Economic growth in the global South has begun to dominate world imagination. Ever since a series of reports produced by Goldman Sachs in the 2000s suggested that countries like China, India, Brazil, Russia and South Africa were driving economic growth, there has been increasing interest in the Rising Powers, as they have come to be called. They have proven to be the major drivers for raw material extraction as well as key producers and consumers of goods. Moreover, this growth has also catalysed more widespread economic developments in the global South and the North. Along with the financial slowdown in Europe and the US, the growth of the Rising Powers has led to a rebalancing of the global economy.

The Rising Powers have each had different bases for their ‘rising’ as well as varied trajectories of growth. Chinese economic growth has been powered by manufacturing while India’s growth has, at least in part, been attributed to the growth in services, most notably in the Information and Technology sector.

Chinese manufacturing has been underpinned by the labour of rural men and women who have moved to cities. The importance of women in manufacturing and the growth of nations was commented on in the 1980s when the so-called Asian Tigers – Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore and South Korea – experienced significant economic growth underpinned by manufacturing. Some scholars attributed the heavy presence of women in factories to their nimble fingers, but far more significant was the fact that women were paid less than men, were less likely to unionise and were therefore cheaper and more easily disposable labour.

This tradition of using women in manufacturing continues to power economic growth globally. In the tragic events surrounding the collapse of Rana Plaza complex in Bangladesh, due to structural faults in the building, it was reported that more than half of those who died were women.

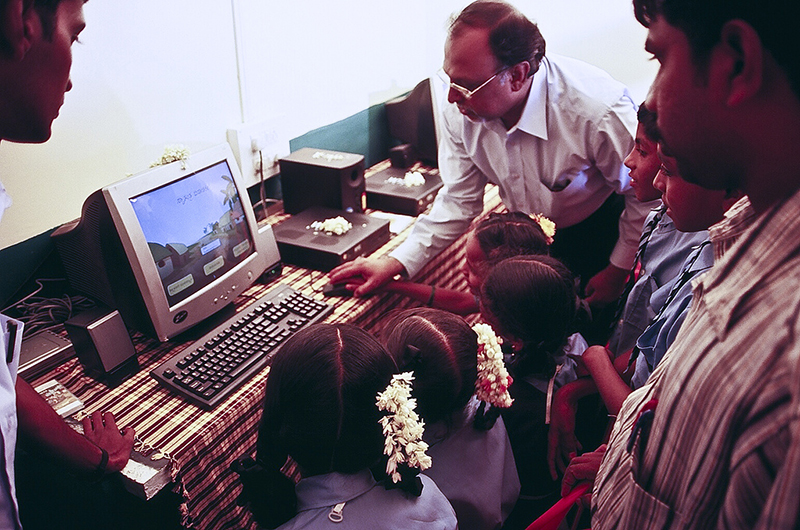

Gender, IT and economic growth

More surprising, however, is the presence of women in India’s service-led growth. Why? Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics are increasingly seen as vehicles for growth in the new knowledge economies. Yet there are very few and often falling numbers of women taking up these subjects in the Western Europe and the US. This feeds through into the labour force too, with small and falling numbers of women especially in the highly skilled sector of Information Technology. This sector is seen as crucial for powering future economic growth but it is one area where this gender discrepancy is particularly stark. Women only constitute 11% of IT specialists in the IT industry in the UK. Once in work, women also leave the industry in larger numbers than men.

Yet in India, the IT sector seems to be more gender equitable. Female enrolments in science and engineering education (around 65%) and IT labour force participation (around 30%) are considerably higher in India than in the UK – in fact, they are amongst the highest of the countries studied in an OECD survey (Salvi del Pero and Bytchkova 2013). Importantly, IT is seen in India as offering a more gender equitable workplace (Mitter 2000) and women are acknowledged as producers of India’s global success in IT (Radhakrishnan 2008).

So, why are there more women in IT in India than in much of the global North? There are no clear answers yet, but the video below shows us how that difference in gendered work is experienced by migrant women and men in the IT sector in the UK, and also what our new OU research project aims to do about it.

What is certain is that gender matters in the IT sector, albeit less, or at least differently, in India. Moreover, overarching trends which are captured by terms such as Rising Powers are ultimately based on gender differentiated labour.

If you work in the IT sector, or you know someone who does, and you’ve got some insight into how and why its workforce is gendered, why not post a comment?

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews