. In the case of the European Union, responsibility for policing its external borders lies with FRONTEX, a European-wide agency that exists to secure the EU’s borders from illegal migrants, smugglers and terrorist threats. Security, one of the key themes of the OU interdisciplinary module International development: making sense of a changing world, lies behind the notion of ‘Fortress Europe’ – an outside closed off from external threats and an inside of border-free travel and movement.

Or, at least that was the case, until the fences and walls started to go up on the inside of Europe.

The future of Europe’s passport-free, Schengen zone is in doubt now that a number of its member states, one after the other, have established border controls in the face of an unprecedented surge in migration and those seeking asylum. Add into that mix the recent terror attacks in places like Paris, and the predictable fear and insecurity generated has produced a domino-like territorial effect, with border fences and high walls erected from the top to the very bottom of Europe.

The plugging of borders started in central and southern Europe, with Bulgaria closing themselves off from Turkey in 2014, Hungary doing the same to Serbia in the middle of 2015, followed by Macedonia threatening to do likewise to Greece. Then the process moved north, with Austria erecting a barbed wire fence between themselves and Slovenia, Germany reimposing border controls, and Sweden, in a reversal of its political immigration stance, introducing border checks on the Oresund Bridge that links it to Denmark. The latest move (at the time of writing) is the EU’s threat to quarantine Greece by suspending it from the Schengen travel zone.

The political effect of such barriers is by and large symbolic, aimed more at reassuring domestic audiences than actually plugging security or halting the flow of migrants. But they do achieve one thing: they make it difficult for people to reach, not Europe’s shores, but its affluent core.

On the outside looking in

Strictly speaking, the introduction of border controls by EU member states should have no bearing on those crossing borders to seek asylum. Under the 1951 Refugee Convention, set up in response to the tragedy of the Holocaust, member states have an obligation to assess all asylum claims on their territory. Anyone seeking asylum is entitled to do so under international law. But there’s a catch: you first have to reach a member’s territory in order to claim it. You have to be on the ‘inside’ looking out, not on the ‘outside’ looking in. Walls and fences, checkpoints and border controls, are erected for a reason: they place people on the ‘outside’.

As such, there seems to be a clear political logic at work. With EU member states unwilling to be the one that gets ‘stuck’ with migrants on their territory, the drive is for Europe’s borders to be pushed further outwards. Rather than risk a ‘limbo’ situation where migrants become trapped in the frontline states of Greece, Bulgaria, Italy and Spain, or worse, further inland, better to shift the line between inside and outside by preventing access to Europe in the first place.

Is there another way to interpret plans for a new EU border guard to tackle people-smuggling networks or the establishment of what looks to be holding camps outside of Europe? Last year’s agreement with Turkey to swop visa-free travel in the EU in exchange for limiting the numbers reaching Europe’s coastline would appear to be such a shift. Not that there is anything particularly new about it, with the precedent of detention centres in Libya having been established over a decade ago to prevent the flow of migrants to Europe from sub-Saharan Africa.

If you can keep people firmly on the ‘outside’, they can be denied access to rights that they would have if present on the ‘inside’.

Open or closed Europe?

With the outsourcing of EU border controls and member states taking back control of their own borders, the overarching impression is of a territory closing in on itself, restricting the right of movement and blocking access. But that’s really only half the story.

The OU geography module DD205 Living in a Globalised World teaches us that territory and flow are two sides of the same coin; that borders connect as well as divide. Even at the height of Hungary’s determination to close its borders to the flow of oncoming migrants, it vigorously defended the right of free movement across Europe. The contradiction is more apparent than real, for in the political thinking of member states Europe remains ‘open’ – but only for the ‘right’ kind of people.

Territorial borders, after all, have never just been about keeping things out. They are as much about inclusion as exclusion, more a filtering mechanism to sort out ‘wanted’ from ‘unwanted’ migrants, the ‘safe’ from the more ‘risky’ population. Of late, the technical ability to screen, profile and filter the movements of people has advanced greatly. ‘Smart borders’ are the coming thing, risk-management technologies that rely on biometrics and data-tracking to fast track entry for leisure and business elites and block access to those deemed a security risk or the ‘wrong’ kind of migrant.

In writing about the borders of Europe, Etienne Balibar, a French political philosopher, asserted that “borders are no longer the shores of the political but have indeed become… things within the space of the political itself”. By this, I take him to mean that borders are no longer the simple territorial limits of sovereign power that they once were. More than a marker of sovereign territory, Europe’s multiple borders today arguably reflect the contingent politics of partition and division, where borders move in and out in concertina-fashion to the tune of geopolitics - with asylum seekers stranded when the music stops.

Want to listen to this article?

John Allen talks through these ideas in the following audio:

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews